You could have been forgiven for thinking it was a church service Sunday last week. The evening opened with words from the first few verses of the Gospel of John chapter one being projected on a large screen and read out by an actress: In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God.…

Next, the speaker was introduced by his host, the director of the secular debating centre in Amsterdam de Balie, who confessed that his guest’s recently published book, Dominion, had so transfixed him while on a recent ski-vacation that only after reading the last word did he go skiing.

When eventually British author Tom Holland took the stage, he explained that the subtitle of the book’s English edition – ‘the making of the western mind’ – was the choice of his nervous, atheistic publisher afraid of scaring off readers with symbols or mentions of Christianity on the cover. Yet, in fact, he explained, the book was about the making of Christendom and how Christianity had made our society. For its coming, incubation, emergence and evolution into the world of classical antiquity was certainly the most decisively revolutionary movement in European history. And possibly globally as well.

If the modern west was a goldfish bowl and we were the goldfish, he analogised, then the waters we were swimming in were Christian. Or, he illustrated further, just as the invisible radiation from the Chernobyl disaster spread across a wide area influencing the whole environment, so too the influence of Christianity had been all-pervasive yet invisible to most.

Story teller

Jesus had to rank as the most influential teller of short stories that had ever existed, Holland asserted. The power of his simple narratives continued to reverberate into the present. The story of the Good Samaritan, perhaps one of his most influential, was about our responsibility to care for people who may be very different from us. Angela Merkel’s openness to refugees was surely shaped by her being raised in a parsonage, exposing her to Bible stories and morals. Yet, continued Holland, Viktor Orban also drew on the biblical heritage to cast his people as surrounded by enemies, leading to very different conclusions and results.

The idea of light shining in the darkness, from John 1:5, drawing from the words of Isaiah 9:2, about the people who walked in darkness having seen a great light, had profoundly shaped western thinking. From the English missionary Boniface bringing the light of Christ to those in Saxony living in superstition, to the Reformation when Rome was seen as embodying darkness and superstition, and further to the Enlightenment which condemned Christianity itself, the very image of light was drawn from Christianity. It was almost impossible to escape this legacy and to stand outside of it, argued Holland.

As a child, the author had been fascinated by the glitter and swagger of the Roman empire. He was sad that a load of monks had turned up to ruin it. The sun then as it were disappeared behind a dark cloud, he thought, and the dark ages reigned until the Enlightenment came. He confesses having totally bought into this narrative that the Enlightenment rescued the glories of Rome. Yet in writing about Rome in his book Rubicon, he came to realise how cruel and callous Caesar and his fellows Romans actually were towards humanity, boasting about how many enemies they had killed or enslaved. Researching also the Greeks, the Persians and the Arabs made him realise how revolutionary Christianity was, how it rewired the human brain with radically different moral and ethical assumptions about human nature which we take for granted today.

Stumbling block

For the key story in the Christian narrative was the Passion, the story of the cross, a public humiliation in a society where dignity was of the essence. Christianity turned the cross, a cruel Roman symbol of imperial power, into a symbol of the triumph of the weak and powerless, and the triumph of Christ over the powers of this world. Cosmic power was inverted. Paul was the earliest to write about the God of Israel, creator of the universe, being crucified, a stumbling block to the Jews and madness to the gentiles.

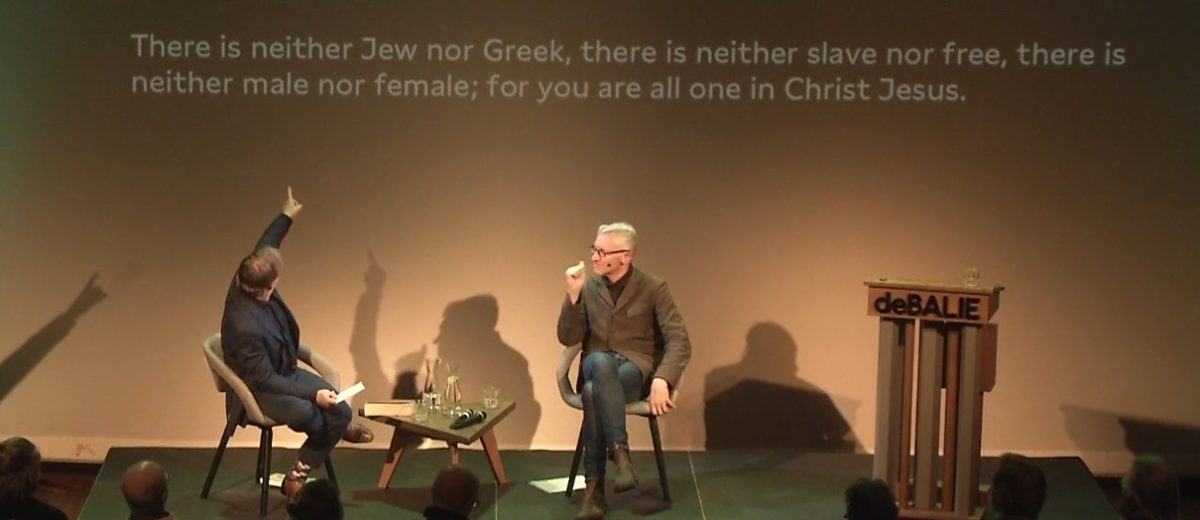

Holland came to see Paul’s letters as the most influential ever written, like acorns resulting in forests of oaks. Galatians 3:28, shown in the photo above, for example, became the source of the fundamental moral principle of equality on which western civilisation was built.

Even if Jesus had never existed, concluded Holland, he would remain the most amazing fictional character the world has known!

Watch the whole session here (with friends) and catch my question at the end about what advice he would give to Europe’s leaders today in the light of this inescapable legacy.

Till next week,