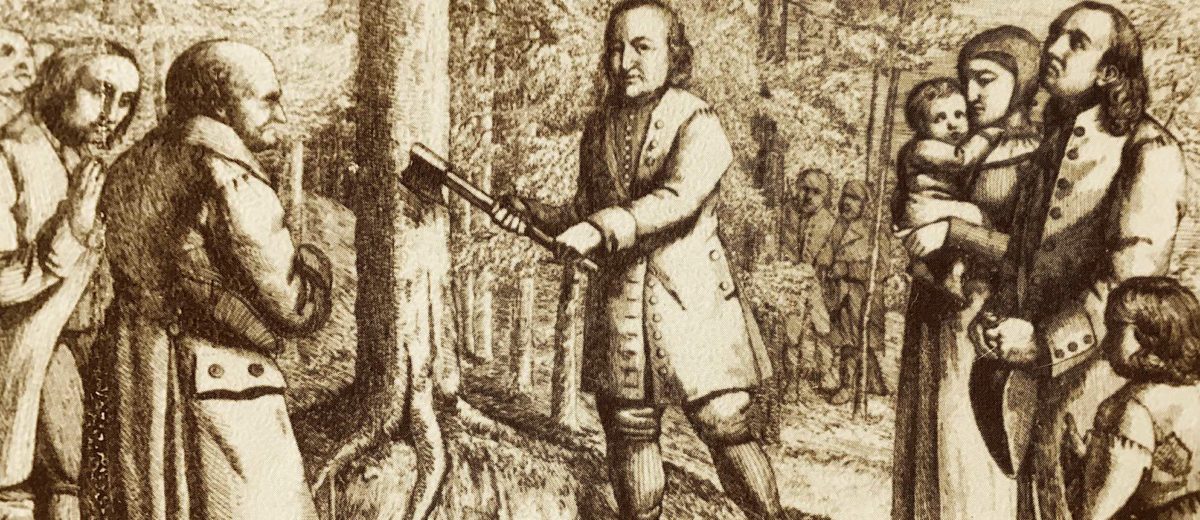

On June 17 in 1722, a Bohemian refugee named Christian David felled the first tree to start building a village that would become known as Herrnhut. David had led a bunch of fugitives from their home country across the border from German Saxony in search of safety from religious persecution. Since the Thirty Years’ War, the spiritual offspring of the fifteenth century reformer Jan Hus had been forced to go underground, convert to Catholicism, lose their lives or flee the country.

It was the first act in establishing a remarkable town where descendents of these refugees still live, nestled close to the Polish and Czech borders, the story of which I have told in a small book, The little town that blessed the world. For the road to world missions passed right through this town. The Herrnhutters, or Moravians, were pioneers of Protestant missions, sending out several hundred missionaries to places as remote and difficult as the Caribbean, Greenland and Africa, long before William Carey–often called the father of modern protestant missions–left for India in 1793.

John Wesley’s conversion was midwifed by members of this village, passing through London en route to mission work among the Indians in Georgia. What would England have looked like if not impacted by the Wesleyan revival of the eighteenth century, and all the social transformation that the Methodist Revolution brought to the country that was leading the world into the Industrial Revolution at the time?

Ordinary

No one passing by on the road through the woods that particular day, as David laid the axe to the tree, would have recognised a first step in a development of global significance. Zechariah saw the beginning of Zerubbabel’s work in building the temple, and heard the Lord say: “Do not despise these small beginnings, for the Lord rejoices to see the work begin, to see the plumb line in Zerubbabel’s hand.” Or to see the axe in Christian David’s hand. How ordinary! Yet how significant!

For Zechariah also heard the Lord say, “It is not by might nor by power, but by my Spirit” (Zech 4:6,10).

For us in the Schuman Centre, June 17 this week marks a significant day, a day of small beginnings. For today the first intake of students for the master’s programme in Missional Leadership and European Studies began, a project Weekly Word readers who responded to our appeal early last year have helped to make happen. For which we are very grateful.

Since we started the Schuman Centre for European Studies in 2010, we have been looking for ways to interface our training with recognised institutions so that the legacy can be preserved. Today’s milestone represents the first university degree programme partnered by YWAM (that I know of) that will be recognised under the Bologna Process, a European-wide arrangement involving 48 nations aiming to unify standards and quality of higher-education qualifications.

The degree is offered by ForMission College in Birmingham, UK, validated by Newman University, also in Birmingham. The Schuman Centre facilitates three modules on European studies to supplement three other modules in missional leadership students must complete, along with a dissertation.

All-pervasive

Over the past two months, as I have been writing the study manuals for the first module on ‘the making of Europe’, I have been freshly overawed by the remarkable role of the Bible in the transformation of both the ‘civilised’ south and the ‘barbarian’ north; in the emergence of monastic communities—the building blocks of the emerging society after Rome’s collapse—leading to the cities and universities of the late Middle Ages; in catalysing the Renaissance and of course the Reformation; and in stirring the revivals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Even the so-called secular era, starting with the French Revolution, could not escape the all-pervasive influence of the Judeo-Christian sacred writings as political options emerged to champion liberty (liberalism), equality (socialism) or brotherhood (nationalism), developing into political religions with their own messages of salvation from social evils.

The Bible of course has also been misused by (pseudo-)Christians of all stripes and colours throughout the centuries, not least in the twentieth century, as Philip Jenkins reveals in his ground-breaking treatment of the religious motivation of the warring parties in what he calls ‘The Great and Holy War’.

Yet at no stage of Europe’s history does the Bible not play a critical role. Behind the emergence of the European project after the Second World War, and the implosion of communism forty years later when secularism supposedly reigned, the Bible’s restorative role is clearly tangible.

Recovering this story is what this programme is about. Small beginnings perhaps. Like a plumbline. Or an axe.

Till next week,