The 19th in a series of draft chapters for a popular-style illustrated coffee-table book about how the Bible has shaped so many facets of our western lives. Feedback is welcomed.

COMPASSION AND DEVELOPMENT

Non-governmental organisations have become major global players alongside the governmental and business sectors. Today there are several million NGOs globally, recognised as key third sector actors in fields of humanitarian aid, environment, human rights, migration, refugees, trafficking, peace-building, relief and development.

UN sources report some NGOs to have budgets exceeding those of some Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) donor countries: such as, World Vision (€2.5 billion), Save the Children (€1.23 billion), Oxfam and Médecins Sans Frontières (both around €1.1 billion) and Catholic Relief Services (€720 million) [2011 figures].

What influence can we trace of the Bible in both the creation and the motivation of such organisations? Both secular and religious NGOs are moral entities, challenging unjust and inequitable situations. Religious NGOs openly recognise their obligation towards the divine and to humans created in God’s image.

Secular agencies generally aim to promote human rights. As we have argued previously, while the concept of human rights is often assumed to be non-religious, what basis is there for recognising the dignity and sanctity of human life, from which human rights are derived, without the biblical understanding of humans as reflecting God’s image?

While other non-profit organisations like universities, sports clubs and trade unions exist for the interests of their members, NGOs are values-based, existing to serve others: the underprivileged, the needy, the neglected and the deprived. Although most secular and non-Christian religious NGOs only emerged in recent decades, works of compassion have a centuries-long history in the Christian tradition.

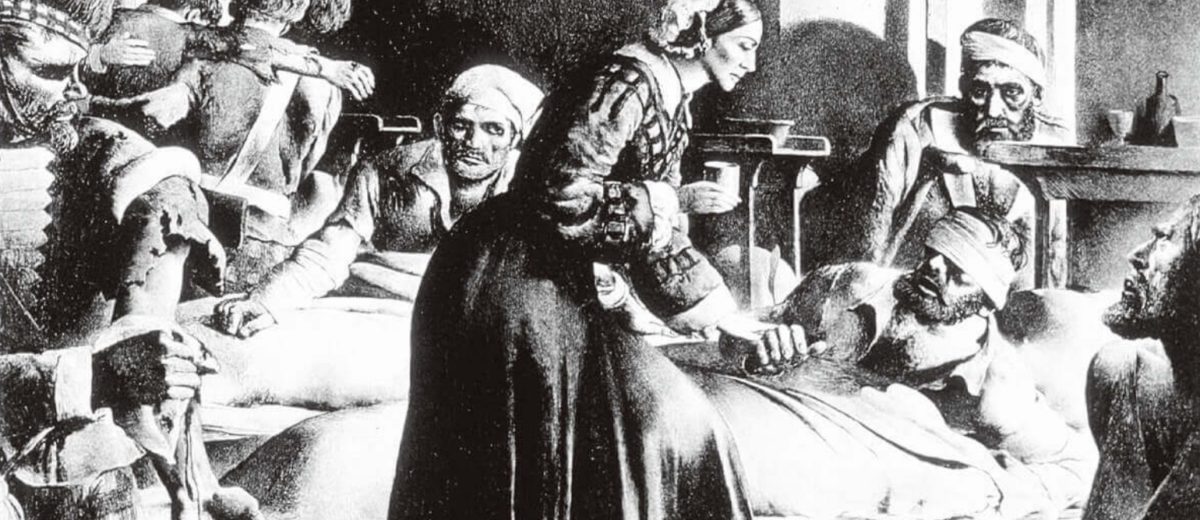

Throughout the Middle Ages, monasteries and orders often specialised in various types of ministry to the poor, disadvantaged, abused, sick and imprisoned. Examples of saints like St Martin and St Francis, often depicted in stained-glass windows, reminded clergy and laity alike of the six works of mercy (Matthew 25) – to the hungry, thirsty, sick, homeless, prisoners and naked – and that the sheep and goats would be separated on the basis of such acts of compassion.

In Reformation countries, deacons and deaconesses continued such ministries with town councils taking on some responsibilities for social welfare, such as orphanages and widows lodgings.

The 18th century Methodist revival in Britain awakened a national social conscience and produced numerous new initiatives in response to the social challenges of the Industrial Revolution. Following his successful fight to outlaw the slave trade (1807) after his conversion to Christianity, William Wilberforce co-founded the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the SPCA (1824).

Over the following century, many compelled by their Christian faith established voluntary movements towards the common good, including Henri Dunant (The Red Cross, 1863), George Williams (YMCA, 1844), Florence Nightingale (nursing), Elizabeth Fry (prison reform) and William and Catherine Booth (Salvation Army, 1865). Save the Children Fund (SCF, 1919) was founded by schoolteacher Eglantyne Jebb, appalled by the Allied treatment of children in the defeated nations of WWI, in her own words, after ‘there came to me the face of Christ’.

War devastation and dislocation catalysed the birth of numerous new agencies during and following the Second World War, including Catholic Relief Services (1943), Christian Aid (1945) and World Vision (1950). In 1947, two Quaker organisations were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for humanitarian service and dedication to peace and non-violence.

After WWII, Article 71 of the United Nations Charter (1945) made space for a new entity, the ‘non-governmental organisation’, with which its various agencies like UNESCO and WHO would have consultative relationships. A number of existing movements and organisations, some lay religious orders and Protestant mission movements, were ‘reincarnated’ as NGOs in order to enter into a formal relationship with the UN to serve a public mission.

However, only with the end of the Cold War and the collapse of communism was the climate favourable for NGO’s to multiply globally. In Soviet lands, where atheistic state-control was total, NGOs were illegal. The concepts of volunteer and voluntary organisation simply did not exist in the Soviet mind. Within a decade of the end of the Soviet Union, at least new 65,000 NGOs had been registered in Russia.

Historically, organisations and movements existing to promote some public good have been responses to the Golden Rule to ‘Love your neighbour’. Today more than two-thirds of all religious non-governmental organisations operate from biblical premises. Although Moslems outnumber Jews a hundred to one worldwide, Jewish agencies are roughly equal in number to Moslem agencies.

Faiths emphasising charity, personal responsibility and individual initiative are more likely to produce NGOs than those with fatalistic, other-worldly and inward-looking spiritualities. While various religions espouse the value of compassion, (the Koran repeatedly talks of ‘Allah the Compassionate’), historically those claiming inspiration from the Bible have a track record of translating words into action.

Till next week,