The sixth in a series of draft chapters for a popular-style illustrated coffee-table book about how the Bible has shaped so many facets of our western lives. The first chapter proposed that the Bible is the key for understanding Europe. The second, third, fourth and fifth chapters explored the Bible’s influence on western art and music, architecture and design, agriculture and gardening and business and economics respectively. Feedback is welcomed.

Europeans today may not quickly identify modern cities as places shaped by the Bible. Yet a closer look reveals the profound influence of the ancient Scriptures on the development of urban centres in Europe and beyond. To start with, the history of Jerusalem, where Christians believe Jesus was crucified and resurrected, has been shaped ever since by the claims of the three Abrahamic faiths–for better or for worse.

Rome, the capital of the greatest military and economic power the world had ever seen, succumbed to the Christian message of love, truth and justice in just three centuries. Ever since it has been the seat of one of the largest expressions of Christianity. Rome’s fall in 410 prompted Augustine of Hippo to write his hugely influential City of God, viewed as a cornerstone of Western thought, outlining human history as the tension between two cities: God’s and man’s.

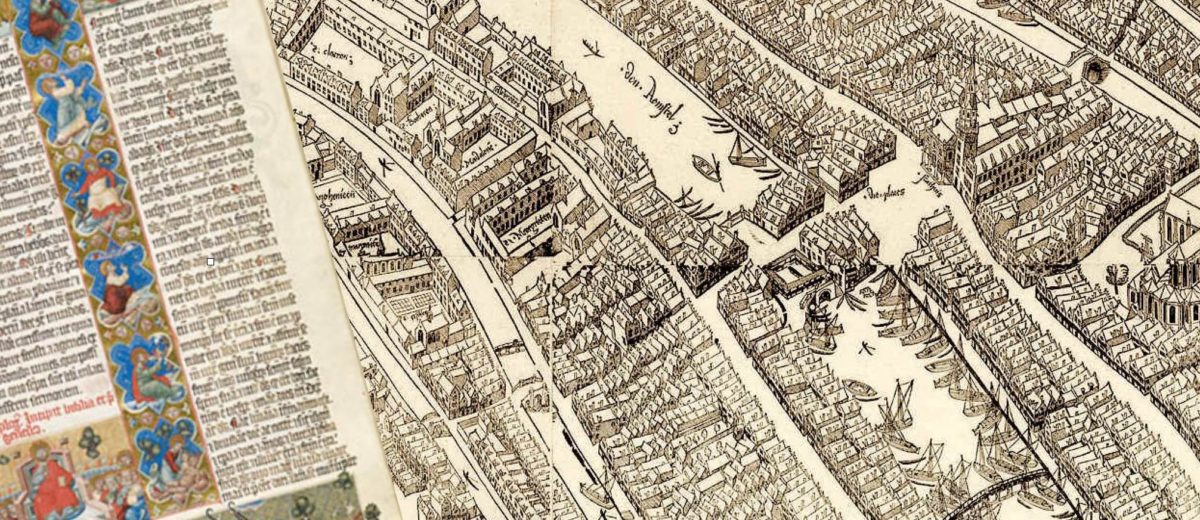

Monasteries–where the reading, reciting, singing and copying of the Bible were central–were often established on the sites of former Roman military garrisons, such as Paris, London, York, Utrecht, Cologne, Zurich and Regensburg. Other monasteries started in unsettled areas eventually grew into cities, as they attracted pilgrims, students, scholars, artisans, brewers, farmers and traders. St Gallen was settled by the Irish monk St Gall. Münster derives from the Latin: Monasterium. Munich’s name comes from the Old High German term Munichen, meaning ‘by the monks’.

Monasteries provided social services for the cities, offering care for the sick, homeless, poor, hungry and wayward. A map of any European pre-Reformation city will show a third or more of the urban area occupied by churches and monasteries. The Christian humanist scholar Erasmus asked, ‘what is a city if not one big monastery?’ For the monastery provided the model for a new form of society: the medieval city.

At the core of this model was the power to call community into being: the Biblical concept of agapè, selfless love. People were free to form public communities by making a vow–promissio–not based on family ties, or shared interests, but centred around an ‘ideal’. The city became a space for freemen and equals committed to mutual support, with a moral infrastructure built on the covenant and the personal vow, often renewed annually. Civil society presupposed self-restraint and promise-keeping.

Free trade guilds were covenantal communities regulating standards and conduct. The word ‘guild’ meant both payment or contribution, and sacrifice or worship, and reflected the guilds’ origins as being both secular and religious.

The Reformation brought the dissolution and secularisation of monastic properties, and thus a shift in social responsibilities towards the diocesan church and city elders. Later the Industrial Revolution greatly aggravated social needs in the increasingly-overcrowded cities. Institutions and movements incarnating an awakened Christian conscience led out with innovative responses; e.g. the Methodists and the Salvation Army in Britain, and deaconess movements in Lutheran and Reformed countries.

While William Blake contrasted the ‘dark satanic mills’ with visions of Jerusalem, others deliberately set out to build their own brick-and-mortar monuments to ‘progress’ in human wisdom, without recourse to the God of agapè. For many, Christianity’s faults–religious wars and unholy alliances with power–discredited its ability to inspire adequate civil social ideals. Yet the ongoing quest for alternative visions sustaining equality, freedom and brotherhood in cities and society at large remained elusive.

A century ago, the emerging Christian Democratic and Social Democratic movements both originally drew from the Biblical concepts of humanity as relational beings created in God’s image–homo socialis rather than homo consumus–to seek answers to the so-called ‘social question’.

Today the questions have broadened and deepened to embrace issues of unity with diversity concerning ethnicity, religion, gender, justice, environment and security. As in the past, the Bible remains an inspiration for exploring new social ideals for our cities and communities.

Till next week,