While millions this week will be celebrating Halloween globally, millions of Protestant believers around the world will also be celebrating the start of the Reformation exactly 500 years ago tomorrow. Is that just coincidence?

Actually, no. The city parades and festivals of the dead being enacted out on the world stage this week are related to what led to vigorous protests in 1517 from a stout Augustinian monk named Martin Luther.

For Halloween or Hallowe’en (meaning ‘hallowed’ or ‘holy’ evening) was the start of the three-day season in the Catholic liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead. That is, the saints (or hallows), the martyrs and all the faithful departed. Although the word Halloween was first used only around 1745, some traditions date from the ancient pagan Celtic harvest festival of Samhain, which the Church tried to christianise in the first millennium.

Samhain signalled the beginning of the ‘darker half’ of the year. During this liminal (transitional) time, the boundary between this world and the otherworld thinned. In this twilight zone, spirits and fairies were particularly active.

Catholic teaching on purgatory held that the souls of the dead maintained an in-between state for some time. Many believed those souls wandered the earth until All Saints’ Day. The eve before–Halloween–provided one last chance for the dead to avenge themselves on their enemies before moving to the next world. Hence the use of masks and costumes to trick such avenging souls.

Halloween celebrations were kept alive particularly in the Celtic regions of Britain, which included Ireland and Scotland. With waves of migration from those countries to North America in the 19th century, Halloween took root across the Atlantic.

Incensed

Back in 1517, Luther was not only theology professor at Wittenberg University but also the priest at the main city church. When his parishioners stopped coming for confession, he discovered they were going to surrounding towns to buy indulgences. Luther was incensed by this replacement of confession by offering salvation through indulgences.

For nearly a decade, parishioners had been told they could release the souls of loved ones from purgatory simply by buying an official-looking piece of paper. He realised his parishioners were being targeted by a fund-raising campaign for building St Peters in Rome, the so-called Peter’s Indulgence. So he began to preach against the practice. True repentance and penitence could not be replaced by the mere purchase of an indulgence, he taught.

On All Saints Eve, October 31, the peak of the season for indulgence purveyors to play on people’s fears about the souls of dead relatives, Luther was goaded into writing a letter to his church superiors, hoping to get rid of this abuse. In this letter he included his now famous 95 Theses which he hoped would provoke a discussion on the topic.

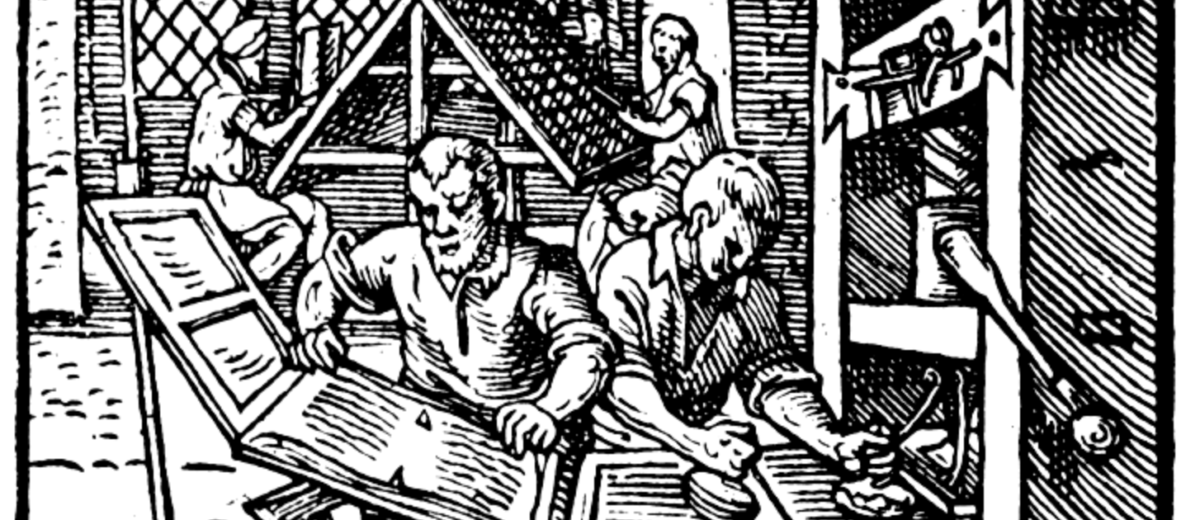

Luther sent the letter off to a few bishops and also to some friends. Some of the friends quickly started spreading the 95 Theses through the newly-invented printing press – in Leipzig, Nuremberg and Basel. A long fuse had been lit which would soon erupt into what we now call the Reformation.

No doubt the dramatic story of Luther nailing up his theses on the Wittenberg door will be retold endlessly this week. Yet today few scholars believe it to be true. Luther himself never wrote about it. Only after his death did the story begin to circulate. Most agree Luther was genuinely motivated by a desire to clear up these misunderstandings and not to provoke his superiors… at least at this stage of his career.

Rethink

In those regions which embraced the Reformation, Halloween came to be seen as incompatible with Biblical teaching. Purgatory became viewed with great suspicion of being a ‘popish notion’ contradictory to the core reformational teaching of salvation by grace and faith alone. The idea of restless souls of the departed dead from whom one needed protection by masks and costumes was now seen as unbiblical.

The Reformation that Luther and his fellow reformers found themselves leading would fundamentally redefine the place of humans in the world and the human relation to God. Rejecting intermediary institutions, particularly the papacy and the church as arbiter of salvation and grace, it brought about a total rethink about the individual’s place in the cosmos.

This would mean on the one hand the recovery of a biblical worldview, a reformed church and a renewed understanding of Christ as cosmic lord.

Ironically on the other hand, Luther’s initiative on October 31 is seen by many today as itself opening an new underworld of spirits of desacralisation, enlightenment and secularisation giving us our modern world with no place for the transcendent.

Doubly ironically, it is this secular world that delights once more to escape from reason into the fantasies of Halloween.

Till next week,