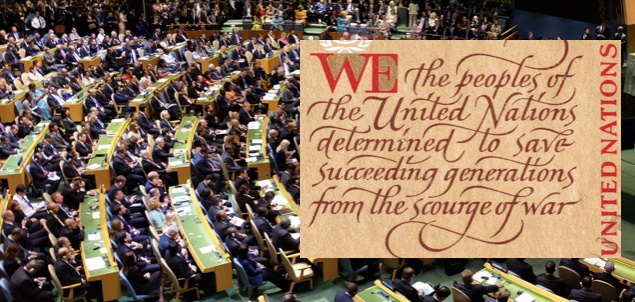

Eighty years ago, in 1945, the delegates who gathered in San Francisco to sign the Charter of the United Nations shared an understanding that peace rests on justice, human dignity, and shared responsibility.

Out of the devastation of the Second World War had come a yearning for moral renewal and a framework for peace. The United Nations was conceived within a moral atmosphere deeply permeated by Christian thought. Yet the vital role that Christians played in this vision is largely forgotten.

Signed and approved in June 1945, the charter came into effect on October 24 (i.e. 80 years ago yesterday), now recognised as United Nations Day. As an international treaty, it is legally binding on all member states and codifies major tenets of international relations, including the sovereign equality of states, the prohibition of the use of force, and the promotion of human rights.

Christian influence

The very notion that every person possesses ‘inherent dignity and equal and inalienable rights’ arises from the biblical conviction that all human beings are created in the image of God. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) of 1948 — a document whose drafting bore unmistakable Christian influence – provided the moral backbone of the post-war order.

Prominent Christians shaped that moral foundation. The American Presbyterian John Foster Dulles, later US Secretary of State, served as a key legal advisor at the San Francisco Conference. A lifelong active churchman, Dulles saw in the UN a means to channel moral law into international politics. President Roosevelt’s widow Eleanor chaired the UDHR drafting committee and spoke often of the Declaration as an effort to make concrete the ethical teachings of the Sermon on the Mount in political life.

Charles Malik, the Lebanese philosopher, theologian, and diplomat, was a Greek Orthodox scholar steeped in both philosophy and faith. He wrote the crucial Article 18 of the Declaration on religious freedom and the freedom of conscience. Providing the intellectual and moral clarity that helped bridge Western and Eastern traditions, Malik argued that “If man is not created in the image of God,” he said, “then the Declaration is meaningless.”

Alongside them, Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain proposed that people of diverse beliefs could agree on basic human rights even if they differed on metaphysical justifications—what he called ‘practical agreement on common principles’. The result was a document that, while secular in tone, was deeply indebted to Christian moral reasoning.

Christian Engagement

From the outset, Christian organisations recognised the UN as a moral as well as political arena. The World Council of Churches (WCC), formed in Amsterdam in 1948, saw in the UN a partner for peace, human rights, and development. Later, Christian agencies such as Caritas Internationalis, World Vision and Tearfund gained consultative status with the UN’s Economic and Social Council, working side by side with UN agencies to address poverty, displacement, and disaster relief.

The Holy See, granted Permanent Observer Status in 1964, has used its diplomatic presence to advocate for peace, disarmament, and human dignity. Successive popes—from Paul VI to Francis—have spoken at the UN, calling it a ‘moral centre’ for humanity.

Many Christians have viewed the UN as an expression of ‘common grace’—an imperfect yet necessary structure through which God restrains evil and promotes justice in a fallen world, while not mistaking it for the Kingdom of God. Others have seen in it a forum for prophetic witness, a place to speak truth to power and to advocate for the poor and the persecuted.

Yet Christian engagement has never been uncritical. Evangelical and conservative Christians have often accused the UN of promoting secular humanism and moral relativism, particularly around sexuality, reproductive rights and family life. Some apocalyptic interpretations have gone further, portraying the UN as a prelude to a ‘one-world government’ in prophetic end-times schemes.

Often Christians have lamented the UN’s failures—its paralysis during genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia, its limited action in Syria and Gaza, and the persistent inequality built into the Security Council’s veto system. For them, the UN’s sin is not overreach but timidity—a reluctance to act justly when great powers obstruct moral action.

Today’s Challenges

The moral vision that inspired the UN’s founders remains urgently relevant today. The morality of the post-war order is being brazenly challenged by leaders of both Russia and America. As Ukraine faces reconstruction after devastation, the challenge again is to rebuild not only cities and economies, but the moral foundations of a just peace. Imagine the difference if the moral swamp of post-communist Russia had been drained in the 1990s! There would be no war waging right now in Ukraine.

Reconstruction is not merely technical or financial, but spiritual and ethical. Today’s task in Ukraine is to rebuild on the same moral foundations the founders of the UN identified eight decades ago. Human dignity, grounded in the image of God, remains the only secure foundation for the rebuilding of nations.

Till next week,