The chaos of the Dutch railways caused by the snowstorm last Friday delayed the new professor’s arrival at his own inauguration – just as well for my wife and me caught up in the same confusion of delays and detours on our way to the Free University in Amsterdam.

Garbed in cap and gown, Professor Dr Govert Buijs belatedly took the platform in the university auditorium to present his oratio marking his official appointment to the newly-established Abraham Kuyper chair of political philosophy. His topic, he announced, was ‘Public love: ‘agapè’ as source for social renewal in times of crisis’.

Govert has supported us in the establishment of the Schuman Centre. Three years ago he addressed a small group of practioners and academics gathered to advise us on the centre, and spoke then on this same topic. Now, as professor, he presented a scholastic version of this talk.

Govert’s claim was that the concept of charitas or agapè, normally translated ‘love’, had played a central, formative role in Western culture, not only in the private sphere, but equally in the public domain. Love, he argued, had been a source of inspiration and a theme shaping our culture, especially at critical phases of development.

Implicitly or explicitly, our expect-ations of today’s social institutes were rooted in the concept of agapè, even when the dynamics of these institutions contradicted this value.

Strong sources

Quoting a Dutch columnist, Govert asked, ‘Do we really have to love one other to live together as citizens?’ His response was to ask if we really could live in community without a form of public love, at least in a society as ours that claimed to hold high standards. In the words of Charles Taylor, high standards need strong sources.

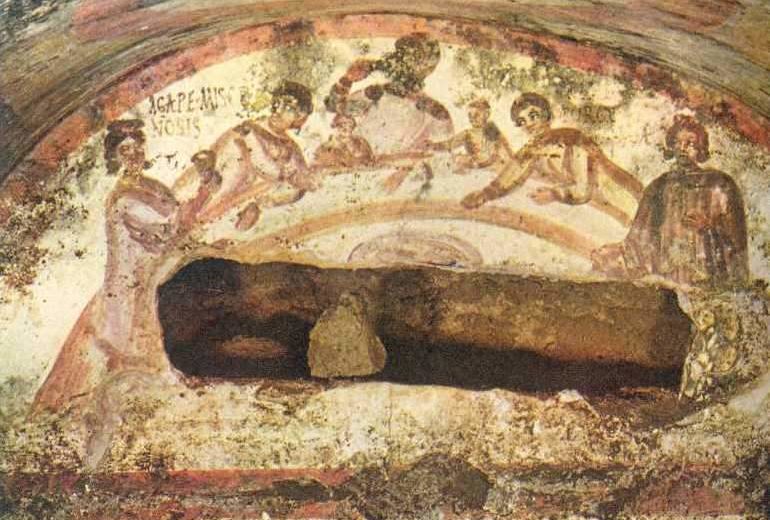

The word agapè had been created by the translators of the Septuagint when they could find no equivalent Greek word for a Hebrew concept that had been rooted in story, the story of God’s covenantal faithfulness, of consistently choosing the best for the other.

In the New Testament this concept was expressed in the frequent use of the phrase ‘one another’. This agapè was concrete, for individuals, for all, a free-choice commitment, egalitarian rather than hierarchical, transformational, hopeful and contagious. This word became the central concept of the New Testament, which stated even that ‘God is agapè’.

And this agapé had been fleshed out in Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. God had made a concrete choice for people, had embraced suffering, had opened a new future for humankind and had set individuals back on their feet.

Echoes of this love were found in many cultures, clarified Buijs, but was fundamental to the Christian tradition.

So, what did this have to do with the ‘real’, hard, competitive world shaped by Machiavelli or Hobbes? Or by Nietzsche, who mistrusted agapè in a world driven by self-love? Didn’t Adam Smith usher in today’s global capitalism by appealing to the self-interest of the ‘butcher, the brewer and the baker’?

Buijs urged his audience to read the context of Smith’s statement more closely to discover a Calvinistic concern for ‘universal benevolence’, and an exhortation to serve the other’s self-interest, in what he called Smith’s ‘work of mercy’.

Agapé revolution

Appealing to a seven-panel artwork, The seven works of mercy, painted by his namesake Cornelis Buys in 1504, the new professor reminded his listeners of the central role that mercy/charity/love/agapè hadplayed in the public domain in past times. In over an hour, far more space than we have here, he argued that an agapè-revolution had birthed, shaped and influenced all sorts of institutions at the heart of Western society.

These included the concepts of voluntary association, the social midfield or civil society, which monastic communities–themselves covenant-based, agapè-communities–pioneered as shelters for the sick, naked, hungry, thirsty, homeless and strangers. Such models grew into the city-states of northern Italy and Northwest Europe, spaces of freedom, equality and dignity, which had later prompted Erasmus to observe: What is a city but a big monastery?

A fresco in Siena’s city hall, explained Buijs, portrayed how faith, hope, love and justice were essential virtues for peaceful community life. Perhaps Europe’s current crises could awaken us to a new agapè-revolution.

Till next week,