The slogan ‘Never again’ evolved after World War Two rooted in the vow to prevent the recurrence of the Holocaust’s horrors.

It has been broadened over time into a universal commitment against racism, discrimination, and violence, while also serving as a call for action in various human rights movements.

But with the rise of populist nationalism, strongman politics and the abandonment of international law and order, as well as the passing of the generation with living memories of that war, ‘Never again’ risks being hollowed out on our watch.

Let’s revisit how the slogan emerged.

Three Jewish voices in particular helped develop the moral grammar articulated in the phrase:

- Forgetting, said Elie Wiesel, is how evil gets a second life.

- Auschwitz, warned Primo Levi, was not an aberration but a human possibility: “It happened, therefore it can happen again.”

- Evil, diagnosed Hannah Arendt, was something chillingly ordinary — ‘banal’, bureaucratic, legal, respectable. That meant never again to indifference, not merely never again to camps. The greatest crimes of the twentieth century were not committed by monsters, argued Arendt, but by ordinary people who obeyed, complied, and looked away.

“Never again” was thus never only about the past; it was a warning about human nature. Moral horror alone was not enough. It had to be institutionalised.

- Polish Jew Raphael Lemkin invented the word ‘genocide’ in 1944 after losing 49 members of his family, because existing law could not name the crime.

- Hersch Lauterpacht, a Polish Jew born near Lemberg (now Lviv), developed the idea of ‘crimes against humanity’, shifting protection from states to persons.

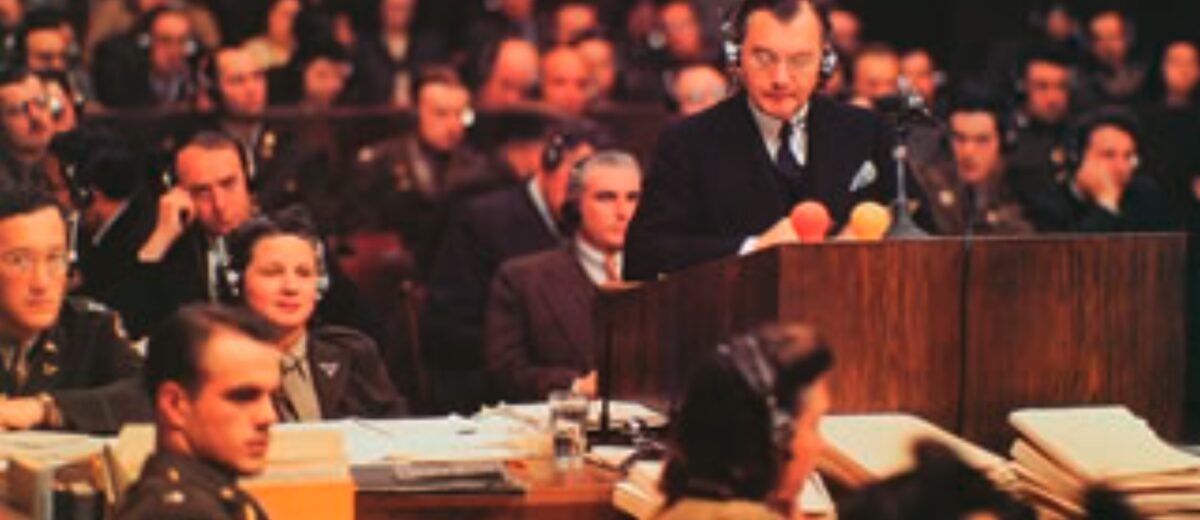

- Justice Robert Jackson was the driving force behind the creation and strategy of the Nuremberg Trials (at the podium in photo above), insisting on a process of justice over bullets-in-the-head favoured by the US military. ‘Just following orders’ was not a defence, the Trials established.

Law could restrain power when morality failed, these men believed. Their work led to the Genocide Convention (1948) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).

Often overlooked, yet crucial, were Christian voices of repentance and responsibility.

- Karl Barth insisted that the Church could not hide behind neutrality. Silence, he argued, was itself a political act of complicity.

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer (executed in 1945) became a posthumous witness that discipleship may require resistance, even at great cost.

- The churches, too, were forced into painful self-examination. German Protestants confessed their collective moral failure in The Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt (1945). Faith without courage became complicit. Christian faith which refuses responsibility for the world ceases to be faithful. Neutrality, Bonhoeffer insisted, is not innocence when injustice reigns.

The architects of a new Europe launched the European project not as an economic dream but a peace discipline. ‘Never again war between us’ became the political translation. Shared sovereignty and mutual accountability, binding former enemies into mutual dependence, beginning with the coal and steel industries, aimed to make war between partners materially impossible. Robert Schuman, Konrad Adenauer, Alcide De Gasperi—all shaped by dictatorship, prison, or exile—believed reconciliation had to be structured, not sentimental. It was a moral project and Schuman insisted it needed a soul.

Empty slogan?

But memory, passed on to generations not sharing the living experience, risks becoming harmless. Our memories need jogging afresh as to why ‘Never again’ emerged in the first place.

For Europe’s founding promise is being tested. Europe was built on the assumption that law matters, that borders cannot be changed by force, that memory should shape policy. If Europe cannot defend those principles when they are costly, then Never again becomes an empty slogan—not a foundation.

We have been watching the return of the warning signs – from both sides of the Atlantic: dehumanising language (‘parasites’, ‘vermin’, ‘traitors’), legalised exclusion of minorities, weaponised nostalgia (‘make our nation great again’), normalised lying and contempt for truth, and neutrality framed as wisdom. These are not new patterns. We recognise them from the 1930s.

As we approach the fourth anniversary of Putin’s bloody and ill-fated invasion of his southern neighbour, Ukraine forces a brutal question: What does ‘Never again’ mean when genocide-like practices are documented in real time—and still debated as ‘complex’?

Ukraine brings this crisis into sharp focus. Mass deportations of children, erased identity, deliberate targeting of civilians, cultural annihilation, the denial of national existence, the language of ‘re-education’ and ‘historical correction’—these are not anomalies of war but echoes of Europe’s darkest chapters. These are the very crimes postwar law was designed to prevent.

‘Never again’ does not promise that evil will not return. It promises that when it does, it will be named, resisted, and constrained. It demands memory that disturbs, not memory that consoles. It asks whether Europe still believes what it once declared: that human dignity is non-negotiable, and that silence in the face of atrocity is complicity.

Till next week,