The macabre spectre of death confronted us this week on various fronts. A tragic road accident in Tanzania, caused when a truck’s brakes failed, killed a dozen international YWAM leaders returning from a field study trip near Arusha.

The victims were key leaders of YWAM across Africa and beyond. The worst tragedy in the mission’s 64-year history is engaging a number of our close colleagues in demanding counselling of emotional pain of loss and shock as well as multiple associated logistical tasks. Eventually the age-old question of theodicy will cry out for answers: if God is good, loving, all-knowing and all-powerful, why does he allow bad things to happen?

Many who want to reject God have quoted the Roman poet Lucretius: “Had God designed the world, it would not be / A world so frail and faulty as we see.” Yet why do we intuitively know that such tragedies mean something has ‘gone wrong’?

Other worldviews like atheism, Hinduism and Buddhism cannot really define ‘evil’, ‘bad’ or ‘wrong’. Atheism says that pain is just part of the way things are. Life is just the survival of the fittest. Pantheism holds thet all distinctions are illusions, ‘Maya’ – that there is no distinction between good and evil.

Should we simply accept that we live in a world of pain? or that pain is an illusion? Or does our intuitive sense that pain, evil and tragedy were not part of the original design tell us that this is a good world gone wrong?

C.S. Lewis wrestled with these questions, firstly as an atheist on his journey towards faith. Yet if evil was real, he reasoned, then there must be an absolute standard by which it was known to be evil – and an absolute good by which evil could be distinguished from good. Much later, as a believer, he still wrestled with the problem of pain after his wife Joy died. That led him to write the book, The problem of pain. Our outrage at death as something that ought not to be is a clue that this is a good world gone wrong.

Good reason

The Christian philosopher Alvin Plantinga argues that the existence of evil is not a necessary contradiction to theism. The all-powerful, all-good God who created the universe has permitted evil, he argues, and has a good reason for doing so. What that good reason is, is not necessarily immediately – and may never be – apparent to us mere mortals.

The death of Russian opposition leader, Alexei Navalny, in a remote Arctic penal colony outraged much of the world this past week. His crime was to stand up for truth, opposing the gangsters in power. What the long-term consequences of his murder by poisoning (as is widely suspected) is not immediately apparent. Yet as I write these words, his funeral is being followed globally. In Moscow crowds outnumbering the police chant ‘Putin murderer’ and ‘Stop the war’. His ‘last word’ is being reported in newspapers and websites around the world–including his testimony of having become a believer.

“Now I am a believer, and this helps me a lot in my work, because everything becomes much, much simpler,” Navalny told the judge in his last appearance in court. “There is a book in which it is more or less clearly written what needs to be done in each situation. It’s not always easy, of course, to follow this book, but in general I try. And so, certainly not enjoying the place where I am, nevertheless, I have no regrets about what having returned (to Russia), about what I am doing. On the contrary, I feel such satisfaction. Because… I didn’t betray the commandment: ‘blessed are the thirsty and hungry for righteousness for they shall be filled’”

Bearing fruit

What God’s ‘good reason’ for allowing Navalny’s death, we cannot presume to know fully. His plea to his countrymen not to live the lie and not to be afraid may prove to be a significant blow to the structure of the current corrupt regime.

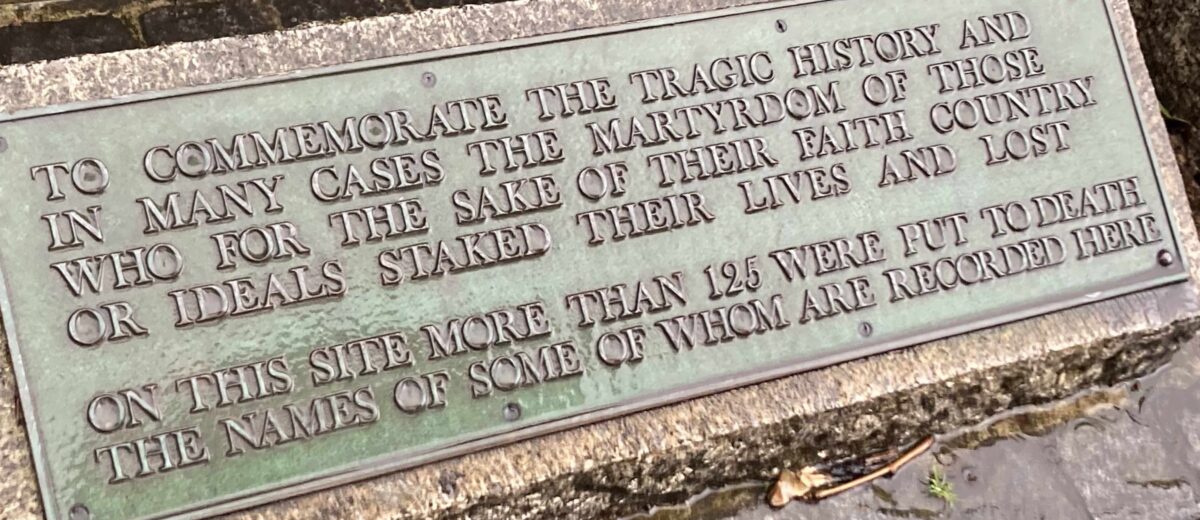

This week, on a three-day Heritage Tour in England with a small group of fellow pilgrims, I stood outside the Tower of London where gallows once stood. We reflected on the violent deaths of who those fell foul of Henry VIII and his successors (see photo). What were God’s ‘good reasons’ for allowing the unjust deaths of those martyred during the Reformation?

Jesus talked of seeds falling into the ground and dying before bearing fruit. In God’s purposes, death is not the final word. Responding to the shock of the tragedy in Arusha and the outrage of Navalny’s death, we must choose to trust that God has a ‘good reason’. Corrie ten Boom, well acquainted with grief and death, often recited this anonymous poem when speaking about her wartime experiences:

My life is but a weaving between my Lord and me. / I cannot choose the colors, He worketh steadily. / Oft times he weaveth sorrow, and I in foolish pride, / Forget He sees the upper, and I the underside./ Not till the looms are silent and the shuttles cease to fly, / Will God unroll the canvas and explain the reason why /The dark threads are as needful in the Weaver’s skillful hand / As the threads of gold and silver in the pattern He has planned.

Till next week,