The fourteenth in a series of draft chapters for a popular-style illustrated coffee-table book about how the Bible has shaped so many facets of our western lives. Feedback is welcomed

For many, the principle of the separation of church and state suggests that religion has no role in modern politics. Democracy, we are told, comes to us from the Greeks; so who needs religion when it comes to politics?

Political ideologies however are by nature religious. They express beliefs about the nature of reality, humanity and society. They are based on ideas of authority and power. An ideology reflects faith in a solution for a better world, whether it be conservatism, socialism, communism, liberalism, fascism or nationalism.

Which faith perspectives have primarily shaped western politics? The word ‘democracy’ has Greek roots, but can we really trace a direct line from Athens to Brussels, or to London, Paris or Washington?

For better or for worse, the Bible has been by far the greatest influence on political and governmental thinking in Europe since the late Roman empire right up until modern times. From Constantine to Henry VIII and beyond, the Bible was the source of authority by which governmental forms were legitimised; whether tyrannical and authoritarian, or democratic and egalitarian.

From the emergence of Christendom, the relationship between throne and altar, emperor and pope, king and cardinal, was marked by tension and competition. Neither side enjoyed complete monopoly. What role did religious authority play in legitimising the throne? The Bible depicted Old Testament kings being anointed with divine authority and sanction: Samuel with David, and Zadok with Solomon. (Handel’s anthem Zadok the Priest has been used in every British coronation since George II in 1727).

The New Testament also seemed to side with the reigning powers. Paul instructed the Romans in chapter 13: For there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God. Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God: and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation.

And yet, from the early middle ages onwards, the last word on the legitimacy of the ruler usually lay with the spiritual leader. Boniface told the king of Mercia that ‘it was not your own merit but the abundant goodness of God that appointed you king and ruler over many’. Kings and rulers had responsibilities before God. They had to rule justly, protect their people, value life, protect the weak and champion the church.

Over time, this led to the conclusion that ‘no man can make himself king, but the people have the choice to choose a king whom they please’, as was preached already late in the first millennium. The Bible thus offered both legitimacy and limitations to the throne in what was still a feudal society with a ‘God-ordained’ social order from king to peasant.

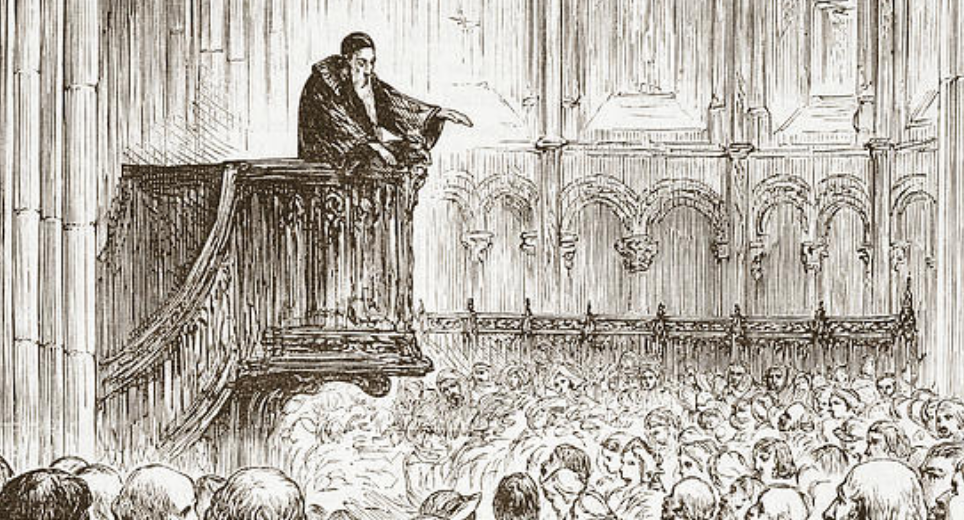

As the Reformation erupted across Europe in the 16th century, Bible translations in the languages of the European peoples became subversive instruments – just as conservative church leaders had feared. Bible translators like Erasmus, Luther and Tyndale wanted to make God’s Word available to ‘the ploughboy and the prostitute’ on the one hand, yet on the other still preached obedience to the reigning authorities. But they and their fellow Bible translators and reformers had unleashed the forces of spiritual democracy. The Bible was for all, and that had profound democratic implications.

In Geneva, John Calvin further developed Reformational thinking with revolutionary consequences. Trotsky, Lenin’s co-revolutionary, viewed Calvin as one of the two most revolutionary figures in western history, along with Marx. Calvin taught on the dangers of monarchy (I Samuel 8), the need for limited government, and that royal authority was contingent on meeting the conditions of God’s covenant. The Mosaic model of elders elected by the people (Exodus 18) inspired both a church government of elected elders and a civil government of elected representatives. Calvin introduced separation of powers into local government, predating Montesquieu’s doctrine by two centuries. Even the best leaders needed accountability and mutual correction, he taught.

Bible-inspired ideas spread from Geneva to the Dutch provinces, supporting rebellion against the Spanish and the formation of the Dutch Republic; to Scotland where John Knox led the Presbyterian Reformation; to England where parliamentary government emerged; and to the American colonies which cast off a ‘tyrannical monarchy’ to set up a democratic republic built on the Christian religion, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed the following century.

Arguments that democratic freedoms first required emancipation from Christianity are countered by recent research demonstrating the pervasive influence of protestant missions on the growth of stable democracy globally: through the spread of religious liberty, mass education, mass printing, newspapers, voluntary organizations and colonial reforms. (see The Missionary Roots of Liberal Democracy, Robert Woodberry).

The Bible also directly inspired Europe’s fresh post-war start through forgiveness and reconciliation. For the European project was conceived by men like Schuman and Adenauer as embodying the teachings of Jesus to love God, neighbour and enemy.

Till next week,