Advent was never part of the unadorned worship of my evangelical Baptist upbringing which eschewed religious ritual and liturgy.

Yet it has been an essential season in the calendar of much of the Church, enriching worship throughout the centuries.

Nobody quite knows how or when Advent became part of that calendar. While the dating of Easter and the death and resurrection of Jesus was always tied to the Passover, it took longer for his birth to be associated with the winter solstice, the shortest and darkest day of the year in the northern hemisphere.

Once December 25 was accepted for the liturgical celebration of Jesus’ birth, a period of preparation of heart and soul including prayer, worship and fasting – corresponding to Lent before Easter – was introduced by councils in Saragossa (Zaragoza) in today’s Spain and Tours in today’s France.

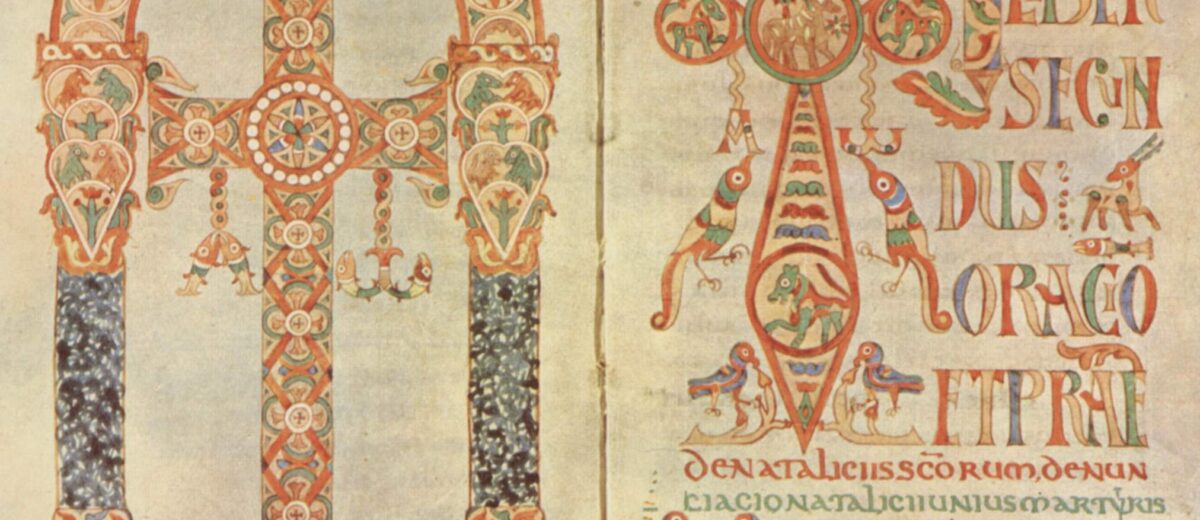

Readings for Advent are included in one of the oldest manuscripts of Christian liturgy, the beautifully illustrated Gelasian Sacramentary (see photo), which Boniface used on his mission to Europe in the mid-eighth century.

In many western traditions, Advent began the new liturgical year on the fourth Sunday before Christmas (always falling between 27 November and 3 December), ending on Christmas Eve on 24 December.

Double meaning

For much of its history, Advent carried a double meaning generally lost in today’s celebration focussed exclusively on the Incarnation. For the Latin word adventus was the translation of the Greek parousia, meaning ‘coming’, now usually associated with the Second Coming. Yet originally Advent focused on both the coming of Christ in human flesh as well as his Second Coming.

The first two weeks of Advent helped believers prepare their hearts for the Second Coming by confession of sins and prayer for the speedy return of the Lord. The last two weeks of Advent then reflected on the first parousia, when, as Athanasius put it, ‘God became man so that man might become god’.

(Lest that formulation of ‘theosis’ sounds a little too unorthodox, we could rephrase his words to: ‘the Son of God became the Son of Man so that the sons and daughters of men might become sons and daughters of God’).

This double meaning in Advent history sets the Christmas story in its larger cosmic context. The whole Old Testament pointed in hopeful expectation towards the hinge moment of the Incarnation. In turn, the Christmas narrative represented new hope for humanity: ‘Today in the town of David a Saviour has been born to you’ (Luke 2:11.) The First Coming itself pointed towards the climactic event of the Second Coming, the Final Judgement and the Restoration of all things and the ‘balancing of the books’ of history.

Third meaning?

Advent and Christmas are not mere occasions of nostalgia and warm fuzzy feelings. This is a season to reflect on our hope in Christ, in present and future dimensions.

Catholics and Lutherans saw a third meaning to Advent. In addition to the Incarnation in Bethlehem and the future Second Coming, they understood the Eucharist to be a perpetual sacramental coming of his Real Presence. They expected God the Son to show up in each Eucharist celebration.

Believers from other traditions can appropriate this third dimension of Advent by approaching prayer and worship with the expectation that Emmanuel – God with us – is indeed present, coming towards us to hear our prayers and bear our cares.

Mary’s song, The Magnificat (Luke 2:46-55), reveals the mother of Jesus as being pregnant with the hope of God’s continued action in human history, showing mercy, performing mighty deeds, scattering the proud, pulling down rulers from their thrones, lifting up the humble and sending the rich away empty and fulfilling his promises.

Advent this year comes as headlines continue to report violent atrocities in Ukraine and Russia, Israel and Gaza. We may be discouraged about the social, economic, environmental and political crises closing in seemingly on all fronts. Yet Advent urges us to realise God has acted in human history, dwelling among us in human form to bring us hope that he is the lord of history, lord of the cosmos, and will come again to balance the books.

A saying I recently came across, and at first thought to be rather trite, was: All will be okay in the end. If it’s not okay, it’s not yet the end.

This Advent, let us recover this double, or even triple, meaning of the season, by reflecting on the Christmas story as the promise of God’s continued action in our world; by realising that he has promised to draw near to us in the here and now as we draw near to him; and by yielding ourselves, as did Mary, to be his servant however he might want to use us.

And to accept that the disorder, injustice and inequality around us means that the end is not yet.

Till next week,