Imagine a world without love: where might is right, money trumps justice, indifference cancels out compassion, and cruelty offers entertainment; a world shaped by the realpolitik of Machiavelli or the nihilism of Nietzsche.

Some leading intellectuals fear we are headed towards such a world as the memory of Christian values fades. Public figures including Niall Ferguson, Roger Scruton, Douglas Murray, Jordan Peterson and Tom Holland – not practising Christians – have in recent years expressed their fears about the kind of society to which secularism is leading.

Historian Ferguson has come to see ‘that you can’t base a society on atheism… (which) particularly in its militant forms, is really a very dangerous metaphysical framework for a society’. The biggest disasters that we likely faced were actually related to totalitarianism, he has said, because that was the lesson of the 20th century. Pandemics killed a lot of people in the 2oth century, but totalitarianism killed more.’

Conservative philosopher and cultural Christian, Scruton, struggled personally to believe yet saw that Christianity was in many ways the soul of Western civilisation, and that the uniquely Christian concept of forgiveness was utterly indispensable to its survival.

Murray, a self-described ‘Christian atheist’, acknowledges the sanctity of human life to be a Judeo-Christian notion ‘which might very easily not survive [the disappearance of] Judeo-Christian civilisation’.

Holland, who told me in a Schuman Talk that he would like to be able to believe, came from his study of ancient civilisations to see that Christianity was a revolution so complete that even its critics must borrow precepts from Christianity to do so.

Mercy works

Dutch professor Govert Buijs, himself a believer, has been making the same point for well over a decade. The Christian concept of agapè love, he says, has played a central, formative role in Western culture, not only in the private sphere, but equally in the public domain. Love, he argues, has been a source of inspiration and social renewal as European civilisation developed. Implicitly or explicitly, our expectations of today’s social institutes were rooted in the concept of agapè, even when the dynamics of these institutions contradicted this value.

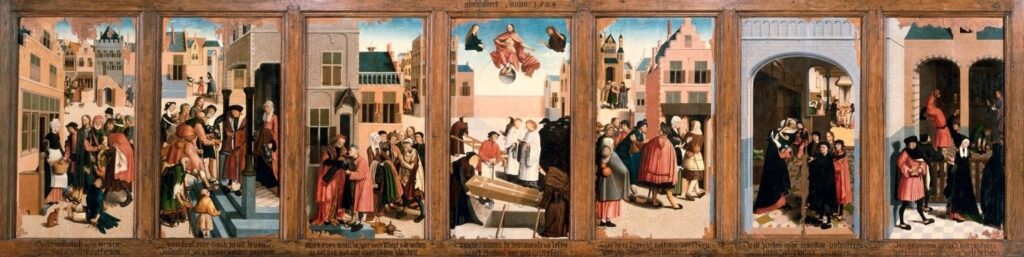

In this month’s Schuman Talk, he referred to a seven-panel artwork, The seven works of mercy, painted by his namesake Cornelis Buys in 1504, now hanging in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Set in the Dutch city of Alkmaar, these seven panels depict the works of mercy Jesus spoke of in Matthew 25: feeding the hungry, quenching the thirsty, clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless, caring for the sick, visiting prisoners – plus a seventh added later, burying the dead. A Jesus figure is present in each of the panels, (as circled above in the detail of the sixth panel: caring for the sick) reminding us of his words: ‘As you have done this to the least of these my brothers, you have done it to me’.

Govert explains that the word agapè had been created by the translators of the Septuagint when they could find no equivalent Greek word for a Hebrew concept that had been rooted in story, the story of God’s covenantal faithfulness, of consistently choosing the best for the other.

Agapè-revolution

In the New Testament this concept was expressed in the frequent use of the phrase ‘one another’. This word became the central concept of the New Testament, which stated even that ‘God is agapè’. And this agapé had been fleshed out in Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. God had made a concrete choice for people, had embraced suffering, had opened a new future for humankind and had set individuals back on their feet. Echoes of this love were found in many cultures, clarified Buijs, but was fundamental to the Christian tradition.

Govert challenges the dominant three-phase narrative of European history, which starts with the Golden classical age, followed by the Dark Ages of Christianity, ‘restored’ by the Renaissance and Enlightenment into the modern secular age.

These so-called ‘Dark Ages’ had seen the birth of an agapè-revolution, shaping and influencing all sorts of institutions at the heart of Western society. These included the concepts of voluntary association, the social midfield or civil society, which monastic communities–themselves covenant-based, agapè-communities–pioneered as shelters for the sick, naked, hungry, thirsty, homeless and strangers.

Such models grew into the city-states of northern Italy and Northwest Europe, spaces of freedom, equality and dignity, which had later prompted Erasmus to observe: What is a city but a big monastery? Covenant-based monasteries also inspired Europe’s universities, professional guilds, town cooperations, and contributed to the development of democracy and equality for women.

Govert suggests Europe’s current crises of economy, climate-change and pandemic could awaken us to embrace a new agapè-revolution, with an economics of cooperation instead of competition, and communities truly seeking the common good for all.

Till next week,