As democracy, freedom of speech, human dignity and rights come under increasing threat even in the heart of the western nations, we are being forced to realise we cannot take these elements of our western civilisation for granted anymore.

While essential for our lifestyles in free nations, none of these facets are self-evident or self-perpetuating. They have been bequeathed to us by those who often paid a heavy price.

The past two weeks have offered occasions for remembering how the past 75-year long phase of peace in most European nations began. On Europe Day, May 9, we recalled the Robert Schuman story in Warsaw at the State of Europe Forum. The following week in the European Parliament in Brussels, a gathering sponsored by Orthodox, Catholic, Ecumenical and Evangelical streams focused on the spiritual roots which inspired Schuman and his colleagues Adenauer and De Gasperi to ‘rebuild Europe on Christian foundations’.

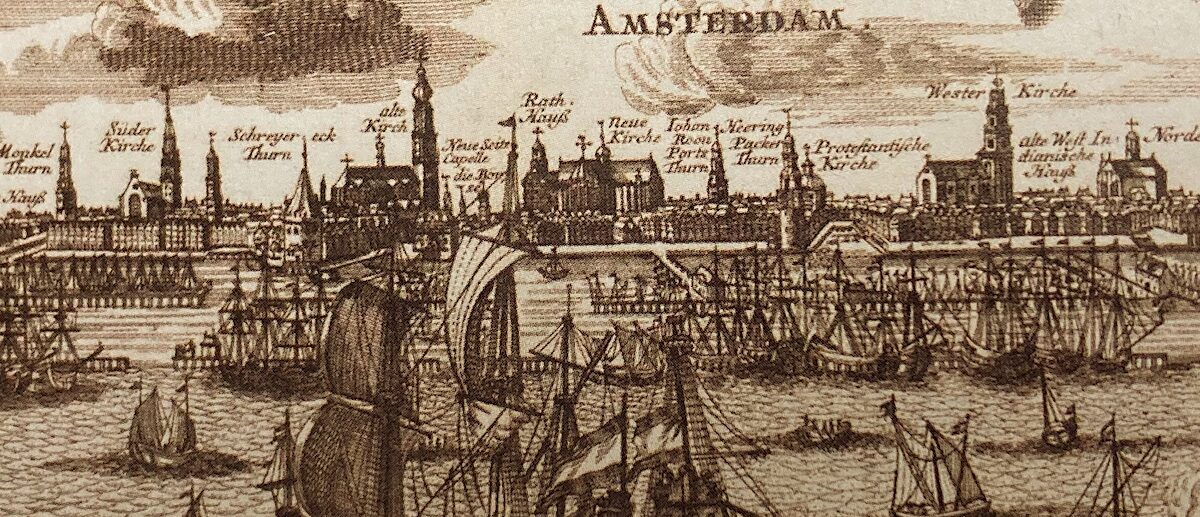

Back in Amsterdam this weekend, we resume the Geloof in Mokum series of events tracing the influence of faith on the development of the city over nine centuries. After exploring the influence of Catholicism from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, we are about to ponder the transforming impact of Reformational ideas on the city – and far beyond.

For Amsterdam became the world’s leading city for the century after these ideas took root – outperforming Rome, Antwerp, Paris and London. I like to describe the city as ‘the womb of the modern world’, as it gave birth to many facets of modernity. World cities including New York, St Petersburg and Cape Town were born out of Mokum, as the Yiddish-speaking Jews from Central and Eastern Europe called this city of refuge to which they flocked.

Amsterdam’s story is a microcosm of the European story, being fundamentally shaped by the story of the Bible – and then, paradoxically, by the rejection of that story. That latter development comes later in our Geloof in Mokum series.

Midwife

But for now we explore the midwife role of Reformational ideas in the birth of a modern world shaped by the values and concepts above often taken for granted. Tomorrow afternoon (Sunday) we gather in the Noorderkerk, one of Amsterdam’s first protestant churches, built in an octagonal shape to thrust the pulpit more into the centre of the congregation seated around the Word of God. Professor Mirjam van Veen of the Free University will describe why and how the sixteenth-century Amsterdammers embraced the Reformers’ teachings, rejected the hierarchical authority of the Roman Church and the Holy Roman Emperor, replacing it by the authority of the Bible.

Historians and philosophers recognise that the Reformation helped deliver key aspects of what we consider modern: individuality, critique of authority, literacy, pluralism, democracy and entrepreneurship. Most would also add that it was not the sole ‘midwife’. Modernity did not spring fully formed from the Reformation alone.

Yet the Reformation, particularly Martin Luther’s emphasis on sola scriptura (scripture alone) and sola fide (faith alone), encouraged individuals to interpret the Bible for themselves. This shift promoted the idea of personal responsibility and conscience, which became central to modern conceptions of the individual and human rights.

By questioning the authority of the Pope and the Catholic Church, reformers legitimised the critique of established power. John Calvin taught that Christians had a duty to oppose tyrants who transgressed God-given boundaries. This spirit of questioning extended beyond religion, fueling movements that challenged political and intellectual authorities including the Dutch rebellion against the Spanish, and later the American Revolution.

Tolerance

The Reformation greatly boosted literacy and the use of the printing press, as reading the Bible became a spiritual imperative. This helped spread ideas rapidly and empowered a more informed and critical public—an essential feature of modern democratic societies.

Although the Dutch Republic was officially Calvinist after the Reformation, it adopted a relatively tolerant stance toward other religious groups (like Jews, Lutherans, Remonstrants, Mennonites and Catholics). This tolerance attracted skilled refugees, Huguenots from France and Protestants from the Southern Netherlands (modern-day Belgium). These groups brought with them capital and commercial expertise, greatly enriching Amsterdam’s economy and cosmopolitan culture.

Amsterdam, with its Protestant tolerance became Europe’s most important printing hub in the 17th century. Exiles and intellectuals (like René Descartes and John Locke, who published in Amsterdam, the Pilgrim Fathers and Jan Amos Comenius) flocked to the city because of its freedom to print and disseminate new ideas—further boosting its international soft power.

Max Weber famously linked Protestantism (especially Calvinism) to the ‘spirit of capitalism’, arguing that Protestant ethics supported rational planning, frugality, and hard work—qualities associated with modern capitalist economies.

In these times of growing geopolitical tension, we do well to pause and reflect on how these freedoms and rights were won. And through negligence, ignorance and prejudice can be lost.

Till next week,