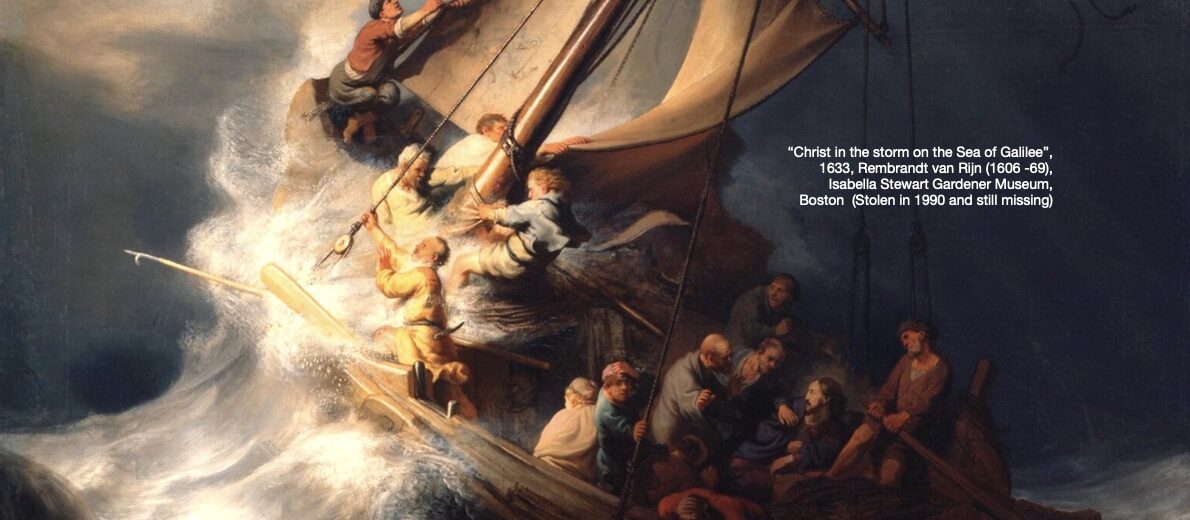

Rembrandt’s dramatic painting of Jesus and his disciples caught in a storm on the Sea of Galilee in a Dutch fishing boat contextualised the gospel story for his seventeenth-century viewers.

Still in his mid-twenties when he painted this, his only seascape, soon after moving to Amsterdam from Leiden, Rembrandt depicted fear and desperation in the faces of the disciples struggling to prevent their boat from smashing onto the rocks in the left of the picture. The artist’s contrast of light and darkness, his trademark chiaroscuro technique, heightens the sense of impending disaster with the waves and spray breaking over the sides of the vessel tossed by the fierce wind sweeping from left to right across the scene.

While Rembrandt has half the disciples wrestling in their own strength with sails, ropes and tiller, the others are clustered in the shadows, one even throwing up overboard. (See full painting here). Our eye is eventually drawn to the aft of the boat by the lines of harpoon and boom converging on the unperturbed, slightly haloed figure of Jesus. Two agitated disciples demand his attention. The blue figure clutching the rigging amidships looking straight at the viewer is the artist himself, pulling us into the picture as if to ask, what would you do in such a storm? Struggle desperately, throw up or turn to Jesus?

Those who know the story, as told by Matthew (8:23-27), Mark (4:35-41) and Luke (8:22-25), recognise the moment the terror-stricken disciples shake the sleeping Jesus awake, saying, “Master, Master, we’re going to drown!”

Jesus, the still point of the turbulent scenario, stands and rebukes the wind and waves. The storm subsides. Calmness prevails. Awe, wonder and holy fear grip the disciples.

“Who is this man?” they ask each other.

This story is part of the unfolding revelation to the disciples of the full identity of their Master, climaxing in the Resurrection and Ascension. ‘This man’ was none other than the Son of God, Lord of creation! That gradual unveiling would radicalise their lives, transform their worldviews and lead to martyrdom for all of the Eleven except John.

Storm clouds

How would we contextualise this story today?

Storm clouds are hemming us in on each side, it seems. Last week the UN secretary general warned that the era of global warming had now become the era of global boiling, after scientists confirmed July was the world’s hottest month on record. “Climate change is here. It is terrifying. And it is just the beginning,” he cautioned, aware that the floods, fires and violent weather will disrupt the lives of many millions.

The current blockbuster film ‘Oppenheimer’, coupled with Putin’s frequent threats to use nuclear weapons and the urgent warning from over 100 medical journals that the danger is ‘great and growing’, remind us that the threat of nuclear annihilation did not end with the ‘end’ of the Cold War.

My last weekly word explored the ‘strange new world’ we now live in where our primary identities are defined by our sexual preferences – how we think about our sexuality, not what our bodies tell us; a world in which ‘inclusion’ leads to exclusion; ‘freedom’ leads to intolerance; ‘diversity’ insists on conformity; the ‘abnormal’ has become normal. Can this lead to a flourishing future?

Serious threats to democracy and security come from within our national borders and beyond: foreign interference in elections; disinformation and fake news; physical and cyber threats to the democratic institutions; and foreign interference in public office, political parties and universities. This week Trump faced serious criminal charges for conspiracy to defraud the US, further polarising American politics. Unfortunately, what happens in the US has consequences for much of the rest of the world. As does Putin’s misjudged war in Ukraine – already raging for nearly a decade and showing no signs of just resolution.

Awe, wonder and holy fear

‘Our Changing Europe’ is the theme of this year’s Summer School for European Studies (Aug 21-24). You can still join us. Each day we will begin with reflections on artists’ portrayals of Jesus: Rembrandt van Rijn, Vincent van Gogh, Marc Chagall and the lesser-known American, Ed Knippers. How can we anchor our responses to the storms raging around us today on Jesus, ‘the still point of the turning world’, to use T.S.Eliot’s famous phrase?

Responding to our changing Europe requires for us a deeper revelation and understanding of Jesus Christ, not merely as ‘saviour of souls’, but as Lord of history, Lord of the cosmos, God Incarnate, the One through whom and for whom all things were made, and in whom all things hold together (Col. 1:16,17).

In the midst of our storms – whether global or local, universal or personal – we need to bring our anxieties to the One who rebuked the wind and the waves. “Who is this man?” we should constantly prod ourselves. And allow awe, wonder and holy fear to grip our hearts.

Till next week,