The seventeenth in a series of draft chapters for a popular-style illustrated coffee-table book about how the Bible has shaped so many facets of our western lives. Feedback is welcomed.

The Bible has been blamed for all sorts of violent atrocities including the Crusades, the Inquisition, religious wars, forced conversions and other forms of religious extremism.

And not without reason. Old Testament passages tell of wholesale massacres of men, women and children, and of David being praised for slaughtering ‘tens of thousands’ in comparison with King Saul’s mere ‘thousands’. These are difficult passages for 21st century minds to accept. Some even call for this ‘violent book’ to be banned, along with the Koran, used by Islamists to justify religious violence today.

However, for over two thousand years the Bible has inspired the search for peace among Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, western Protestant and pacifist streams, and their respective political expressions.

The church of the first three centuries was a persecuted minority practicing a ‘turn-the-other-cheek’ pacifism. Justin Martyr (c.100-c.165) wrote that ‘we who formerly killed one another not only refuse to make war on our enemies but…freely go to our deaths confessing Christ.’ Tertullian (c.160-c.220) taught against wearing any uniform which symbolised a sinful act.

After Emperor Constantine embraced Christianity in the fourth century, believers began sharing responsibilities for the temporal order. Two Latin bishops, Ambrose (c.339-397) and Augustine (354-430) developed a just war theory based on two presuppositions: one, peace was God’s intended order for humanity; two, fallen human nature required a legitimate authority to wield the sword to resist evil, uphold justice and defend the weak. Augustine put it this way: ‘it is iniquity on the part of the adversary that forces a just war upon the wise man.’

Athanasius and Basil, fathers of the Eastern Church in the fourth century, recommended that soldiers who killed enemy soldiers be pardoned; although, added Basil, communion may have to be withheld for three years ‘due to their uncleanness’.

Christian Romans now saw themselves as the New Chosen; the newly Christianised empire as the New Israel; Constantinople as the New Rome and the New Jerusalem. Their mandate was to defend themselves against pagans and infidels, and later Moslems and even Western Christians, as Israel had in the Old Testament under Moses, Joshua and David. ‘Self-defence’, ‘pursuit of peace’, ‘recovery of lost territory’ and ‘averting greater evils’ became accepted justifications for warfare.

Both Eastern and Western Christendom adopted practices ‘sanctifying’ military activities including military chaplains, pre-battle blessings, religious services on the battlefield, relics and other religious symbols accompanying troops in battle and special liturgies for the fallen as well as for victories – all practices still used widely today.

The Crusades, as argued by Pope Innocent IV, were against an ‘unjust occupation of lands unjustly expropriated and exploited by those who had no right to it’.

In the Middle Ages, the Peace of God (Pax Dei) movement emerged in Western Europe to protect church property, agricultural resources and unarmed clerics, followed by the Truce of God (Treuga Dei) movement to limit the days of the week and times of year when the nobility could engage in fighting. Large crowds witnessed vows being made to uphold the peace on threat of excommunication for violation. A ban on the use of certain weapons against fellow Christians was an early attempt at ‘arms control’.

The Reformation saw a continuation of the Catholic and Orthodox views of just war in the new territorial churches. Some mainstream Protestants viewed the duty of secular governments to include the protection of society from apostacy (as had Catholic and Orthodox authorities before them), by which the burning of heretics could be justified. As persecuted minorities, however, Anabaptists revived the pacifism of the early church.

Calvin raised the possibility of rebellion against tyranny, inspiring both John Knox (Scotland) and William of Orange (Holland) towards armed resistance. The Geneva Bible contained translations and commentaries supporting disobedience to wicked rulers. Calvinistic theology was deployed also during the English Civil War and the American Revolution to justify a ‘divine mandate to reform the political order’.

Scholars trained in the Calvinist (Hugo Grotius) and Lutheran (Samuel von Pufendorf) traditions laid foundations for modern international law and the later emergence of global institutions for the maintenance of peace, such as the United Nations.

Swiss evangelical, Henri Dunant, appalled by suffering he witnessed on the battlefield, initiated the 1864 Geneva Convention ‘for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field’. Today the Geneva Conventions define basic rights of wartime prisoners, establish protections for wounded and sick, and for the civilians in and around a war-zone.

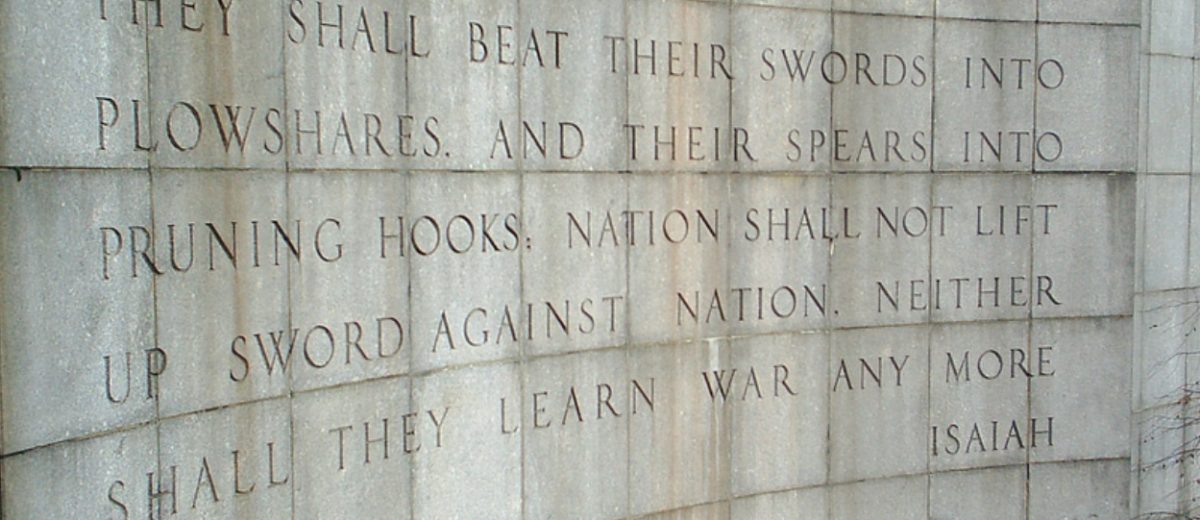

The words of the prophet Isaiah engraved on the United Nations Plaza in New York express the age-old dream of swords being beaten into ploughshares and witness to the incomparable contribution of the Bible towards world peace.

Till next week,