It was a busy European week.

On Monday, Theresa May refused to rule out a no-deal Brexit or to keep Britain in an EU customs union as she sought a way to take her nation out of the Union.

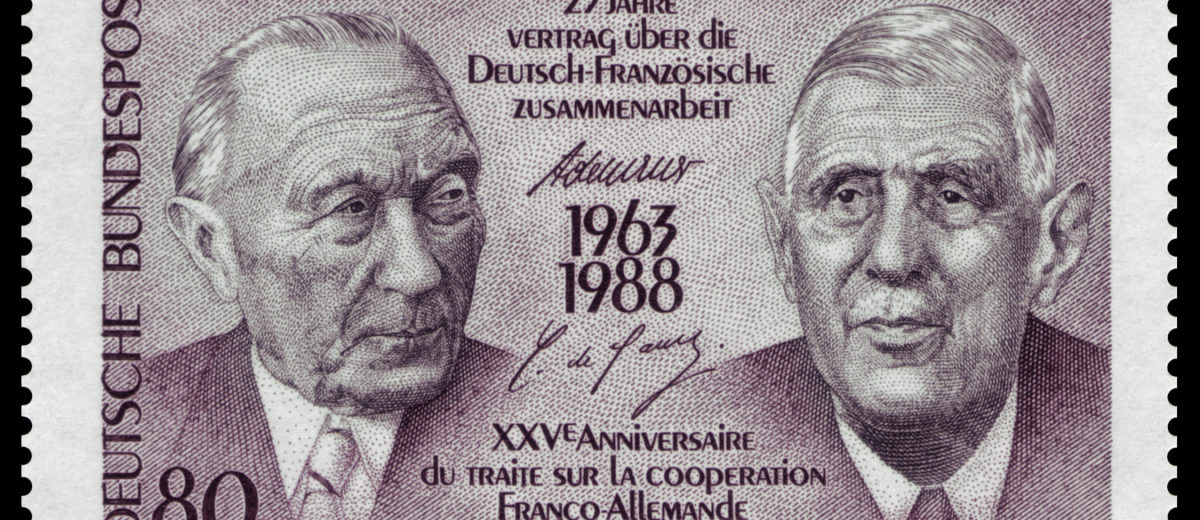

On Tuesday, Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron met in Aachen to sign a new treaty of German-French cooperation, exactly 56 years after their predecessors, Adenauer and De Gaulle, put their signatures to the first ever such treaty.

On Wednesday, I flew to Rzeszow in Poland to participate in the 12th Economic Europe-Ukraine Forum where, over Thursday and Friday, 600 politicians, academics economists, defence specialists, military and business leaders from Central and Eastern Europe dialogued about Ukraine’s place in the future Europe.

On Saturday, back in the Netherlands, I listened to two senior Dutch professors on European integration interact with ambassadors from Poland and Romania at a symposium on Europe’s place in the world today.

My notebook and my brain are full. But my conclusions from the week’s events are as follows: the European project is at heart about reconciliation, remains the only way for Europe to move forward, and, despite the alarm over Brexit, continues to offer hope for nations from the Balkans and the east lining up for membership.

That project did not begin in 1963, as readers of news reports this week about the Merkel-Macron meeting could have concluded. Hailed as an historic step of reconciliation between these two habitual enemies, the 1963 treaty was approached by the wily old French general in a very different spirit from the original reconciliation in 1950 between Chancellor Adenauer and Robert Schuman, the French Foreign Minister.

Humility

Schuman realised during the war that lasting peace could only come to Europe if there was true reconciliation between the two nations whose geography and history had destined them to a pivotal role in the well-being of Europe. Even while imprisoned by the Nazis, he had smuggled out a letter to the French underground stating that ‘we French will have to learn to love and forgive the Germans to rebuild Europe after the war’. His humble and overtly Christian motivation was in stark contrast to that of De Gaulle, who, it has been remarked,was never accused of being too humble.

Once back in power, De Gaulle’s embrace of Adenauer in 1963 was one of mistrust: keep your enemy close to your bosom. The man who said ‘La France, c’est moi!’ also thought ‘L’Europe, c’est moi!’ He viewed the European project, which he at first opposed, as an inter-governmental institution under his leadership, rather than a project of true reconciliation, shared sovereignty and mutual accountability, as was Schuman’s original vision.

The organisers of the Europe-Ukraine forum told me they wanted ‘spiritual input from outside’, in response to my protests of incompetence in economics and politics. So during a plenary panel discussion on Thursday, when I was asked how realistic European integration could be promoted, I started with the Schuman story.

The heart of his original vision was not economics, but reconcilation, I explained. The project needed a soul, he stressed. Acknowledging that forgiveness and love was not normally the kind of language heard at this sort of forum, I said the process of reconciliation and trust building was a remarkable but forgotten chapter of European history in which Germans and French, men and women, specifically had asked forgiveness for their mutual hostilities.

Without this reconciliation, the European project would have been stranded at the start. The Europeans, starting with the French and the Germans, needed a heart change. For reconciliation did not happen automatically.

Swamp

Unfortunately that process never occurred in eastern Europe under marxism, for obvious reasons. When communism imploded, westerners rushed in with all sorts of advice as to how to build democracy and capitalism, as if trying to transplant flowers without the roots.

But the moral swamp was never drained. Forgiveness, confession and reconciliation were never considered important, and were seen as weakness. Yet spiritual foundations mattered, in economics as well as in politics. If we got that wrong we got nation building wrong, and European integration wrong, I said.

But was this a realistic approach to European integration? Schuman thought so, and so began the movement which numbers of eastern and Balkan nations today want to join. Jacques Delors, president of the European Council in 1992 also believed so. He warned: if we do not find a soul for Europe within the next ten years, the game will be over. Which may explain our present malaise, 27 years later…

So did my message land on these eastern ears? To my surprise, they spontaneously broke out into applause.

How encouraging to hear the next day Professor Frans Alting von Geusau affirm that Europe was the product of reconciliation, which was the only way for Europe to move forward.

Till next week,