(The third in a series of four addressing the persistent Russian efforts to hijack Ukraine’s history.)

If the Holodomor—the engineered famine of 1932–33—was Stalin’s attempt to break Ukraine’s body, then his campaign against Ukrainian culture, faith, and language was a calculated effort to annihilate its spirit.

The deliberate, systematic erasure of a people’s soul was perhaps the most insidious form of violence inflicted by the Soviet regime. The aim was not merely to conquer Ukraine, but to remake it in Moscow’s image, to erase any trace of a people whose history, beliefs, and traditions stood in the way of Soviet imperial uniformity.

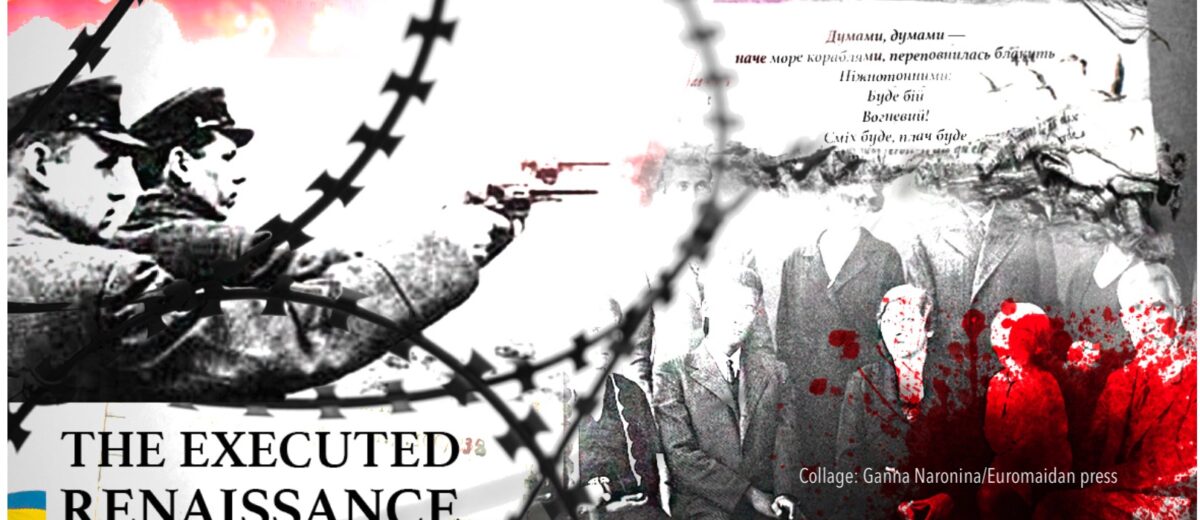

The 1920s began with promise. Ukraine, briefly independent after World War I, saw a vibrant cultural revival, a rare moment when the Soviet state tolerated national expression. During this short window, Ukrainian literature, theatre, film, music, and art flourished. But Stalin viewed this renaissance not as a cultural blossoming, but as a political threat. Independent thought, especially when expressed in non-Russian languages and narratives, was intolerable to a regime obsessed with centralised control.

Silencing voice, erasing memory

The crackdown came with brutal swiftness. Between 1933 and 1938, hundreds of Ukraine’s brightest minds—poets, playwrights, artists, and scholars—were executed, imprisoned, or forced into silence. This period became known as the Rozstriliane vidrodzhennia—the Executed Renaissance. The regime didn’t just target individuals; it targeted the very idea of Ukrainian identity.

Among the many victims were hundreds of blind minstrels – the kobzars – named after the multi-stringe kobza instrument they played and plucked, like an upright zither. The kobzars preserved and spread the historical memory of the people through music and song as they itinerated from town to town, village to village and city to city. Like Putin, Stalin wanted to impose Russian culture on all the oppressed ethnic peoples of the Russian empire. But the kobzars represented an ‘incorrigible nationalist element’ reminding the people of a narrative at odds with that of the government.

A congress was called of the ‘Folk Singers of Soviet Ukraine’ in December 1930, gathering over three hundred kobzars in the Opera Theatre in Kharkiv. Under the pretext of a trip to Moscow for the Congress of Folk Singers of the USSR, they were all ushered onto train carriages for what turned out to be a short trip to the edge of the forest. There they were lined up along freshly-dug trenches and shot dead.

What emerged in their place was a hollow, Soviet culture imposed from above: Russian in language, socialist in content, and stripped of any regional or ethnic distinctiveness. Folk traditions were suppressed, local publications shuttered, and artistic expression was reduced to propaganda. Ukraine’s cultural landscape was flattened into a grey Soviet monotone.

Equally devastating was the attack on Ukraine’s religious life. Stalin understood that faith could offer a parallel source of moral authority and community cohesion, one he could not control. For Ukraine, where the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC) were deeply woven into the fabric of national life, this was especially dangerous.

In 1946, Stalin orchestrated a sham “synod” in Lviv, forcibly “merging” the UGCC into the Russian Orthodox Church—a move backed by secret police and carried out under duress. Thousands of bishops, priests, and laypeople who resisted were imprisoned, tortured, or killed. The UAOC, which symbolised Ukrainian ecclesiastical independence, was wiped out entirely.

Churches were razed or repurposed into museums of atheism. Religious education was banned. Faith became a punishable offence. Stalin’s message was clear: loyalty belonged not to God, but to the Party. The cross was to be replaced by the red star, and public piety replaced by ideological conformity.

Cultural Occupation

Language is not merely a tool of communication—it is a vessel of memory, of identity, of belonging. Stalin’s assault on the Ukrainian language was thus another front in his campaign to obliterate the nation’s soul. Ukrainian-language schools were closed, textbooks rewritten or destroyed, and Ukrainian pushed out of public life. Even in the so-called Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the language of government, prestige, and opportunity was Russian. To succeed, to survive, Ukrainians had to become less themselves.

This linguistic colonisation was subtle yet powerful. Children were taught to see their mother tongue as backward. Ukrainian stories were replaced with Soviet myths. History itself was rewritten, with Ukrainian figures either erased or recast as regional footnotes to Russian greatness.

Erasure did not end with executions and exile. Stalin’s regime sought to colonise memory itself. Cities were renamed, erasing historical references and replacing them with Soviet icons. Traditional holidays were outlawed and replaced with Communist festivals. Schoolbooks exalted Russian tsars and generals, while Ukrainian heroes were maligned or ignored.

This was not merely cultural censorship—it was cultural replacement. Stalin didn’t just want to silence Ukraine’s voice; he wanted to ensure future generations never heard it in the first place.

Yet even under this suffocating weight, Ukraine’s soul refused to die. Faith went underground. Secret services could not extinguish worship in forest clearings or candlelit kitchens. Banned books and banned prayers passed from hand to hand in samizdat form. The diaspora preserved what was lost at home—publishing forbidden literature, recording folk songs, and nurturing national memory in exile.

This resilience is nothing short of remarkable. Despite decades of attempted erasure, Ukraine’s churches, languages, and cultural expressions have not only survived—they have revived. Cathedrals once used as granaries have been reconsecrated. Poets once silenced are now studied in schools. Ukrainian is again a language of public life, literature, and resistance.

Suffering and survival

The story of Ukraine under Stalin is not just one of suffering—it is also one of astonishing survival. The cultural and religious erasure attempted by the Soviet regime was brutal, but ultimately failed.

Today, as Ukraine faces yet another imperial assault—this time from Putin’s Kremlin—we see that the battle for the soul of the nation continues. Throughout both Tsarist and Soviet oppression, Ukrainian Christians often stood as moral witnesses. Whether through poets like Taras Shevchenko, martyr-bishops, or pastors imprisoned for faith, Christian convictions fuelled a defiance rooted not in hatred, but in truth and justice.

Christian faith prevents national trauma from hardening into hatred. Church leaders like Patriarch Sviatoslav Shevchuk (UGCC) and Metropolitan Epiphaniy (OCU), represented in last week’s Global Interfaith online meeting, call for justice but also for spiritual healing, truth-telling, and the possibility of reconciliation—though not without repentance.

War has paradoxically led to a spiritual awakening in Ukraine. Church attendance has grown, Bibles are in high demand, and people are seeking deeper meaning, often turning to faith communities for support, healing, and belonging. In a war where Russia tries to erase Ukrainian identity, Christianity helps Ukrainians remember who they are—and whose they are.

This distinguishes Ukraine’s spiritual posture from the imperial theology of the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), which has sanctified war, conquest and Russian supremacy.

Ukrainian Christians are not isolated. The war has awakened a global ecumenical movement of solidarity, where churches across Europe, North America, and beyond see Ukraine’s struggle as a test of faith, freedom, and truth. Prayer vigils, humanitarian aid, theological statements, and public advocacy are all manifestations of this faith-fuelled solidarity.

Next week, I will share ways we can show this solidarity – with a special focus on Sunday, August 24, Ukrainian Independence Day, for a Global Day of Solidarity with the Ukrainian people everywhere.

Till next week,