The fourth in a series on the spiritual revolution behind the fall of communism thirty years ago:

Long before the events of the Pan-European Picnic and the Baltic Way, and nearly two decades before the names of Gorbachev, Reagan and Thatcher appeared in global headlines, one Russian writer emerged from the Soviet gulags as the voice of truth and exposer of injustice.

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn is credited with doing more than any other critic to demolish the moral and intellectual case for Communism. In 1962, this previously unknown author published a short novel in the literary magazine Novy Mir. The provocative undertone of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich caused a sensation within the Soviet Union and around the world, leading many Soviet readers to conclude at the time that government censorship had been abolished. It described in clear, direct language the gross injustices endured daily by a simple prisoner, one of thousands in secret labour camps across the Union.

Born in 1918, a year after the Bolshevik Revolution, Solzhenitsyn grew up with a fervent belief in Marxism-Leninism. He served in World War II as commander of an artillery battalion, earning two medals for bravery. But in 1945, he was arrested for criticising Stalin and the Soviet Army in letters exchanged with a school friend, and sentenced to eight years of hard labour in a prison camp.

There he learnt the reality of the Soviet reign of terror and lies. Eight years stretched to eleven years in prisons, camps and exile. One Day was written six years after his ‘rehabilitation’ as a debt to the ghosts of his fellow prisoners, the first of numerous novels, plays, essays, poems and short stories attempting to expose the system which had incarcerated and murdered millions.

Censored

Blacklisted by the censors, Solzhenitsyn completed two big autobiographical novels: The First Circle and Cancer Ward, based on his gulag experiences and his successful treatment for abdominal cancer in Tashkent respectively. Refused for publication in the Soviet Union for their ethical scrutiny of Soviet society and of government crimes, they were smuggled to the West where they became best sellers.

Solzhenitsyn was banished from the state-sponsored Writers’ Union, and became outcast along with other independent writers who pioneered a new clandestine publication format called samizdat: poems, novels, stories and political manifestos typed and mimeographed copies secretly circulated and often sent abroad. By the late 1960’s, these writers broadened into the Dissident Movement, including academics, lawyers, scientists and engineers, unofficially led by the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Andrei Sakharov. They promoted freedom of expression and peaceful political change in the Soviet Union, and drew a global audience of readers.

In 1970, Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, “for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature”, drawing strong official criticism from the Soviets as “clearly dictated by speculative political considerations, not literary merit”. Fear of not being allowed back into his homeland prevented him from travelling to Sweden to receive the award.

Banished

Three years later, still in the Soviet Union, he smuggled abroad his three-volume masterpiece, The Gulag Archipelago, in a head-on challenge to the legitimacy of a Soviet state perpetuating wholesale incarceration and slaughter of millions of innocent victims on a par with the Holocaust. While many in the West were pursuing ‘détente’ in its relations with the Kremlin, Gulag demolished any claims to moral superiority communism had over its enemies.

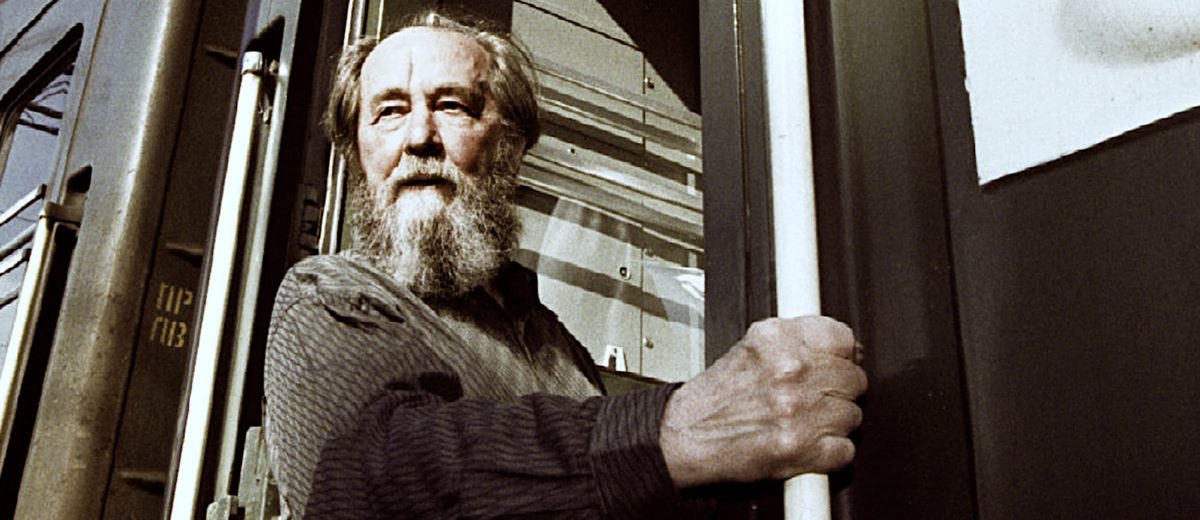

The Soviet response was to strip Solzhenitsyn of his citizenship and banish him to the West. He spent most of the next two decades in Vermont, USA, before finally returning to Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1994.

Later in life, he said: “If I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat (what I heard when a child from old people explaining the great disasters that had befallen Russia): ‘Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.’”

The day he was arrested in 1974 and put on a plane to Germany, he wrote: ‘The simplest and most accessible key to our self-neglected liberation is this: personal non-participation in lies…. It is the easiest thing to do and the most destructive for the lies. Because when people renounce lies it cuts short their existence. Like a virus, they can only survive in a living organism.’

This exhortation to refuse to live the lie was to be echoed powerfully by the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel in the years immediately following Solzhenitsyn’s exile, nurturing a simmering spiritual revolution which eventually ignited the Velvet Revolution.

While his support of Putin’s Russian nationalism and opposition to Ukraine’s independence have raised questions about his final legacy, Solzhenitsyn’s heroic unmasking of the horrors of the Soviet regime was vital in communism’s downfall.

Till next week,