Politics, as everybody ‘knows’, is a dirty business. No place for Christians, so the argument goes.

Or should we say that’s the very reason why Christians should be involved?

This week in Brussels, Romkje and I have been coaching young aspiring politicians as part of a programme of the European Christian Political Movement wrestling with this sort of question. Most come from eastern Europe, including Ukraine, Moldova and Armenia.

However, reports of Russian military manoeuvres in the Black Sea and on the borders of Ukraine have overshadowed the week as they threaten to swell into a full-scale invasion of a country that has only ever known three decades of independence from its overbearing neighbour.

The danger of war on Europe’s eastern front has also dampened any celebration of the Maastricht Treaty, signed thirty years ago this week in the southern Dutch city to create a politically-unified European Union. What had started as the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 expanded to the European Economic Community in 1956 and then the European Union in 1992, embracing the idea of a European citizenship and a common currency.

After the then French president François Mitterrand convinced Germany’s chancellor Helmut Kohl to make Germany’s reunification more palatable to its neighbour by sacrificing the D-mark on the altar of European unity, francs, lire, guilders and other currencies were also exchanged for euros in all twelve member countries except Denmark and Britain. This followed months of negotiation, resulting in a compromise between countries that wanted a full union and those who wanted a looser relationship.

Expansion

Since 1992, and with the collapse of the Soviet Union and its hegemony of eastern Europe, the EU grew to 28 members, including the formerly Soviet Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, other Warsaw Pact members Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia, and former communist Yugoslavian nations of Slovenia and Croatia.

Although as we know all too well, Brexit reduced the total EU membership to 27, nineteen other nations use the euro now. The loss of Britain is just one of several challenges facing the union on its thirtieth anniversary. Populism, climate change, pandemic and energy supplies are just some of the hurdles to clear as the EU faces the future as it continues the daunting task of ‘building on the go’ (sometimes likened to constructing an aeroplane while in flight).

Expansion eastward has far exceeded the founding fathers’ expectations – yet has sown the seeds for the greatest European military crisis in a generation. For Vladmir Putin, the collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest disaster of the twentieth century. He has greatly resented the flight to the west. As we watch, he is trying to reverse history. Has he not in effect already annexed Belarus and Kazahkstan with ‘benign’ military occupation while all eyes have been on Ukraine?

Galvanised

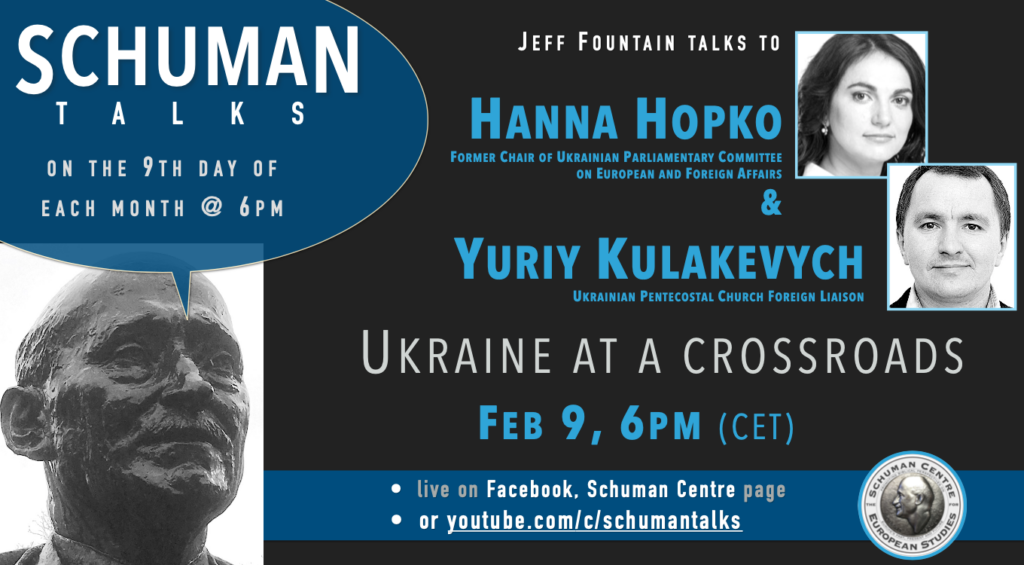

This week I had a most invigorating Schuman Talk with two Ukrainian insiders, politician-activist Hanna Hopka and church leader Yuriy Kulakevych, about the current situation. Hanna has no illusions about Putin’s aims, but promises strong resistance from a nation with stronger resolve than ever not to become puppets once more of the Moscow regime – even among the minority Russian-speaking population.

Yuriy reminded us of how the 2014 Maidan revolution of dignity and freedom had made the Church aware that it belonged in the city centre. Much of the Church – from Orthodox to Pentecostal – had been galvanised to pray and work together for justice and freedom and against political repression and corruption. Many Christians had been recently voted in to government or mayoral roles. Church leaders had realised the Bible had much to say about the public square, not just about church life and personal devotion.

Ukraine is a nation at a crossroads. Much is at stake for the future of Europe in her future. The stirring of understanding among Ukrainian church leaders about the role of the church in society is rather unique on a national scale in Europe. We in the west could learn much from their example.

The young people we are coaching this week in Brussels are engaged in one of the very few programmes I know equipping Christians to engage in political life anywhere in Europe. Why is this so? Why are our theological institutions only focused on training church leaders but not leaders for society? Do we mean to say the Bible has little to say about life from Monday to Saturday? Do we want to imply that the Gospel is irrelevant for daily life?

We may well think politics is a dirty business unfit for believers, or that the European Union is a hot-bed of humanistic activism bent on undermining godly values. But is abandoning the public square really the way to ‘see God’s will being done’ in Europe?

Thank God for these young enthusiasts eager to be trained for public witness!

P.S. Watch this challenging interview here.

Till next week,