The 20th and last in a series of draft chapters for a popular-style illustrated coffee-table book about how the Bible has shaped so many facets of our western lives. Feedback is welcomed.

THE BIBLE, WINE AND BEER

“Come quickly!’ cried Dom Pérignon to his fellow Benedictine monks, “I’m drinking stars!” The cellar master of Hautvillers in the Champagne region of France had just tasted the outcome of his wine-blending experimentation culminating in the accidental discovery of sparkling Champagne.

The exhilaration of ‘drinking stars’ he and his brothers experienced that day is shared globally today by those with something to celebrate: from newly-weds to Formula One champions. The name ‘Dom Pérignon’ stands for one of the the finest vintage Champagnes on the market today.

That Pérignon the monk (1637-1715) was experimenting with wine-making procedures should not be surprising. Wine and beer production in Europe since the early Middle Ages was closely intertwined with the story of the Bible, monks and monastic communities.

Wine and beer have existed from the earliest times of civilisation, long before Christianity ever emerged. While the Bible warns often against drunkenness, the theme of wine and vineyards figures prominently in both the Old and New Testaments. Wine was a gift from God to gladden men’s hearts. Jesus turned water into wine at a wedding and was himself accused of being a winebibber. He told numerous parables involving vineyards and described himself as the true vine, his disciples the branches.

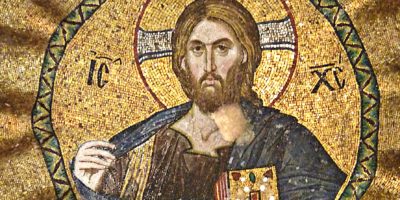

Wine was an essential part of worship rituals. When Jesus turned the Jewish Passover Feast into the Christian ritual of the Eucharist, or the Lord’s Supper, he gave later generations of his followers reason to plant vineyards wherever they would take the gospel. Wine was an essential element in the sacrament of communion, as Paul wrote (I Cor. 11:25): “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.”

Early church fathers viewed wine as affirming the goodness of God’s creation, in contrast to the gnosticism of the day which taught that matter was evil but the spirit-realm was good. Although the Romans had earlier introduced wine-growing in the Rhone valley, Martin of Tours (316-397) pioneered vineyards in western France, later becoming the patron saint of wine-makers. Benedict of Nursia (c.480-547) prescribed a daily rhythm of prayer and work, ora et labora – plus one herminia of wine daily (about 275 cc). Benedictine monasteries brought new order and spiritual discipline into the chaos resulting from the collapse of Pax Romana. Wherever the Benedictine monks settled they introduced wine: in Burgundy, Bavaria, Franconia, the Rhineland, Thuringia, Prussia and Switzerland.

Early in the second millennium, the Cistercian reform movement revived the original Benedictine emphasis on agricultural work and established many wines famous today, such as the Nuits-Saint-Georges, the Clos de Vougeot, Riesling wines from the Rhine region and those from the Côte d’Or. One branch of Cistercians, originating from La Trappe Abbey in Normandy, became famous for their beers. Today twelve monasteries in Europe and the United States still brew Trappist beer.

In northern Europe, where grapes could not so easily grow, beer provided the staple drink. Drinkable water was not readily available until more recent times. Water-borne illnesses such as cholera were common. Wine and beer were safer to drink because the alcohol and fermentation process helped to kill dangerous microorganisms. Prior to the Reformation, monastic communities provided breweries for the cities. Around 1500, for example, Utrecht in the Netherlands had twenty-eight monasteries within the city walls and twenty-four breweries.

The Reformers, such as Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, and later on the Puritans and Wesley, all believed wine to be a gift from God. Katharina, Luther’s wife, was a former Cistercian nun who brewed her own beer, while her husband was paid in bottles of wine for his preaching. Despite this, the Reformation in northern European countries, and later the French Enlightenment and Napoleon’s conquests, closed or even destroyed many monasteries, causing many monastic vineyards and breweries to be privatised.

English Puritans, German Pietists and French Huguenots, all Protestants emigrating to the American colonies, failed in their attempts to plant vineyards there. Imported wine became unaffordable for ordinary folk who took to rum and whiskey. In time, drunkenness led to the temperance movement focused on abuse of spirits, not wine and beer, but which in turn became a prohibitionist movement against all alcohol, largely supported by evangelicals in America and Britain.

In Ireland, widespread drunkenness due to gin and whiskey also disturbed Arthur Guinness, who was influenced by the ministry of John Wesley and who founded the first Sunday School in that nation. He believed God told him in prayer to ‘make a drink that will be good for men’. The result was the lower-alcohol Guinness dark stout beer with so much iron that people felt quickly satisfied and so drank less.

Whatever our stance on drinking alcohol, we cannot deny the influence of the Bible and the movements spreading Christianity in Europe on the development of something as seemingly secular as wine and beer.

Till next week,