Why are we Christians not usually more positive about life? about the future? about people who are different from us? If we believe in a sovereign God who is working out his purposes in history, why are we so quick to adopt gloomy end-time scenarios or even embrace conspiracy theories multiplying these days via social media?

During online lectures with seminary students in Belgium last week, I happened to touch on two examples when we or our forebears got it all wrong. One was the First World Missionary Conference held in Edinburgh in 1910. Most if not all of the delegates were resigned to the expectation that Africa would become overwhelmingly Muslim over last century.

Granted, the number of Muslims living in sub-Saharan Africa rose from around eleven million in 1900 to approximately 234 million in 2010. Yet Christian growth was even faster, soaring over seventy-fold from about seven million to over 600 million today. Six-hundred-million! That is more than the whole population of the European Union. (See World Christian Database).

The other instance I shared with the students was the Cold War era when Marxism was widely viewed as the anti-Christ ideology that would dominate the world. I grew up in that era when Hal Lindsay’s book, The Late Great Planet Earth, sold in its millions, convincing huge numbers of Christians we were living in the end-times when things would get worse and worse. Communism would be with us for ever and ever amen.

The dramatic events of 1989 proved all that to be wrong. The ‘Miracle of Leipzig’ I wrote about recently and the triumph of truth over lies helped us dare to believe in a Future Great Planet Earth.

Groping in the gloom

Yet COVID, climate change, terrorist beheadings, fake news, fraying democracies, polarised societies, conspiracy theories about vaccines and chips, and social media with their addictive algorithms have some of us groping once more around in the gloom.

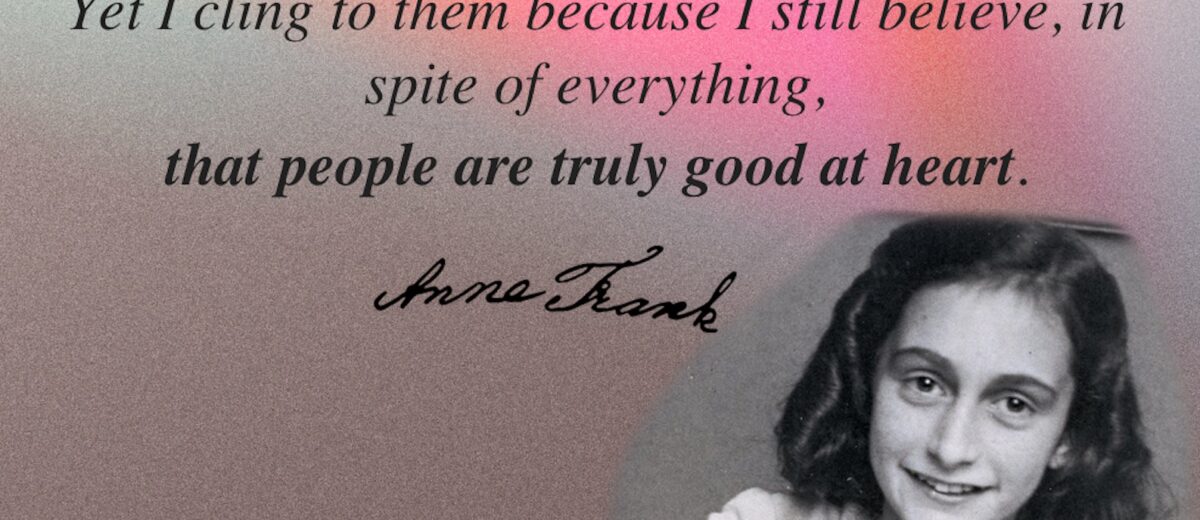

Of all people, Christians have reason for hope. Yet sometimes the most hopeful perspectives come from non-Christian sources. Anne Frank, the Jewish teenager who kept a diary during World War II in her Amsterdam hiding place before being railed away to die in the gas chambers, wrote: “It’s a wonder I haven’t abandoned all my ideals, they seem so absurd and impractical. Yet I cling to them because I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.”

Dutch journalist Rutger Bregman argues this point persuasively in his best-seller Humankind (the original Dutch title literally translates as Most people are decent). Was Thomas Hobbes right when he argued in Leviathan that raw human nature was brutal, selfish, violent and fearful? Countless authors have expanded on his view that humans were rational, self-serving individuals, from William Golding in Lord of the flies to Richard Dawkins in The selfish gene. Yet these authors’ ideas have been discredited in recent years, says Bregman, whose real-life story of six Tongan youths stranded on a rocky island in the Pacific for sixteen months demonstrated solidarity, courage and hope, unlike Golding’s fictional ‘classic’.

That story and many others Bregman relates support the notion of Jean-Jacques Rousseau that humans are basically good, peace-loving, cooperative beings. Here we have the roots of the tensions we see all around us today between conservatives and progressives, realists and idealists. In theological terms, it is the age-old tension between Augustine (‘we sin because we’re sinners’) and Pelagius (‘we’re sinners because we sin’).

Grace and goodness

Theologians through fifteen centuries have not fully resolved this tension. Western theology has tended to follow Augustine, while Pelagius’ ideas resonated more with Eastern theologians like Origen and Chrysostom. Celtic Christianity, whose spread through Ireland and Britain we traced with the students, reflected more oriental traits than western, more John than Paul; grace was given by God to liberate the goodness planted at the heart of life. After the Celtic church was assimilated into the Catholic Church at the Synod of Whitby in 664, much of the rich Celtic legacy was sadly lost to the west.

Bregman’s thesis is a challenge to us as Christians to think again about human nature. As are the claims of Swedish professor Hans Rosling (about whom I have written earlier) that human society has never been in better shape than now.

Both Bregman and Rosling point to the disservice to us of the news media, which Bregman compares with a super-addictive drug causing ‘a misperception of risk, anxiety, lower mood levels, learned helplessness, contempt and hostility towards others’. News brings the abnormal into our lives, amplifying the negative, attuning us to the bad.

In these days of frenzied social media activity, we do well to heed Pauls’ encouragement to fix our thoughts ‘on what is true, honourable, right, pure, lovely, admirable, excellent and worthy of praise’ (Phil. 4:8).

Till next week,