Last Sunday at 4.30am, my deep slumber was rudely disturbed by honking car horns.

Half-awake, I drew the curtains to glimpse a convoy of cars draped with Syrian flags driving through the centre of Amsterdam. Something dramatic obviously had happened in Damascus.

A quick check of the headlines on my mobile confirmed that, while I was sleeping, the Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad had been forced to flee. With huge ramifications. Not only for the millions of Syrians now free of his oppressive regime. Nor for the millions of Syrians forced to flee from their homeland over past decades of Assad rule. But also for the global geo-political balance. What the immediate future holds for all Syrians is still too early to say, but for now Syrians everywhere are glad to be rid of their dictator.

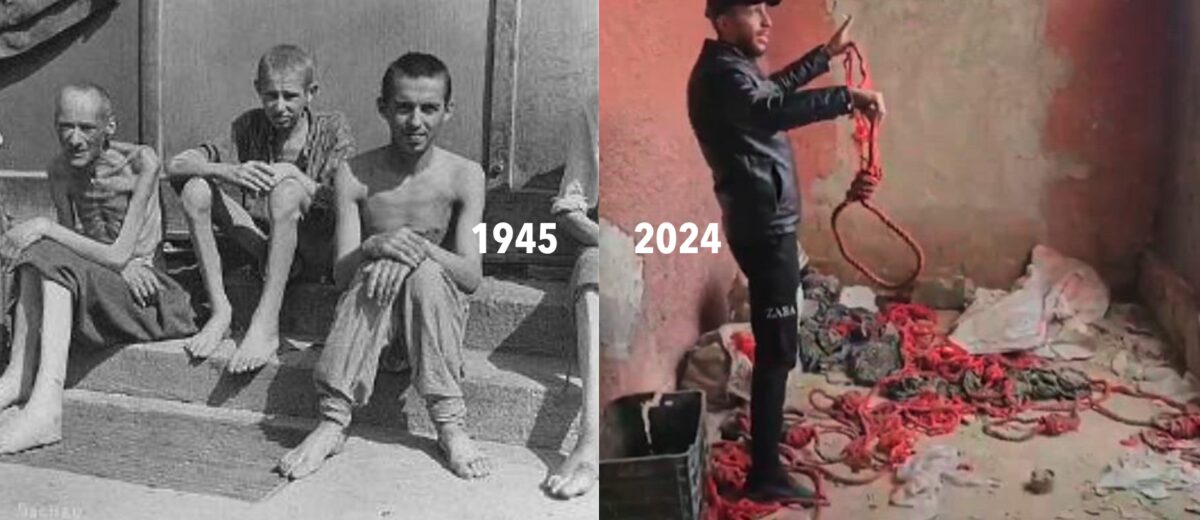

Images on our television screens of rejoicing street crowds and emaciated prisoners triggered for me memories of films and photos after the collapse of Nazi terrorism in 1945. Now, as then, euphoria is mingled with horror at the revelation of the gross violations of human rights under a ruthless dictator.

Then, nearly eighty years ago, those images had galvanised global resolve to prevent such injustices from ever happening again on such a scale. Leaders from Europe, America and other parts of the world began working together to establish a new world order out of the ruins of World War Two. The cornerstone of this order was to be the recognition of the inviolability and inalienability of human rights as the basis of peace and justice in the world.

Unnoticed

Last Wednesday, as further revelations of the grim reality of Assad’s notorious prisons came to light, Human Rights Day should have been spotlighted everywhere. Sadly this anniversary of one of the world’s most groundbreaking global pledges went largely unnoticed, overshadowed by the immediate headlines.

For it was on December 10, 1948, when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris, enshrining the inalienable rights for all – regardless of race, colour, religion, sex, language, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.

Surely this landmark deserves the recognition, support and promotion by Christians worldwide. Unfortunately some Christians have an aversion to ‘human rights’ as being hijacked by the ‘woke’ agenda. Indeed, the Roman Catholic Church even anathematised the concept of ‘human rights’ under Pope Pius IX in reaction to the anti-church policies of the French Revolution and its Declaration of the Rights of Man.

Yet the very concept of human rights is biblical in origin, rooted in the understanding that each person was created in the image of God and thus had dignity and sanctity. Every one of the Declaration’s articles can be undergirded by scripture. Without the biblical foundations, there are no grounds for human rights. If humans are merely the end product of a purely materialistic, chance process of evolution favouring the survival of the fittest, who can justify the ‘rights’ of the weak and vulnerable to protection?

‘Christian forces’

The very existence of the UDHR is the fruit of the concerned efforts of Christians, Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant, without whose initiative no UN commission would have been established to draft such a document. Under the influence of French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, one of the drafters of the UDHR, and mentor to Pope Paul VI, the Catholic Church eventually embraced the cause of human rights during Vatican II in the 1960’s.

Another drafter of the document was the Lebanese Orthodox theologian, academic, diplomat, philosopher and politician, Charles Malik (whose son Habib I interviewed two years ago). Asking himself, ‘where do human rights come from?’, Malik senior asked rhetorically whether they were conferred by the state or the UN; or if they belonged to the essence of being human (inalienable), and therefore grounded in a Supreme Being who, ‘by being Lord of history, could guarantee their meaning and stability?’

Prominent non-Christians also helped shape the declaration, including a French Jewish lawyer, a Chinese philosopher, an Indian feminist, a Chilean socialist, an Italian liberal, the agnostic Aldous Huxley and Mahatma Ghandi. Yet the US Secretary of State, John Forster Dulles, judged that ‘Christian forces’ had been primarily responsible for giving the UN Charter a ‘soul’ in the commitments to human rights.

The roots of human rights actually go back much further than the Enlightenment, to minority Christian traditions including Mennonites and Baptists, among the first to articulate the cause of freedom of religion and conscience.

Human rights remain the cornerstone of the international order presently being challenged by autocrats and anti-democrats like Putin, who shows scant regard for the lives of the 700,000 Russians and their families he has wrecked by his own imperial ambitions. Not to mention the lives of millions of Ukrainians.

How we’d love to be woken up by honking horns announcing the downfall of that tyrant!

Till next week,

Dear Jeff,

Thank you for bringing all that to the Light again.

So good to know where Christians have initiated & helped The World to enshrine God’s Highest Ways of doing things for people, giving them the hope of better lives, dignity, respect and justice.