I learnt a new word this week: agnotology, the study of the deliberate propagation of ignorance.

Agnotology comes from the Greek work agnosis, meaning ‘not knowing’ or ‘ignorance’, and ontology, which deals with the nature of being.

The word was coined 25 years ago by researchers who discovered a secret memo revealing the tactics of the tobacco industry to spread confusion about smoking causing cancer. “Doubt is…the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the mind of the general public,” read the memo. “It is also the means of establishing a controversy.”

Sowing doubt, creating controversy and spreading ignorance has also become deliberate political strategy. A classic example was the politically motivated doubt sown over US President Barack Obama’s nationality for many months by opponents until he revealed his birth certificate in 2011.

Ignorance is often spread through ‘balanced debate’, promoting ‘two sides to every story’, and the popular idea that ‘experts disagree’. Tobacco firms and climate change deniers use ‘science’ to argue against the scientific evidence. The goal is to create a false picture of the truth, spreading ignorance.

The internet and social media – where everyone is an ‘expert’ – have become powerful conduits of deliberate confusion, agnotologists tell us. During recent US presidental election campaigns, for example, candidates have proposed easy solutions to followers that were either unworkable or unconstitutional. Sowing doubt about election procedures and outcomes, and the deliberate creation of controversy, has shrouded American democracy in confusion and mistrust.

Breakdown

The COVID-19 crisis has been yet another example of how doubt, confusion and ignorance have been deliberately (or often unwittingly) spread by anti-vaccination parties. As our nations begin to take first cautious steps towards ‘normality’ after what has seemed an interminable lockdown, the world we are returning to is one where democratic institutions are increasingly more fragile.

Jonathan Chaplin’s new and timely book, Faith in democracy, warns that we are facing a general breakdown of our democratic institutions because of a widespread ignorance about the larger moral purpose of democracy: to seek the common good and public justice for all. Even in Britain, over half the respondents to a recent survey asking if Britain ‘needs a strong ruler willing to break the rules’ said yes; less than a quarter said no.

Evangelical Christians ought to be the first to be committed to seeking truth, standing for truth and spreading truth. Sadly, as Jonathan points out, evangelicals have been among the first to embrace conspiracy theories, aggressive populism and political figures promoting ‘illiberal democracy’.

Cancerous

My current research on evangelical attitudes towards the European Union is revealing widespread ignorance about how and why Christians should be engaged in political issues. One leader told me this week that evangelical ignorance was cancerous, and was ‘really, really harming our democracy’. Christians were not vaccinated against this cancer, he said.

At least three influences in evangelical streams can be seen promoting such ignorance. One is the apolitical tradition, strong in non-conformist circles, holding that the gospel is really only about saving souls; socio-political engagement is a distraction to the core task. This understanding of the gospel neglects the all-encompassing impact of the redemptive work of the cross into every area of life impacted by sin – which is every area of life. As Abraham Kuyper famously stated it, just 800 metres from where I sit to write: There is not one square inch of human life where Christ, who is sovereign over all, does not say ‘mine!’.

A second stream is focused on popular eschatologies which presume that Christian political engagement is futile as Europe is predestined and doomed to fulfil an anti-Christ/beast role in end-time scenarios. The Left Behind book and film series promoted this perspective and continues to influence some circles.

A third current calls for the ‘taking back of our country for God’, Christian nationalism in various forms. The Seven Mountain Strategy is one expression of this movement, which, seeking to replace a dominant ‘godless and corrupt’ elite with a ‘righteous’ one, falls short of seeking public justice for all and the common good of all.

Next to recommending Jonathan’s book for summer reading, let me suggest two other opportunities to address this ignorance. One is the Summer School of European Studies, July 12-16, in Amsterdam (see below). The other is the three-year, part-time masters degree programme in Missional leadership and European studies, designed for those engaged in churches, mission agencies or community projects, or who wish to work in journalism, politics, law, advocacy, education or civil service.

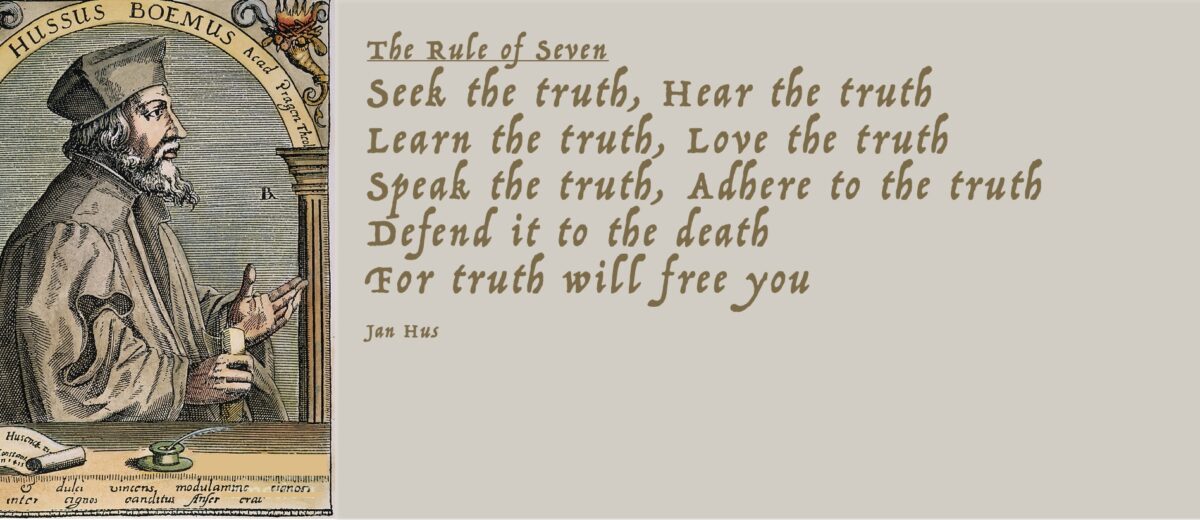

May we heed the counsel of the Czech reformer, Jan Hus, to become seekers, hearers, learners, lovers, speakers, adherers and defenders of the truth.

Till next week,