My Christmas reading has offered a surprising perspective of hope for Ukraine from a new book about the 17th century Dutch painter, Johannes Vermeer.

Vermeer lived, worked and painted in the newly liberated Dutch Republic after an eighty-year struggle for sovereignty, cultural freedom and national identity against Spanish imperial rule.

Andrew Graham-Dixon’s book describes in sometimes gruesome detail the desperate resistance of the Dutch over several generations against the repressive Habsburg rulers as he sets the context to Vermeer’s work.

His insights are startling, shedding totally new light on the spiritual meaning of the popular Dutch painter’s work, including Girl with a pearl earring and The Milkmaid. I plan to write about this soon but will focus here on the relevance of this phase of Dutch history for Ukraine. (For the curious and impatient, get your preview here.)

Meanwhile, let’s explore the historical and moral parallels between the struggle of the Dutch people for independence from Spanish rule in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and Ukraine’s contemporary struggle for sovereignty against Russian aggression now. While separated by time and context, both conflicts illuminate enduring questions of imperial domination, national identity, religious freedom, international law, and the legitimacy of resistance.

Unplanned

No one actually set out to create the Dutch Republic. It was ‘the unplanned result of a bitter and bloody war, marked by numerous atrocities, most of which were motivated by religious intolerance or outright sectarian hatred’, the author writes. Yet – here’s the encouraging bit – even before hostilities ended in 1648, the Republic had become the global leader in fields of trade, finance, government, shipping, exploration, astronomy, cartography, publishing, international law, toleration and freedom. As the Republic waxed in power and wealth, so Spain’s empire began to wane.

The trouble began in the 1550’s when the Catholic Spanish Habsburg rulers over the Low Countries – today’s Belgium and the Netherlands – tried to turn back the tide of the Reformation by persecuting Lutherans, Calvinists and other Protestant dissenters. King Philip II sent the Duke of Alva with an army to crush rebellion. He imposed crippling taxes. He set up an inquisitional Council of Troubles to sentence suspected heretics to death.

Some 60,000 refugees fled to Germany and England. Alva’s arrogance and tyranny bred determination to resist. William of Orange, who had served loyally in the Habsburg court, was no Protestant radical. Yet appalled by Alva’s ruthlessness, he called for widespread resistance. The Dutch national anthem, sung at international sports events, still commemorates his rebellion.

Alva responded with more brutal reprisals intended to quench resistance. He laid siege to towns and cities. Mechelen. Antwerp. Zutphen. Haarlem. Naarden. After surrender, he sent his troops in to rape, pillage and murder. Whole populations – men, women and children – were massacred.

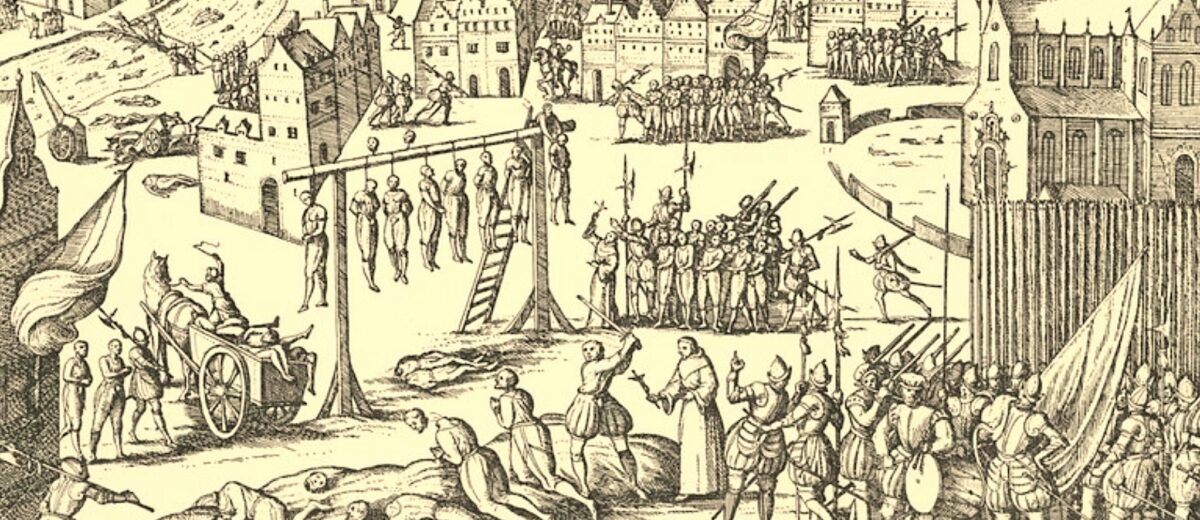

The illustration above shows bodies dangling from gallows erected in the Grote Markt of Haarlem. Such acts of terror were designed to break the morale of the rebels. Instead it galvanised their resolve to fight on for their freedom – of conscience, of worship, of self-governance and from fear of tyranny. They were inspired by Calvin’s theology which viewed resistance not as rebellion, but as faithful obedience to a higher moral order. Not only was it permissible to resist tyranny; it was a Christian duty. Authority that systematically violates justice forfeits its moral legitimacy. Resistance became legitimate when it sought not domination, but the protection of human dignity and communal life.

Justice

The Dutch Revolt lasted eighty years, marked by internal divisions, military setbacks, fragile alliances, and repeated attempts at negotiated settlement. Foreign powers hesitated to support the Dutch, fearing destabilisation or escalation. Yet this unplanned revolution was not merely a national origin story; it is foundational to European ideas of sovereignty, freedom of conscience, and limits on imperial power.

International law, pioneered by Hugo Grotius, emerged from this context. Grotius articulated principles grounding political authority in justice rather than mere power. These ideas later informed the 1648 Peace of Westphalia and the modern international system consolidated after World War Two, right now under threat from both Moscow and Washington.

The parallels with Ukraine’s resistance are striking. Dutch identity was dismissed as provincial rebellion against a universal Catholic empire. Ukrainian identity has been dismissed as artificial, regional, or a Western invention. Both struggles sought the legitimacy of local language, national culture, self-rule and true memory.

The Dutch Revolt offers a morally instructive lens through which to evaluate Ukraine’s struggle today. If the Dutch were justified in resisting Spain, who can deny Ukraine’s right to resist Russia?

The emergence of the Dutch Republic birthed many features of the modern era. What might Ukraine’s victory over Russian tyranny and oppression mean for our future? For this is not just Ukraine’s struggle. Ukrainian success or failure will determine the international order for generations to come.

Like it or not, we are all involved.

Till next week,

kwy7iw