Shortly after crossing the border between Scotland and England on the east coast, you can catch the first glimpse of the tiny island called Holy Island, or Lindisfarne, which profoundly influenced the culture and worldview of a fledgling England late in the first millennium.

The silhouette of castle ruins on the island’s rocky bluff is echoed by the fainter outline on the horizon of a more ancient fortification on the mainland. This is Bamburgh, the former home of King Oswald, who invited monks from the Celtic monastery of Iona to begin a mission in his realm of Northumbria in 635.

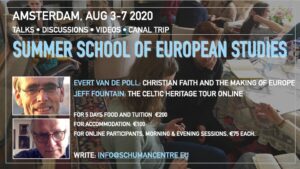

Our international group of online-pilgrims following our first virtual Celtic Heritage Tour will ‘gather’ in Dublin on August 3 for the first of five days exploring the influence of the gospels in shaping Ireland and Britain’s story – and from there, the story of western Europe. After a tour of Ireland visiting key sites in the story of Patrick, and several sites of monastic communities where literally thousands of young people trained for missions, we cross to Scotland and journey with Columba to the isle of Iona, a springboard for the evangelisation of Scotland. After a brief tour of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh will introduce us to the rich and sacrifical history of Scotland, from early Celts to modern missionaries like David Livingstone and Eric Liddell, we follow St Aidan’s journey from Iona to Lindisfarne in response to the king’s invitation.

Turning onto the coastal road to follow the signs to Holy Island, which is cut off from the mainland twice daily by a tidal channel over a kilometre wide, we drive over a causeway marked by a row of wooden stakes across the sands to and from the island.

Cultural landmark

While today the island only has about 160 residents, over 650,000 visitors come each year from all over the world: bird-watchers, walkers, anglers, artists, writers, photographers – and of course, pilgrims. The statue of Aidan close to the ruins of the Lindisfarne Priory recalls the Celtic saint who crossed the sands countless times to preach the gospel in the length and the breadth of Northumbria, often with King Oswald translating for him from Irish Gaelic into Anglo-Saxon or Old English. Little remains of Aidan’s original monastery, the priory having been founded in the 11th century after the Norman invasion, and the castle dating from the 16th.

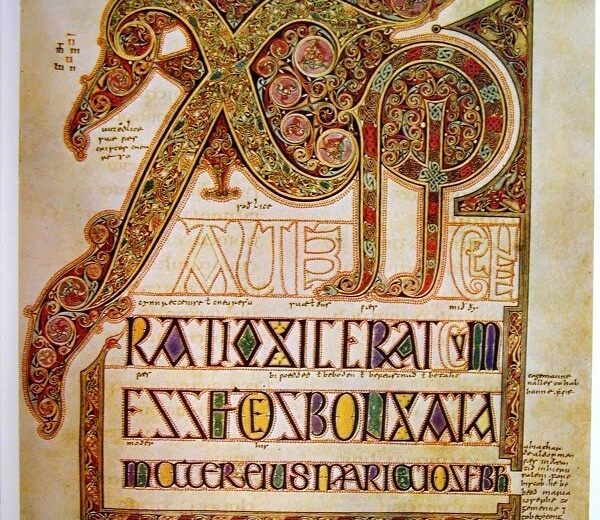

The very first Viking raid on British soil took place on this island in 793, leading to invasion and settlement, and the eventual abandonment of Lindisfarne by the monks in 875. Yet the literary legacy of Aidan’s community includes what has been called ‘one of the greatest landmarks of human cultural achievement’. For the Lindisfarne Gospels are what travel writer William Dalrymple describes as ‘one of the world’s greatest works of art in book form’, and ‘a crucial document in the history of Western Christianity’. The Sunday Times called it ‘the book that made Britain’.

The Lindisfarne Gospels were created on Holy Island by Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne, 1300 years ago, to honour the memory of Cuthbert, born the year Aidan settled on Holy Island. As Cuthbert grew up and entered monastic life, Aidan sent the brothers Cedd and Chad on successful apostolic missions to the East Saxons (Essex) and the Mercians (the Midlands). Cuthbert became prior at Lindisfarne in 664, the year of the fateful Synod of Whitby when Rome demanded–and acquired–dominance over the independent and decentralised Celtic church.

Cuthbert the bridge-builder accepted the Whitby ruling. He stressed unity with diversity as he worked to reform the community and gained a widespread reputation as a holy man and worker of miracles. When the island was abandoned in face of the Viking threat, Cuthbert’s body and the Gospels crafted in his memory began an eventful journey ending 120 years later in Durham.

The Gospels richly embody Cuthbert’s emphasis on diversity in unity. Breath-taking in detail, colour and ornate design, the Gospels weave elements of book-making, ornamentation, script, illustration, theme and symbolism not only from the Irish Celtic and Roman traditions that were fused at Whitby, or from the scribe’s Anglo-Saxon roots. Experts have also identified elements from Coptic, Byzantine, Oriental and British Celtic sources.

The story of Lindisfarne and of the Gospels inspire many today to pray and strive towards a weaving together of God-given strands of spirituality which over time have become separated.

You can still join us to learn more about this inspiring missions movement and its influence as we ‘drive’ further down the English coast to Durham, York, Lichfield and Cambridge, and eventually to London and Canterbury.

To register, write to info@schumancentre.eu. Instead of the €1500 plus fee for travel, accommodation, food and museum entry, you only pay €75.

You can also join Evert Van de Poll’s 10-hour lecture series on Christian faith and the making of Europe each morning on the same days, also for €75. Or attend the Summer School of European Studies live in Amsterdam with both morning and evening series, plus afternoon activities of museum visits, canal boat tour and more for €200 (accommodation €100).

See you in Amsterdam? or online?

Till next week,