Only two days into our Celtic heritage Tour, our group of 14 pilgrims is already deeply impacted by the depth and freshness of this significant stream of Christianity largely lost and forgotten by most of the Christian world for centuries.

Only two days into our Celtic heritage Tour, our group of 14 pilgrims is already deeply impacted by the depth and freshness of this significant stream of Christianity largely lost and forgotten by most of the Christian world for centuries.

Half of our group has previously experienced the Continental Heritage Tour. Now we are exploring the prequel to that story. For the Celtic movement that germinated in Ireland had a vital role in the conversion of the British Isles and so much of what we call Western Europe today.

While the first official Roman Catholic mission to Britain was as late as 596, led by Augustine of Canterbury, Patrick had crossed the Irish Sea to evangelise his former captors already in 432.

His own family had been part of a British church planted before Rome ascended to assume the paramount position within Christianity.

Some have suggested that at least some churches in Britain could have been the result of mission via the Galatian connection. That is, the people group in central Asia Minor Paul wrote to were Celtic, (Gelats=Celts) and despite the apostle’s admonitions to them for being ‘foolish dimwits and slow-learners’, their evangelistic efforts may have worked their way up through a Celtic network all the way to Britain.

Similarities

The Celtic church had significant differences with Roman expressions of Christianity but striking similarities with Coptic, Ethiopian, Syriac and Armenian artwork and manuscripts.

One difference was that, unlike Rome, which championed Peter and Paul as their apostles with links to the Eternal City, the Celts emphasised John’s stress on love. John’s disciple Polycarp in turn had discipled Irenaeus, who became bishop of Lyons in Celtic territory. This suggests another avenue whereby the church could have spread up through Gaul and across to Britain.

What is clear is that when Patrick returned to Ireland to begin his mission, the communities he planted were distinctly different from those in the Roman empire. There were no cities in Ireland and Patrick and his disciples planted rural monastic communities modelled on those of the Desert Fathers in Egypt.

We have been visiting some of these early communities over the past days, settlements of sometimes up to 3000 people, and which lasted for a thousand years. While marauding Vikings ravished many of the monastic settlements in Ireland, Scotland and England, they themselves eventually were Christianised. Some of their descendents even joined such communities. A second wave of Viking offspring, the Anglo-Normans, brought another bout of mayhem and destruction in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Finally, Henry VIII’s Protestant forces ransacked and abolished the remaining monasteries, now under Roman authority as Benedictine, Cistercian or other orders. At Glendalough, for example, his soldiers cast all the treasures of manuscripts, liturgical vessels and art into the lake, bringing to a tragic end a millennium of Celtic creativity.

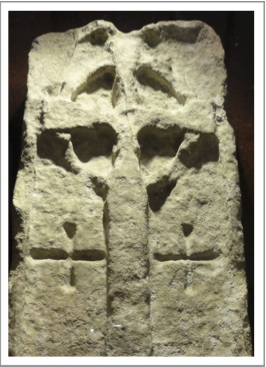

It was left to Oliver Cromwell’s troops to rampage through Ireland in the 17th century smashing many of the remaining high crosses and demolishing many ancient buildings.

Building blocks

The Celtic legacy however had spread across the continent from today’s France through to Italy and Austria. Their monastic settlements became building blocks for an emerging civilisation shaped by Christian values, many growing into cities including St Gallen, Bregenz, Luxeuil and Bobbio. The Irish became known as the intellectuals of Europe, ‘disciplers of nations, teachers of kings’.

Ian Bradley, one of many authors seeking to revive Celtic spirituality to help equip church for today’s challenges, writes:

‘Celtic Christianity does seem to speak with almost uncanny relevance to many of the concerns of the present age. It was environment-friendly, embracing positive attitudes to nature and constantly celebrating the goodness of God’s creation. It was non-hierarchical and non-sexist, eschewing the rule of Diocesan Bishops and a rigid parish structure in favour of a loose federation of monastic communities which included married as well as celibate clergy and were often presided over by women.’ (The Celtic Way, p. viii)

We look forward to learning more about this inspiring movement and its influence as we cross over to Scotland and drive down the English coast to Lindisfarne, Durham, York and Cambridge, and eventually to London and Canterbury.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,

Really enjoyed your article