George Frideric Handel was only 28 years old when he was commissioned by the British royal family to compose a special sacred work to be performed in St Paul’s Cathedral in thanksgiving for the end of the first world war in 1713.

George Frideric Handel was only 28 years old when he was commissioned by the British royal family to compose a special sacred work to be performed in St Paul’s Cathedral in thanksgiving for the end of the first world war in 1713.

No, that is not a typo. For the world’s first global war took place a full two centuries before what we call World War One erupted in 1914.

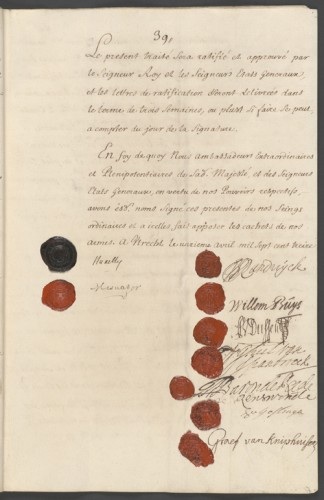

Handel’s Utrecht Te Deum reminds us that the Dutch city of Utrecht was chosen for the peace congress which brought the warring nations of the newly-formed Great Britain, France, Savoy, Portugal, Prussia, the Dutch Republic and Spain around the table. The congress turned the city upside down for over a year until the Treaty of Utrecht was finally signed in April 1713, 300 years ago this month.

This was the first peace ever achieved through diplomacy, and Utrecht served as a kind of UN headquarters. Like a year-long Olympic Games, the congress brought in thousands of temporary inhabitants, from civil servants and negotiators to theatre performers and prostitutes, each nation setting up their own headquarters in various stately mansions and stadskastelen within the old city.

The treaty concluded the War of Spanish Succession fought between two alliances of European powers, triggered by the failure of the Spanish Hapsburg king, Charles II, to produce an heir before he died in 1700.

The French king, Louis XIV, saw his chance to expand his domain to embrace the enormous territories of the Spanish, including much of the Americas. Britain and the Netherlands (the British king, William III, was the Prince of Orange from Holland), along with other European powers, could not tolerate a combined French-Spanish empire as that would upset the balance of power in Europe.

Exhaustion

So war broke out–in multiple places across the continent and beyond, including in North, Central and South America. Finally physical and financial exhaustion brought all parties to the table after more than a decade of bloody war costing the lives of a million soldiers.

The peace negotiated in the Utrecht town hall marked the end of Holland’s Golden Age as the leading naval and trading nation and the beginning of Britain’s glorious era of ruling the waves.

Spain too was a spent force, surrendering Gibraltar to the British; while the French lost their grip on Canada which now became fully British, with a negotiated concession for the French language still to be used in Quebec.

The peace was celebrated on all sides, but especially by the British. Hence Handel’s commission.

So why am I telling you all this?

On Saturday Romkje and I joined a guided tour around Utrecht to learn about the Peace of Utrecht. We also learned that these wars opening the 18th century followed directly on from the 17th century in which there were only four years of peace in Europe.

By the time Handel wrote his celebrated Messiah, in 1742, aged 57, the Austrian War of Succession had broken out, ending the Peace of Utrecht.

War has been the default setting in Europe through the centuries. The period of peace and freedom we have enjoyed since World War II is truly exceptional.

Today war among these former combatants is unthinkable. Yet in 1950, it was unthinkable that war in Europe could become unthinkable.

Revelation

But when we take peace and freedom for granted, we risk losing both.

This is why we find it important to pause to reflect on Europe Day, May 9, about the vision and the values on which we can maintain peace and freedom in Europe. Robert Schuman’s understanding that the source of the soul of Europe, the life breathed into the culture and society of the European peoples, was the revelation of Jesus Christ, is still hugely relevant in these secular times.

Handel’s Utrecht Te Deum expressed this recognition. It is based on two liturgical texts of worship: the Te Deum, or ‘We praise thee, O God’, attributed to Ambrose, bishop of Milan, on the occasion of the baptism of Augustine; and Psalm 100, O be joyful in the Lord, all ye lands, from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.

Next week on Europe Day in Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral–whose choir sang the world’s first performance of the Messiah in a hall a stone’s throw away–we will open the State of Europe Forum* with worship and prayer. Accompanied by the cathedral organ, we will ask the Prince of Peace to be our vision, our wisdom and our breastplate as we face uncertain times ahead. And we will thank God for the peace we continue to enjoy in this era we mercifully can still call ‘post-war’.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,