Beyond the sentimental glitz, music and food, Christmas can be very unsettling.

Now for the fourth time since Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, we are celebrating the Word of God becoming flesh as angels proclaimed peace on earth. So where is the peace?

The idea of ‘immensity-confined’ in a human infant is itself mind-boggling and strains rationality. But the two-thousand-year promise of peace on earth in the midst of the Kremlin’s daily barbaric attacks seems an outright contradiction. As does the distinct lack of peace and goodwill in the very region where the angels sang their proclamation. Frankly the sweet Christmas carols seem totally detached from today’s headlines.

So how do we reconcile this tension?

If the goal of the incarnation had been the immediate eradication of conflict, then yes, it was a failure. Jesus was born in occupied territory, grew up in occupied territory, and was killed by soldiers of the occupying army. Not really something to celebrate.

Moreover, Jesus himself seemed to contradict the angels: “Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34).

Paradox

Yet this paradox does not cancel the angelic promise. It clarifies it. The shalom the angels proclaimed was not merely the absence of war but the restoration of right relationship—between God and humanity, within human communities, and ultimately within creation itself. This peace is deeper than political stability, though it has political implications.

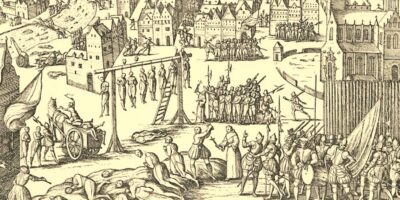

The peace Christ brings first exposes and disrupts false peace-systems of domination and injustice. Think of Pax Romana (and Palestine), Pax Britannica (and colonialism), Pax Americana (and Venezuela), Russky mir (and Ukraine).

In a world ordered by violence and power, true peace inevitably provokes resistance. Sometimes that resistance is cloaked in religious garb – as in Washington and Moscow today. Yet God’s Kingdom continues to spread – often from the fringes. Over time, even Rome embraced the babe of Bethlehem. Kings arose across Europe bearing crosses on their crowns.

We celebrate Christmas as the beginning of Jesus’ mission to inaugurate God’s reign, his order of flourishing life. His life embodied peace—healing, forgiveness and reconciliation. The kingdom had truly begun in Christ (‘already’). The incarnation inaugurated shalom but did not impose it instantaneously. In his death and resurrection, shalom is vindicated as the true future of the world. Yet the final reconciliation of all things awaits God’s consummating act (‘not yet’).

So two thousand years of conflict do not mean the promise failed. They are the long, contested middle ground of history between promise and fulfilment. Paul describes creation as ‘groaning’ in anticipation of liberation (Romans 8:22) – not the groan of defeat but the labour pain of a world being remade.

For many the incarnation may look like failure in a crucified Messiah. Yet the cross is not the negation of God’s purposes but their strange fulfilment. What appears weak is the deepest form of power.

So the goal of the incarnation was to reveal God’s character, reconcile humanity to God, and set history on a new trajectory toward restored creation. Its success cannot be measured by short-term political outcomes.

Scandal

God does not impose peace through overwhelming force; he invites, persuades, suffers… and waits. He does not override human freedom. He transforms it from within. No, the incarnation is not a great failure. It is the beginning of a peace that the world has not yet finished resisting. It is a decisive affirmation of the goodness, dignity and enduring purpose of the material world. God commits himself to creation’s future–contradicting both ancient and modern tendencies to spiritualise salvation and disparage physical reality.

In Genesis, God creates a physical cosmos and repeatedly pronounces it ‘good’. He formed humanity itself from the dust of the earth, animated his creation by his breath, and fused the material and the spiritual. By taking on human flesh, God affirms that materiality is not a problem to be escaped but a gift to be healed and fulfilled.

The scandal of the incarnation lies precisely here. In Jesus Christ, God does not merely appear human or temporarily inhabit a body as a disguise. He is conceived, born, grows, eats, weeps, suffers, and dies – in a particular place, culture and history.

God’s purposes are worked out not despite the physical world, but through it. Jesus heals bodies as well as souls. His miracles are signs that God’s reign involves the renewal of physical life. The resurrection is not the abandonment of the body but its transformation. The risen Christ bears wounds, eats food, and remains recognisably human, indicating that embodiment belongs to God’s future.

The incarnation therefore points forward, not just backward. If God honours the physical world by dwelling within it, then care for bodies, communities, cultures and our environment becomes a theological responsibility, not a secondary concern.

The Word made flesh assures us that creation is not disposable. History is not meaningless. The future of this earth lies in resurrection and renewal. Not in annihilation.

And that’s something to celebrate!

Till next week,

[…] I receive Jeff Fountain’s weekly newsletter. His latest is Why Celebrate. […]