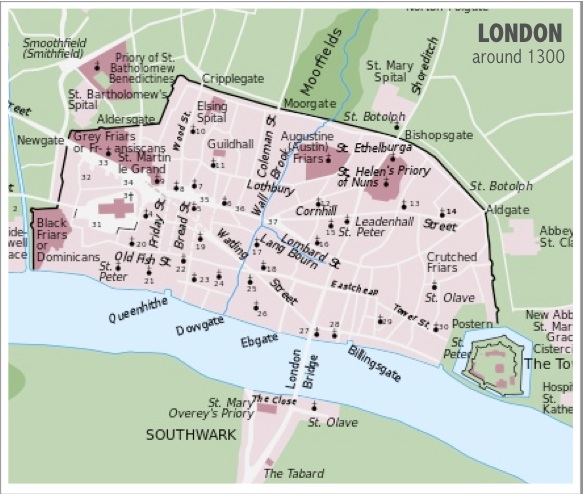

London, like virtually every other European city older than 500 years, was for a large part made up of churches and monasteries. Hence Erasmus could ask at the time of the Reformation, what is a city if not one big monastery? As early as 1300 London boasted over thirty churches and a dozen monasteries crammed within the city walls.

London, like virtually every other European city older than 500 years, was for a large part made up of churches and monasteries. Hence Erasmus could ask at the time of the Reformation, what is a city if not one big monastery? As early as 1300 London boasted over thirty churches and a dozen monasteries crammed within the city walls.

How tempting it would become for Henry VIII to simply disestablish the sprawling monasteries and convents and grab their lands and possessions. Not being one to resist temptation, he did precisely that–after settling his own divorce, marrying his mistress and replacing the pope with himself as head of the Church of England.

Names of the monasteries have survived where buildings have not: Blackfriars (Dominicans), Greyfriars (Franciscans), St Bartholomew’s (Benedictines), Austin Friars (Augustines), Crutched Friars, St Helen’s Priory of Nuns, Abbey of St Clare, and St Mary Overey’s Priory in Southwark, to name a few.

On our last day of the Celtic Heritage Tour last month, our party of 14 pilgrims traced Henry’s bloody trail to the Tower of London, where nearby the execution site of over 125 condemned men and women is marked by a bronze plaque revealing the names of those who fell foul of the king. It reads like the cast of characters in a Hilary Mantel novel: Thomas Cromwell, Sir Thomas Wyatt (rumoured to have been the queen’s lover), Thomas Howard (it was dangerous to be named Thomas)…

Cheerful

Nearby is a pub with the intriguing name in large letters: ‘The Hung, Drawn and Quartered’, under which a plaque reads: ‘I went to see Major General Harrison hung, drawn and quartered. He was looking as cheerful as any man could in that condition’. Samuel Pepys, 13th October 1660. Human rights apparently were not high on the priority list inTudor England.

Earlier we had started our visit at Westminster–yet another monastery–where we saw evidence of more humanitarian eras in London’s history. As we stood on the site of William Wilberforces’ house opposite Parliament, our guide briefed us on Oliver Cromwell’s role (great-great-grandson of Thomas' sister) in establishing parliamentary democracy. After learning about Cromwell’s ruthless and bloody policies in Ireland over the previous ten days, it was good to hear he had at least done something good.

We made brief acquaintance with women’s suffragette leader Emily Pankhurst, or at least her bronze image, in the park, and a neo-gothic memorial for Sir Thomas Buxton, successor to Wilberforce in the fight against slavery. While Wilberforce saw the end of the slave trade in 1807, Buxton fought on until every slave in the British Empire was freed in 1833.

Heroes

Next we stopped along the Thames Embankment, opposite the London Eye, where statues remind passers-by of more English heroes. Our interest was in Samuel Plimsoll and William Tyndale. Plimsoll fought a long battle to save the lives of thousands of sailors and passengers by instituting safety laws for ships. Tyndale, martyred near Brussels, pioneered the English Bible. Further down the Thames we stopped off at the dock where his New Testaments were smuggled ashore from the continent.

Just north of the old city walls, we discovered the Bunhill Fields Burial Ground, where such non-conformists were laid to rest as John Bunyan, William Blake, Daniel Defoe and Susanna Wesley. Her son John lies buried across the road on the site of the mother Methodist church. Around the corner one can still see George Whitefield’s Tabernacle.

Just enough time was left to head towards Whitechapel (there’s surely a story in that name) in East London where a statue of William Booth preaching near the Blind Beggar Tavern witnesses to the birth of the Salvation Army.

One day can only begin to offer a glimpse of the spiritual wealth this city has offered to our world.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,