An early church father’s exhortation to seek the common good comes as a refreshing reminder of our task as Christians today in a Europe unsettled by resurgent nationalism, populism and xenophobia.

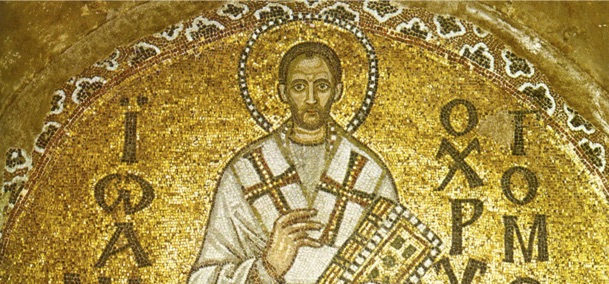

John Chrysostom–literally ‘the golden-mouthed’, in reference to his eloquent preaching–was the Archbishop of Constantinople at the beginning of the fifth century. Widely popular, he challenged the wealthy and the clergy through his preaching against the the abuses of riches and authority. ‘Do you wish to honour the body of Christ?’ he preached. ‘Do not ignore him when he is naked. Do not pay him homage in the temple clad in silk, only then to neglect him outside where he is cold and ill-clad.’

His down-to-earth preaching and practical Christianity attracted many to the faith in his day. ‘What good is it if the Eucharistic table is overloaded with golden chalices when your brother is dying of hunger?’ he asked. ‘Start by satisfying his hunger and then with what is left you may adorn the altar as well.’

Practising what he preached, Chrysostom established a network of hospitals in Constantinople, a precedent followed by many other church leaders through the centuries. His mosaic portrait (above) can still be seen in the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul today, built 130 years after his death and the world’s biggest cathedral until the Ottoman conquest.

Common good

As apt as the above quotes are in our world of increasing inequality, what is particularly relevant for our times is the following:

‘The most perfect Christianity is the seeking of the common good… for nothing can so make a person an imitator of Christ as caring for his neighbours.’

For Jesus taught that the law and the prophets were summed up in the commandment to love God and love your neighbour.

‘The common good’ was not Chrysostom’s original phrase. Plato and Aristotle had used the term centuries before. The 2nd century Epistle of Barnabas had also exhorted readers: ‘Do not live entirely isolated, having retreated into yourselves, as if you were already [fully] justified, but gather instead to seek together the common good’. And Augustine’s The City of God gave an affirmative answer to the question, ‘Is human well-being found in the good of the whole society, the common good?’

Many secular philosophers–from Machiavelli to John Stuart Mills–have also used the phrase, albeit mainly in an economic sense.

Ultimate goal

Yet the American socio-political activist and writer Jim Wallis believes this basic biblical imperative must be recovered by God’s people everywhere today in response to the current ‘them-and-us’/‘culture wars’ mentality too prevalent among believers.

In his book, in The (Un)Common Good, he writes that ‘we ought to be good neighbours to those around us regardless of whether we share their ethnicity, religion, gender, background, education or social status.’

Looking back on the development of church renewal over the past fifty years, as we did last week in this blog, Wallis believes the time is ripe for a new phase of renewal, expressing God’s ultimate goal for human history: shalom, right-relatedness, righteousness and justice.

God’s purposes involve the reconciliation of all things under heaven and on earth, including all peoples, tribes, nations and tongues. God’s future is multi-cultural and multi-national. God’s people now therefore need to be bridge-builders, not wall-builders; inclusive not exclusive; seekers of the welfare of the other, not ‘me first’, ‘my country first’.

Those of us with protestant, evangelical or pentecostal backgrounds need to recognise that each of these movements emerged as separatist minorities in an often hostile environment, with a clear ‘them and us’ demarcation. Hence we learned to stress our differences. It is still deep in our DNA.

Yet a longer Christian tradition teaches us that in addition to belonging to God’s family of grace, we are members of God’s human family. Each human being bears his image and thus has dignity. Hence Jesus’ shocking story about the Good Samaritan in which the hero belonged to ‘them’, not ‘us’.

Gathered in Geneva with fellow YWAM leaders two weeks ago, we reflected on John Calvin’s definition of the God-given task of political leaders as ‘to work for the common good’. This could be applied to spiritual leaders as well: to seek the common good of the congregation, of the body of Christ across the town or city, of the welfare (common good) of the city itself, and of the whole nation. And even beyond.

For this concept of the common good, rooted in Jesus’ teaching, was the conscious motivation of the Frenchman Robert Schuman to propose after the war that Europe would be a better place if its peoples and nations would work together. Then Europe could also serve other parts of the world, particularly Africa.

Imagine how better the world would be if God’s family of grace would truly follow Chrysostom’s advice.

Till next week,