Although Europeans and Americans have much in common, often they have seen things differently. One area where Americans got it right was the separation of church and state in their constitution.

Many on this side of the pond have understood that church-state separation meant that the proper place for religion was in the closet, not in the public square. Believe what you like, fine, but don’t bring your religion into politics. Dominant voices have argued that religion’s role in history has only been destructive–witness the Crusades, the Inquisition, the Religious Wars, the Irish problem, and now, behold: President Trump, voted in by hordes of Evangelicals!

The church-state divide, seen as an Enlightenment innovation, should have resulted in freedom from religion, these voices would argue.

For many American settlers, however, the separation of church and state meant freedom for religion. As religious refugees, they looked for freedom from oppressive regimes, secular and ecclesiastical–Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran and Reformed–back on the continent: e.g. the Pilgrim Fathers in Massachusetts, Mennonites in Pennsylvania and Catholics in Maryland. Irish migrants were escaping intolerable conditions under British political rule with religious overtones. No one denomination or religion should be favoured, they argued. All churches and religions should have an equal playing field.

The practice of church-state separation in Europe is by no means uniform, as sometimes is believed. A huge variety exists, from Ireland whose constitution begins: ‘In the Name of the Most Holy Trinity…’, through to France where the concept of laïcité keeps religion out of politics.

However it is this French attitude that has often been dominant in EU circles. During the drafting of the proposed constitution in 2003, Europe’s debt to ancient Greece and Rome was happily acknowledged, along with the achievements of the Enlightenment. Nothing however was said about the Christian roots of European civilisation.

Too little

As well-known secular British columnist and author, Tom Holland, has written, that would have been news to men such as Konrad Adenauer and Robert Schuman. They had consciously set out to rebuild Europe on Christian foundations. Schuman’s vision for Europe was for a ‘community of peoples deeply rooted in Christian values’. He believed democracy had to be Christian or it would become anarchy or totalitarianism.

Holland writes that the Bible was not merely a tool of the mighty. It served as well to endow the weak, the poor and the needy with a value that they never before possessed. No text has done more to underpin the construction of a new and multicultural identity for the continent than the Sermon on the Mount, he writes; it is not enough for Europeans merely to tolerate different cultures: they must learn to respect and embrace them as well. Then he quotes Angela Merkel: “We don’t have too much Islam; we have too little Christianity”.

That is certainly true given recent events which seem to represent the end of the era starting around 1949, my birth year–when NATO was formed, the UN was set up, and the first steps towards the EU were taken. The fruit of isolationism, protectionism, ethnic nationalism and disdain for collective security will need to be judged in the light of the biblically-derived values of human dignity, solidarity, common good and moral equality.

The source

In times like these we need to go back to the source–‘ad fontes’–as Erasmus pleaded five centuries ago when Europe was also facing multiple crises. The ‘source’ he had in mind was the teaching of the gospels, the epistles and the early church fathers–not in the first place the classical philosophers of Greece and Rome, as humanists today try to make him say.

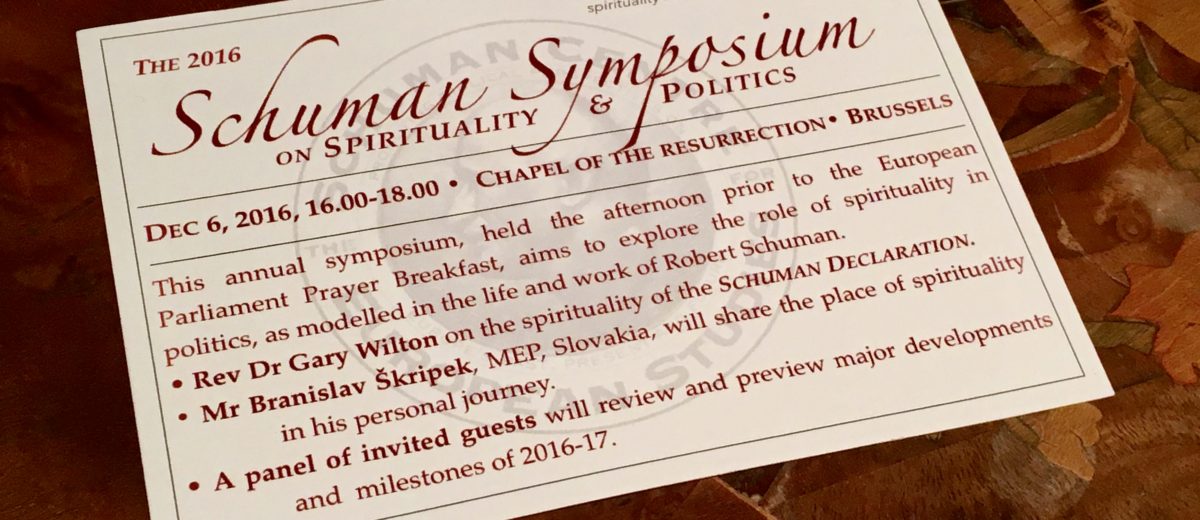

We need to draw on spiritual resources to guide us in these times of political uncertainty. With this in mind, we invite any concerned about Europe’s future to the second Schuman Symposium on Spirituality and Politics in Brussels two weeks tomorrow, on Tuesday, December 6.

Gary Wilton, co-editor of ‘God and the EU’ and former representative of the Archbishop of Canterbury to the EU, will talk about the spirituality of the Schuman Declaration, the three-minute proposal made on May 9, 1950, seen as the birth certificate of the European project.

Slovakian MEP, Branislav Škripek, a strong believer in the power of prayer in the public square, will share about his own spiritual pilgrimage into European politics.

They will be joined by other guests in a panel reflecting on developments of the past bumpy year–including the refugee crisis, Brexit and the Trump election–and what these could mean for us all in the coming year.

Come and join us in the Chapel of the Resurrection at 16.00. We’ll need all the foresight we can get as we prepare for 2017!

Till next week,