The widespread condemnation of the recent forced landing of the Ryanair flight over Belarus led me to ponder the influence of a Dutchman considered to be the father of modern international law: Hugo Grotius.

Just 250 metres from our apartment, his statue stands by the former Amsterdam exchange building looking out towards the harbour. Grotius, or de Groot, holds a thick volume entitled Mare Liberum (The Free Sea). The sea was international territory and all nations were free to use it for seafaring trade, argues the book.

I walked past this statue a few days ago with my 10-year-old grandson and asked him what he knew about Grotius. Like most Dutch schoolkids, he could immediately answer: that he escaped from imprisonment in a castle in a book chest.

This story is part of the offical canon of Dutch history. Grotius (1583-1645) lived his whole life during the Eighty Years War between the Netherlands and Spain (1578-1648). During a Twelve Year Truce (1609-1621), the Dutch stopped fighting the Spanish long enough to begin fighting among themselves – over theology. Grotius was advisor to a leading statesman in the fight against Spain, Johan van Oldenbarneveldt. Prince Maurits of Orange blamed these two for destabilising the political climate and had them arrested and tried in 1619. Van Oldenbarneveldt was sentenced to death, Grotius to life imprisonment in Loevestein Castle near the town of Gorinchem.

Escape

In 1621, Grotius’ wife Maria devised a plan for him escape in a large chest carried into the castle to deliver books for him to study. He climbed into the chest which was duly carried out across the drawbridge.

Once free, Grotius fled to Paris. There he published his most famous book, De jure belli ac pacis (On the Law of War and Peace) which laid down a system of principles of natural law that bound all nations regardless of local custom or law. He spent the rest of his life in exile abroad. His last decade – as the Swedish ambassador to France – was spent negotiating the end of the Thirty Years War.

So what does this have to do with the Ryanair ‘hijacking’ incident?

The outcry that followed this event demonstrates that nations, governments and populations everywhere expect justice and fair play, and for international agreements to be upheld. But if we teach that humans are simply freak products of a long materialistic process, why not let the law of the jungle – the survival of the fittest – prevail? Obviously no civilisation can be built on such a premise, let alone any international order.

The fact is, international law has been hugely shaped by the premise that there is a God to whom all human life is accountable. Something Dutch schoolkids don’t learn about Grotius is that his Christian faith and worldview shaped his thinking about how nations should relate to each other. Theology still plays a key background role in international politics because what we believe about God shapes our beliefs about humans and society. Which is what politics is all about.

International law had a name even back in Roman times: ius gentium, the law of the nations, derived from the concept of natural law, or principles informed by conscience. Yet since the christianisation of the Roman Empire, the development of international law is a story shaped up until modern times by theological concepts argued by Christian thinkers including Irenaeus, Augustine, Aquinas, Luther and Calvin.

As European powers discovered new territories, theological debates arose about how to behave towards the newly encountered peoples. Did the command to ‘love your neighbour’ apply to them too?

Cornerstone

But it was Grotius more than any other person who established international law as a distinct field, defining relations between nations in times of both war and peace. Mare Liberum, upholding the freedom of the high seas, was not only relevant to the growing number of European states exploring and colonising the world, but remains a cornerstone of international law today.

Grotius died three years before the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 ended both the Eighty Years War and the Thirty Years War. Yet his work shaped the framework of this watershed event, ushering in the current international legal order based on independent sovereign entities known as ‘nation states’. Regardless of size and power, states have equality of sovereignty defined primarily by the inviolability of borders and non-interference in their domestic affairs.

Today sovereignty has been qualified in a globalised world where countless international agreements bind nations together in mutual accountability, yet still based on Grotius’ legal order.

While Darwinians might applaud Lukashenko’s ‘strong-man’ tactics, Grotius points to a higher authority to whom the dictator is ultimately accountable.

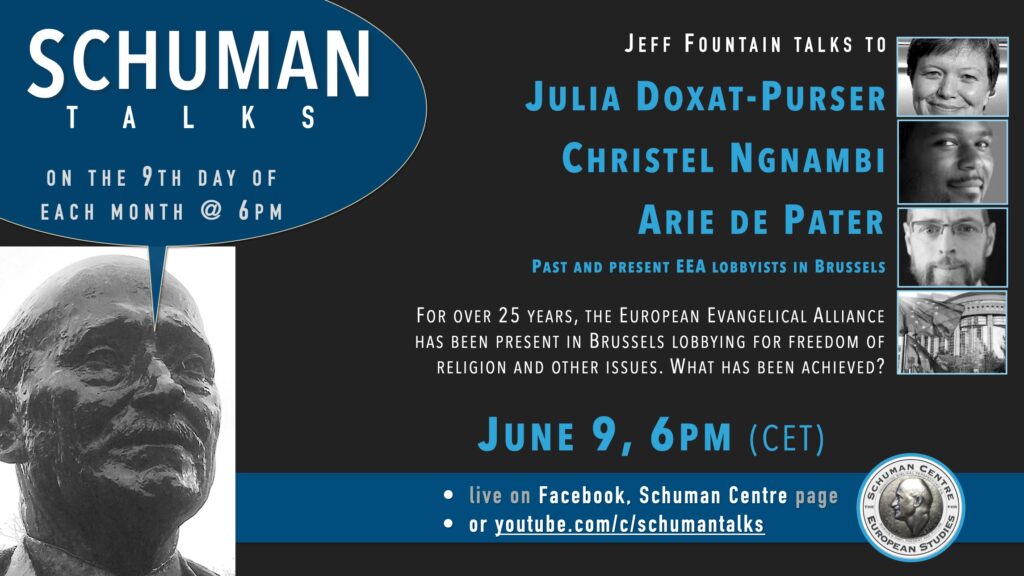

Join us on Wednesday at 18.00 CEST as I talk with three personal friends who are or have been working at the interface between politics and theology in Brussels: Julia Doxat-Purser, Christel Ngnambi and Arie de Pater, of the European Evangelical Alliance socio-political staff.

Go to: YouTube.com/c/schumantalks

Till next week,