Driving home through eastern France from Switzerland last month, my wife and I just happened to travel through a town I had visited once or twice before. On hearing the name, Romkje suspected a set-up, being used to my diversions to ‘check out some significant historical site’.

But in truth, we had chanced upon Luxeuil-les-Bains, one of the numerous locations where the larger-than-life figure of Columbanus had pioneered monastic communities of several thousand youth in his efforts to re-evangelise the half-converted Franks and reach the pagan Suevi of the sixth and seventh centuries.

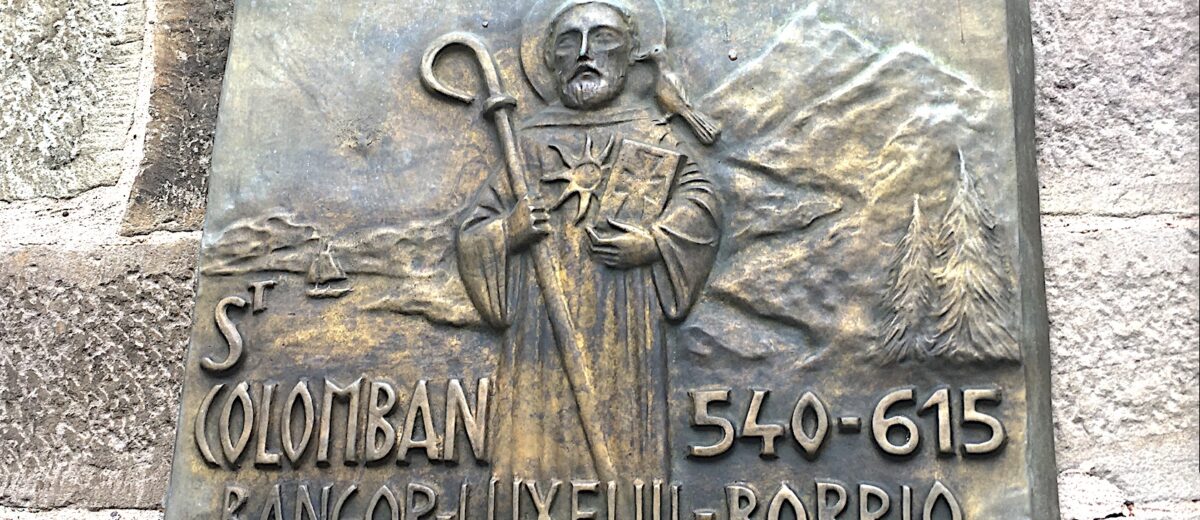

Numerous statues and plaques in the centre of Luxeuil testified that the memory of this Irish monk among the French (at least the inhabitants of this town) had not dimmed over 1400 years. One dramatic pose captured Columbanus with one arm stretched forward with his staff, the other drawn backwards over his head as if about to deliver a strong prophetic outburst. His hair was shorn in Celtic style, everything forward of a line drawn over his head from ear to ear, the sign of slavery adopted by the Celtic monks signifying total allegiance to Jesus as lord.

A few hundred metres away, in front of the abbey still named after its founder, stood another large bronze sculpture of Columbanus. A long flourishing inscription described the town’s ‘fondateur et patron’ as ‘an apostle with a soul of fire and an indefatigable walker to the stars whose radiant sun shone throughout the high Middle Ages’. A further paragraph of lavish poetic praise climaxed with a sentence in large upper case letters: LE SAUVEUR DE LA CIVILISATION.

Enemies and exile

Saviour? of civilisation?! Really?! Was this just Gallic hyperbole? Not at least for the French inhabitants of Luxeuil-les-Bains, nor for many Irish today. For them Columbanus is a colossus of history who led a movement of intrepid wandering preachers deep into the heart of Europe, becoming known as ‘disciplers of nations and teachers of kings’ as they transformed European history.

After 25 years of living as a monk in Bangor, near today’s Belfast, the 50-year-old Columbanus set sail around 590 with twelve companions for Gaul. The Christianisation of the Franks, begun almost a century earlier, had stagnated in aristocratic and political circles. The Irish newcomers brought fresh apostolic and evangelistic dynamism and quickly planted monastic communities in Annegray, Fontaines and among the ruins of Luxeuil, a Roman town ravaged by Attila the Hun in 451. Soon Luxeuil was the most important and flourishing monastery in Gaul, with perpetual prayers and worship being offered day and night.

Columbanus’ apostolic and uncompromising zeal also won him enemies in high places – and, after two decades, exile from Luxeuil. Undeterred, the feisty evangelist grasped the opportunity to pioneer in regions beyond. Well past retirement age, he struck out towards the Alps. Younger and less fit brothers, unable to match his pace, settled en route to start their own communities, becoming in time historic monasteries such as Lure in France and St Gallen in Switzerland. Crossing into Lombardy in northern Italy, the septuagenarian monk built his last monastery in Bobbio, where he died in 615. Still operating today, Bobbio is where Saint Francis would later develop his love for God’s creation.

Scriptoria and libraries

Columbanus was the first Irishman to have left behind a body of written work and to be the subject of a biography. His legacy not only included his own letters, poems and sermons revealing Irish humour and the influence of classical writers. He also fathered a network of over sixty (some say a hundred) monasteries with scriptoria and libraries in France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Austria and the Czech Republic. There classic Latin writings, lost to the rest of Europe through barbarian invasions and the collapse of Rome, were copied from manuscripts preserved in ‘the land of saints and scholars’, and improved with illustrations, punctuation, word separation and miniscule or lower case letters. These priceless hand-bound volumes were then hand-carried over mountains and valleys across the European mainland to reintroduce classical learning and the works of the early church fathers. Wherever they went, wrote American-Irish professor Thomas Cahill, ‘the Irish brought with them their books, many unseen in Europe for centuries and tied to their waists… just as Irish heroes had once tied to their waists their enemies’ heads. And that is how the Irish saved civilisation’.

Columbanus is said to have had a greater influence in France and Europe than any other Irish person, living or dead. Former Irish president Mary McAleese went a step further when in 2015, on the 1400th anniversary of the monk’s death, she narrated a film for Irish television under the title, ‘The man who saved Europe’. In the (highly recommended) film, available online re-titled as The monk who united Europe, McAleese quotes Robert Schuman describing Columbanus as a ‘patron saint of all those who today seek to build a united Europe’. ‘His ideas saved Europe then’, says McAleese introducing the film, ‘and they are needed again today’.

Till next week,

No wonder St. Francis had such a love for creation if he was influenced by the Celtic monks who themselves were so in tune with the creation around them and loved it. Wish that was clearer for Christians today who think that care for Creation is not their job.

I finally read this wonderful letter. It brings hope of how even a few people who are sold out for kingdom purposes can influence an entire society. Thank you Jeff for seeing out these historical treasures of Christian influence in Europe.