Despite initially strong opposition to his visit to the European Parliament, Pope Francis received repeated rounds of applause on his visit to Strasbourg last week even as he urged his listeners to ‘return to the firm conviction of the founders of the European Union’, a vision revolving around the sacredness of the human person, not the economy.

Despite initially strong opposition to his visit to the European Parliament, Pope Francis received repeated rounds of applause on his visit to Strasbourg last week even as he urged his listeners to ‘return to the firm conviction of the founders of the European Union’, a vision revolving around the sacredness of the human person, not the economy.

Quoting an anonymous second-century author, the pontiff said: “Christians are to the world what the soul is to the body”, bold words not usually heard in that auditorium. The function of the soul, he continued, was to support the body, to be its conscience and its historical memory.

The invitation from the President of the EP, Martin Schultz, after an audience with the pontiff in Rome last year, was noteworthy in the light of the German socialist’s opposition in 2004 to an Italian nominee to the EU’s Commission due to his personal stance supporting Catholic teachings on abortion and homosexuality.

This did not prevent Francis from delivering to the members of the EP an unambiguous challenge to return to the values which had nurtured European life and society over many centuries, and which had inspired the fathers of the EU in the post-war years.

“I would like, as a pastor, to offer a message of hope and encouragement to all the citizens of Europe,” he began. “It is a message of hope, based on the confidence that our problems can become powerful forces for unity in working to overcome all those fears which Europe–together with the entire world–is presently experiencing. It is a message of hope in the Lord, who turns evil into good and death into life. It is a message of encouragement to return to the firm conviction of the founders of the European Union.”

Transcendent Dignity

At the heart of this ambitious political project was confidence in man, he continued, not so much as a citizen or an economic agent, but in men and women as persons endowed with transcendent dignity.

The pope stressed the close bond between the words ‘dignity’ and ‘transcendent’. To speak of transcendent human dignity meant appealing to our innate capacity to distinguish good from evil, to that ‘compass’ deep within our hearts, which God had impressed upon all creation, he argued.

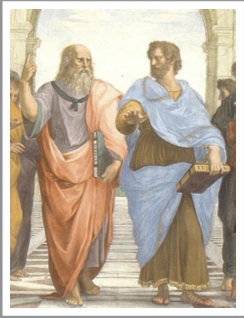

How could hope in the future be restored, he asked, for the great ideal of a united and peaceful Europe, a Europe respectful of rights and conscious of its duties? To answer his own question, Francis referred to the celebrated Raphael frescoe in the Vatican, the ‘School of Athens’, with Plato and Aristotle in the centre. Plato’s finger points upward, to the world of ideas, to the sky, to heaven; Aristotle holds his hand out before him, towards the viewer, towards the world, concrete reality.

“This strikes me as a very apt image of Europe and her history, made up of the constant interplay between heaven and earth, where the sky suggests that openness to the transcendent–to God–which has always distinguished the peoples of Europe, while the earth represents Europe’s practical and concrete ability to confront situations and problems.

“The future of Europe depends on the recovery of the vital connection between these two elements. A Europe no longer open to the transcendent dimension of life is a Europe which risks slowly losing its own soul and that ‘humanistic spirit’ which it still loves and defends.”

Enrichment

The centrality of the human person was part of the legacy that Christianity had offered to the social and cultural formation of the continent, Francis explained, and continued to offer today, and in the future, to Europe’s growth. Seeking to reassure his largely secular audience, he stressed this Christian contribution was not a threat to the secularity of states or to the independence of the EU institutions, but rather was an enrichment. “This is clear from the (Christian-inspired) ideals which shaped Europe from the beginning, such as peace, subsidiarity and reciprocal solidarity, and a humanism centred on respect for the dignity of the human person.”

A Europe capable of appreciating its religious roots would be all the more immune to the extremism spreading in the world today, he proposed. Citing his predecessor, Benedict XVI, he said: “It is precisely man’s forgetfulness of God, and his failure to give him glory, which gives rise to violence.”

The pope warned his listeners that by allowing technical and economic questions to dominate, Europe now displayed a haggard weariness and aging, like a ‘grandmother’, no longer fertile and vibrant. The great ideas which had once inspired Europe had lost their attraction. Bureaucratic technicalities, a ‘throwaway’ culture, mistrust, alienation and selfish, unsustainable lifestyles were the result.

A two-thousand-year-old history linked Europe and Christianity, he continued. That history had still to be written. “It is our present and our future. It is our identity.”

Till next week, [Read full speech here]

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,