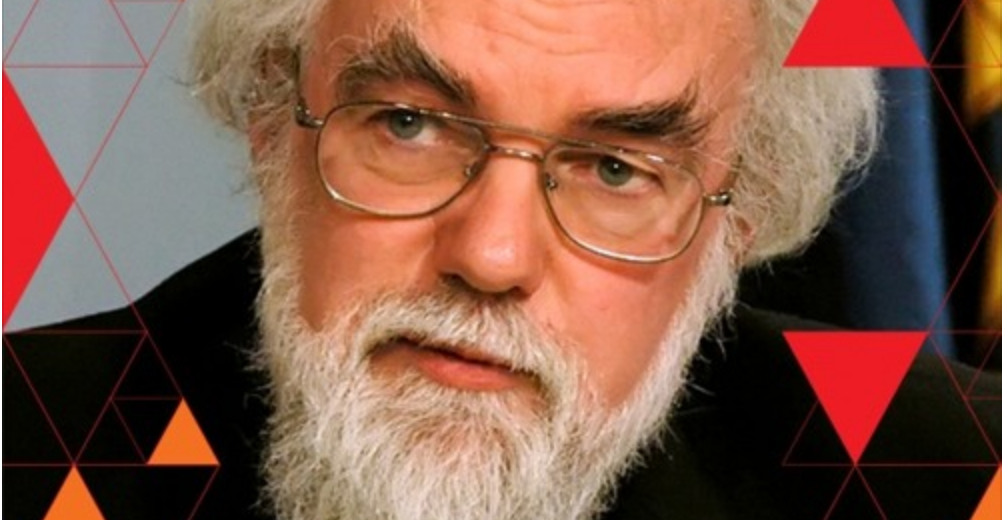

Rowan Williams, the former Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, speaking in The Netherlands on Monday warned about the failure of mass democracy, as the German election results signalled the return of neo-nazis to the Bundestag for the first time since World War Two.

“I don’t believe we are on the verge of a resurgent fascism,” I heard him tell his audience in a crowded lecture hall at Radboud University in Nijmegen, “but it’s important to recognise the point of crisis in our understanding of democracy.”

Against the backdrop of recent elections and referenda in America, Britain and continental Europe, he called for a far more developed and mature discussion about power and truth and the meaning of ‘democracy’. The alternative was to sink “into the deep swamp of mass democracy where opposition voices were denounced as ‘enemies of the people’”.

He began his lecture reminding his listeners that while today the word ‘democracy’ was used to denote something positive, in much of history it had been viewed negatively. Plato had seen it as the rule of the mob, power exercised by the crowd.

How then had it become the ultimate ideal of social justice and equity? The Enlightenment narrative had called for the replacement of a small group exercising unaccountable power – an autocracy, oligarchy or dictatorship – by a political authority enjoying a popular mandate. Instead of a top down, arbitrary and often religious authority, true legitimacy was seen to come from popular thought.

Tyranny

The last few decades, however, had shown that the removal of tyranny did not automatically produce democracy, he observed. When we took away transcendent political power, we were left with rational popular power. The popular mandate was presumed to be democracy.

However, said Williams, we needed to think again how we defined the word democracy. The rise of populism in Europe and the US was based on the claim that populism was a legitimate democratic expression of the ‘People’s will’. This was dangerously confused with the demographic ideal, warned the theologian, when democracy became the tyranny of the majority vote.

Quoting Plato, he asked why it was that justice was not to be identified with the interests of the stronger. The will of the majority should not determine the rights of minorities, he said, adding that the treatment of minorities was a sign of legitimacy of a democratic government. Political liberty required allowing dissent. Power did not establish the good.

The understanding of religious liberties was the beginning of the understanding of all political liberties, he said, citing Lord Acton. The majority’s right to determine law did not mean it could end all discussion. If justice was not the rule of the stronger, majorities did not determine what was right. The law did not end the argument. One might accept something as lawful but not necessarily right or true.

Legitimate democracy needed an opposition, Williams argued. Democracy failed when it closed opposition down, and smothered a civil society where different questions were raised. A moral democracy made room for argument and persuasion. In an argumentative democracy it was proper to go on arguing.

Diversity

A secular state needed a diversity of voices to keep the argument alive, he continued, especially non-secular voices. They should remind the state that to believe in the dignity and worth of the human being was itself an act of faith. Without that belief, the whole structure of democracy would collapse.

Democracy itself was a theological idea, suggested Williams, a view of community to be likened to the Body of Christ. When one part suffered, the whole suffered. Therefore every perspective was worth taking seriously.

Herein lay the failure of mass democracy: neither the power politics of elites nor the rise of populism could deliver security for a plural society. As a footnote, added the professor, the only good thing about the far right gaining seats in the German parliament was that there they would have to use persuasion and argument, which probably would mean a loss of credibility and reduced influence.

In question time, I asked Dr Williams to comment on the role of referenda in the failure of mass democracy. A referendum was a pretty blunt tool to be used very sparingly, he said. That it should have a decision-making influence, as with the Brexit referendum, was in his opinion most problematic.

• The European Christian Youth Parliament in Tallinn, Estonia, October 26-29, offers an opportunity for further exploration of the meaning of democracy today for young people from across Europe, and aims to equip them for effective persuasion in the public square through lectures from experts, peer discussions and personal mentoring. Check out the website.

Till next week,