The Pope, a rabbi and two atheists walked into a bar. The barkeeper said, ‘Is this some kind of a joke?’

The Pope, a rabbi and two atheists walked into a bar. The barkeeper said, ‘Is this some kind of a joke?’

Depends on your sense of humour, of course. A few weeks ago I picked up a book at the airport with the title, ‘Plato and a platypus walk into a bar: understanding philosophy through jokes.’

First, though, one has to understand the joke. Which, if one has a cross-cultural marriage, can’t always be taken for granted.

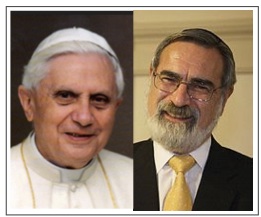

I do however have a specific pope and particular rabbi in mind who have given me a few chuckles recently in their dialogue with a couple of prominent atheists.

Last week, the Italian daily La Repubblica published excerpts from a letter Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI sent to mathematician Piergiorgio Odifreddi, the Richard Dawkins of Italy. The atheist had written a book in 2011 entitled: ‘Dear Pope, I’m writing to you’, critiquing some of Benedict’s arguments. In response, Benedict had written an 11-page letter to Odifreddi’s ‘surprise and excitement’, an answer which was ‘beyond reasonable hopes’.

Odifreddi said was particularly surprised that Benedict read his book from cover to cover and wanted to discuss it, as it had been billed as a ‘luciferian introduction to atheism.’ He plans to include the whole letter in the next edition of his book.

Science fiction

Benedict wrote: ‘My opinion about your book as a whole, however, is itself rather mixed. I read some parts with enjoyment and profit. In other parts, however, I was taken aback by the aggressiveness and rash nature of your argument.(…)

‘Several times you pointed out to me that theology must be science fiction….

‘Science fiction exists, moreover, in the context of many sciences. What it offers are theories about the beginning and the end of the world as found in Heisenberg, Schrödinger and others. I would designate such works as science fiction in the best sense: they are visions which anticipate true knowledge, although they are, in fact, only imaginative attempts to get closer to reality.’

And here comes the quiet humour of the pope:

‘There is, however, science fiction on a grand scale even within the theory of evolution. The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins is a classic example of science fiction.

‘The great [molecular biologist] Jacques Monod wrote some sentences which he has inserted in his works which could only be science fiction. I quote: "The emergence of tetrapod vertebrates… originates from the fact that a primitive fish ‘chose’ to go and explore the land, on which, however, it was unable to move except by jumping clumsily and thus creating, as a result of a modification of behaviour, the selective pressure leading to the development of the sturdy limbs of tetrapods. Among the descendants of this bold explorer, of this Magellan of evolution, some can run at a speed of 70 miles per hour…“‘

Benedict continues: ‘But I want especially to note that in your religion of mathematics three themes fundamental to human existence are not considered: freedom, love and evil. I'm astonished that you just give a nod to freedom, which has been and is the core value of modern times. Love, in this book, does not appear, and it says nothing about evil. Whatever neurobiology says or does not say about freedom, in the real drama of our history it is a present reality and must be taken into account. But your religion of mathematics doesn’t recognise any knowledge of evil. A religion that ignores these fundamental questions is empty.’

Superficial

Earlier this summer, The Spectator ran an article by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks opening with a remark made by one Oxford don about another, which had ‘more than once come to mind when reading the new atheists’, the author wrote, referring to Dawkins and co.: ‘On the surface, he’s profound, but deep down, he’s superficial.’ *

Chuckles aside, both the rabbi and the pope are deadly serious in pin-pointing the failure of secularism and atheism to grapple ‘with the real issues, which have… everything to do with the meaningfulness or otherwise of human life, the existence or non-existence of an objective moral order, the truth or falsity of the idea of human freedom…’

You cannot expect the foundations of western civilisation to crumble and leave the rest of the building intact, Sacks warns, adding that he has not yet found a secular ethic capable of sustaining in the long run a society of strong communities and families on the one hand, altruism, virtue, self-restraint, honour, obligation and trust on the other.

A century after a civilisation loses its soul it loses its freedom also, writes Sacks, who concludes: ‘That should concern all of us, believers and non-believers alike.’

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,