This week, while revisiting the Van Gogh Museum here in Amsterdam with friends, I was struck again by how much Vincent’s deep religious faith is ignored and misunderstood by the ‘experts’.

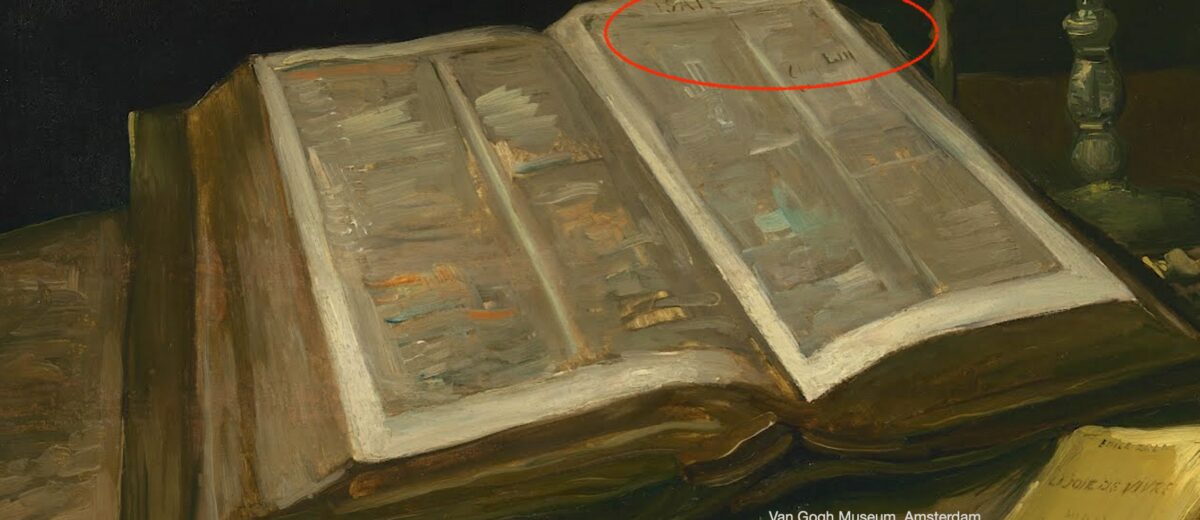

Take van Gogh’s Still life with Bible, shown here above. The text displayed next to the painting explains that the picture supposedly ‘symbolizes the difficult relationship van Gogh had with his father, setting the latter’s conservative attitudes against the modern view of life expressed in (Emile) Zola’s book (La Joie de Vivre): old against new, death against life, and the old-fashioned, dark leather binding of the Bible against the bright yellow book.’

This narrative is typical of many descriptions which divide the artist’s life into two halves, the first being fanatically religious, the other abandoning Christianity in favour of Natural Religion.

Another commentator wrote that for Vincent ‘the Bible represented everything he saw in his father: blind devotion to religion and faith, forever trapped in an antiquated mindset. In Zola’s book it can be argued that van Gogh was depicting the antithesis of his father’s Bible. A fresh and modern way of perceiving the world realistically, rather than the Bible which van Gogh felt caused “despair and indignation”. To van Gogh the Bible was looking backward while modern works by Zola and other writers he admired looked forward in inventive, new ways.’

Kathleen Powers Erickson challenges this perspective in her book, At Eternity’s Gate: the spiritual vision of Vincent van Gogh. She was astonished by reading van Gogh’s extensive correspondence to realise that his religious faith permeated his entire life and vision. His artistic work was in fact an extension of his earlier religious life and experience, she came to see, not an abrupt discontinuity. So she wrote her book ‘to show the continuity of van Gogh’s pilgrimage of faith, from his early religious training, through his evangelical period, to his struggle with religion and modernity, and finally to the synthesis of religion and modernity he achieved both in his life and his art.’

Rejection

Still life with Bible was painted just months after his father’s death in 1885, in the middle of that remarkable decade of Vincent’s artistic productivity which began in 1880 when he ceased his work as an evangelist to become an artist, and ended with his tragic death in 1890.

The year 1880 was indeed a pivotal year in Vincent’s life, when he rejected institutional Christianity and what he saw as the hypocrisy of the clergy. Yet he chose to centre his spiritual life on two of the most popular Christian devotionals, The imitation of Christ (Thomas a Kempis) and Pilgrim’s Progress (John Bunyan). ‘That book is sublime,’ he once wrote to his brother about the first book which he had personally copied out by hand. The choice to radically imitate Christ helps explain much of van Gogh’s life and struggle, and his embracing of sorrow and suffering as part of the pilgrimage ending in the Celestial City.

While art historians have consistently interpreted Still life with Bible as a rejection of van Gogh’s former Christian faith, Erickson asserts that it actually reflects his continued respect for the Scriptures. In the fall of 1888, Paul Gauguin wrote about van Gogh when he joined him in Arles that ‘his Dutch brain was afire with the Bible’.

Suffering

What is often missed is why Vincent chose to paint the Bible opened at a particular page of the prophet Isaiah. On the top right hand corner the French name Isaïe can be clearly seen. Why French? Was this really his father’s Bible? Would that not have shown the Dutch Jesaja?

Close to the top of the right hand column van Gogh has painted the chapter heading in Roman numerals: LIII. For in Isaiah 53, the prophet describes the servant of God as ‘despised and rejected by mankind, a man of suffering, acquainted with grief, …(who) bore our suffering, (was) pierced for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was on him, and by his wounds we are healed.‘

Vincent, like Christians throughout the centuries, interpreted this passage as portraying the suffering Christ. Characters in the novels of Zola and Hugo also suffered and sacrificed themselves to help others. Zola’s book was not the antithesis to the Bible, but complementary. Van Gogh consistently used the colour yellow to represent the divine presence – in the sun, moon and stars, sunflowers, fields of wheat – and the cover of Zola’s book.

In 1888, well into Vincent’s supposedly non-religious phase, he wrote to his friend Emile Bernard:

My dear Bernard, You do very well to read the Bible… The Bible — that’s Christ, because the Old Testament leads towards that summit; St Paul and the evangelists occupy the other slope of the holy mountain…. (Christ) lived serenely as an artist greater than all artists — disdaining marble and clay and paint — working in living flesh — this extraordinary artist… made neither statues nor paintings nor even books…he made living men immortals.

Still sounds like a believer to me.

Till next week,