Everyone’s heard of the American Dream, but who’s heard of the European Dream? Did we even know there was one? Ironically, it’s an American who writes about this–and who believes it is quietly eclipsing the American dream.

Everyone’s heard of the American Dream, but who’s heard of the European Dream? Did we even know there was one? Ironically, it’s an American who writes about this–and who believes it is quietly eclipsing the American dream.

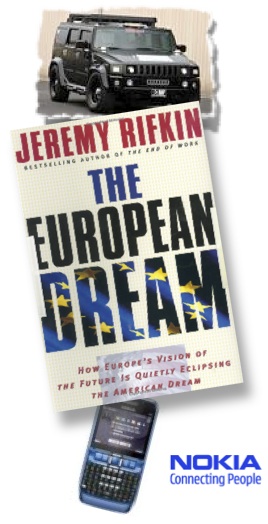

Jeremy Rifkin’s book, The European Dream, is now six years old and has been both praised and criticised on both sides of the Atlantic. The New York Times once stated that ‘many in the scholarly, religious, and political fields praise Jeremy Rifkin for a willingness to think big, raise controversial questions, and serve as a social and ethical prophet’.

Briefly, here’s what Rifkin argues.

The American Dream is fast approaching it’s use-by date. That dream has been built on both the Reformation and the Enlightenment, championing a concept of freedom rooted in autonomy and mobility.

To be free to go wherever and whenever, in the spirit of independence, enjoying the wide open spaces and the unlimited resources promised by the New World, was part of the dream shared by every immigrant arriving at Ellis Island, Rifkin argues. The icon of this dream was the automobile: that great enabler of autonomy and mobility.

But, he warns, this dream is not transferable to other parts of the world. It’s exclusive to North America. And it’s based on an outdated view of the world as a machine to be tinkered and toyed with.

Relationships

Across the pond, however, Rifkin has observed from his many sojourns in Europe the emergence of a different type of dream. This dream is based on a very different understanding of freedom, one embedded in relationships, on being connected with others.

It’s no coincidence that Europeans developed the mobile phone ahead of the Americans, he points out. The mobile phone has to be the icon of the European dream, he suggests, that great ‘connector of people’.

The European dream recognises, however, that the world’s resources are not unlimited, and is therefore committed to sustainability. The future will continue to include crowded cities and limited space, so freedom involves finding one’s place in the complex ecology in which we live. Stewardship rather than exploitation of our world belongs to this concept of freedom.

While property rights was an essential ingredient in the American dream, the European dream stresses human rights. Ownership is trumped by relationship in a world that is intrinsically interrelated.

This, claims Rifkin, is a transferable and inclusive dream, a model for other regions to follow, one which points the way forward.

Networks

Rifkin knows Europe from the inside. He has advised Germany’s Angela Merkel and Holland’s Jan Peter Balkenende, and written papers for Romano Prodi, the former president of the EU Commission. Prodi, he writes, was fond of talking about ‘Network Europe’ and saw the task of the EU as creating an environment for networks to develop across Europe’s national barriers.

I had to read this book by an American to learn about dozens of TEN’s–Trans-European Networks–in all spheres of European society: transport, energy, telecommunications, education (the Bologna, Comenius and da Vinci programmes), currency, banking, labour, air space, travel, sports, media, scientific research and high technology, among others.

But where is ‘Network Europe’ in the Body of Christ? Where is the awareness of our need to be connected as different churches, organisations and ministries across a city, a nation, a continent?

Why is it that ‘the world’ seems to be demonstrating ‘body-life’ better than we do in the Body of Christ?

Next week, I’ll share about a strategic event next spring, aimed to help leaders engage with today’s Europe through relational networks across the continent.

Till then,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,