Given the numbers of Jesus-followers supporting populist politicians on both sides of the Atlantic, it would be easy to assume that Jesus was a populist in his day.

In one sense, he was; if you take the dictionary definition of the word as meaning ‘support for the concerns of ordinary people’. Matthew (9:36) tells us that when Jesus saw the crowds, ‘he had compassion on them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd.’

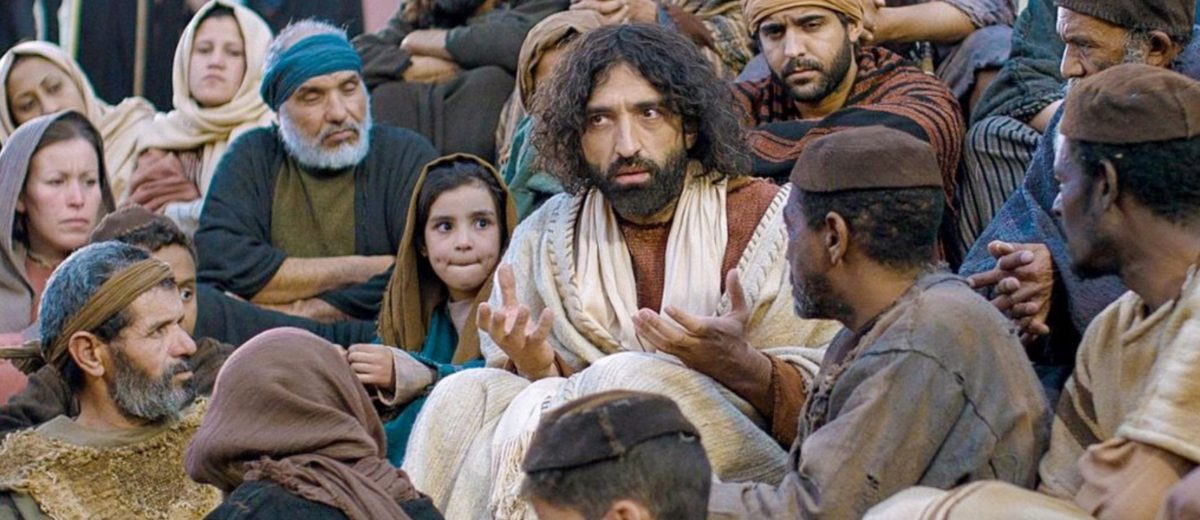

Crowds very quickly began to follow him as he started healing people and proclaiming that God’s kingdom was drawing near. Military occupation of Palestine by the Romans and the expectation that God would one day send a Messiah to liberate his people was part of his public appeal.

The elitist Pharisees felt threatened by his popularity and looked for faults to criticise: his disciples picking corn on the Sabbath or not washing hands before a meal; Jesus healing on the Sabbath or partying with prostitutes and tax collectors.

In his last week of ministry before the crucifixion, Jesus sharpened his criticism of the pharisees. While honouring their office, he spoke out seven woes over religious leaders who did not practise what they preached (Matt 23).

So, does this make Jesus a populist in the sense the term is used today, mobilising an alienated sector of the public against an out-of-touch self-serving elite? Did Jesus try to unite the ‘forgotten men’ against the corrupt dominant elites and experts? Was his plan to mobilise the masses into direct action? Did he make attractive promises to restore the good old days by getting rid of the Romans, the Samaritans or other Gentiles? Did he present ‘alternative facts’ to build or defend his popularity? Did he look for scapegoats to blame for contemporary problems? Was his message ‘Israel first’?

Provocative

Well, Jesus did tell his disciples to go to ‘Israel first’ on their first healing outreach, not to the Samaritans or the Gentiles (Matt 10:5,6). But this was a matter of priority, not principle. What became clear as Jesus’ ministry progressed was that he was a man for all peoples. His message was not of nationalism and hate but inclusion and love: ‘love your neighbour as yourself’; and even, ‘love your enemies’. By any standard, that’s pretty universal. Not much room for water-boarding in this command.

When asked ‘who is my neighbour?’, Jesus launched into the story of the Good Samaritan, a deliberately provocative allusion guaranteed to confront his listeners with their racial prejudice. In today’s context he may have talked of the Good Moroccan, the Good Mexican, the Good Turk, the Good Syrian… you name it.

Jesus rebuked both the disciples and the Jews for their unbelief by praising a Syro-Phoenician woman and a Roman centurion who had shown more faith than anything he had seen in Israel. Eventually he instructed his disciples to take the good news of his kingdom to peoples everywhere, a command that took the prejudiced early church years to comprehend.

Collusion

Jesus did not call for an overthrow of elites and experts. He didn’t preach, ‘let’s take back our country’. He did not find scapegoats either in the newcomers or the rulers. Rather he challenged each person to repent, to count the cost of following him, and to seek God’s kingdom in the first place. He became increasingly pointed in his criticism of the people who had not lived up to their calling as a whole, prophetically cursing the fruitless fig tree. He warned the Jews of the consequences of not using their talents for God’s purposes. He even told them the kingdom of God would be taken away from them and given to a people who would produce its fruit (Matt 21:43).

Populist demands ultimately led to his crucifixion by a collusion of elites, Jewish and Roman. Jesus sided with neither populist nor elite. At one stage he evaded the crowd trying to force him into becoming king.

When confronted with the dichotomy of ‘people’ or ‘elite’, Jesus refused to be cornered. His answers to trick questions introduced a new dimension. He rejected the narrow framework: ‘render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, to God the things that are God’s’.

Today we find often ourselves cornered by dichotomies, binary options: Clinton/Trump; Leave/remain; closed borders/open borders; our nation first/Europe…

It’s tempting to always want to have an answer. Sometimes Jesus just slipped away, or remained silent. Always he looked to see what the Father was doing, and responded in accordance with his character: of compassion, forgiveness, long-suffering, mercy, love, truth and justice.

Who then is our neighbour? who is our enemy? what does it mean to love them? and do they include the populists? the president? the prime minister?

What then does God require of me, but to do justly, love mercy and to walk humbly?

Till next week,