Three years ago this month, the Archbishop of Canterbury gathered a group of experts together at Lambeth Palace to seek ways to restore ethics and justice in global economics after the financial turmoil beginning in 2007.

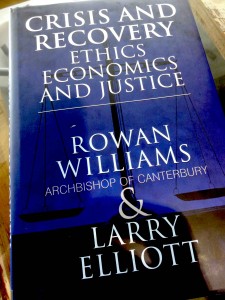

A year later, the discussion was published in book form with the title, Crisis and recovery: ethics, economics and justice. Rowan Williams, in his foreword, reveals the prevailing sense at the time that perhaps the worst was over, and that the temptation was thus ‘to drift towards the default setting of modern liberal capitalism once more’. The point of the book (which he co-edited with Larry Elliot, the economics editor of the Guardian) was ‘to insist that this would be monumentally irresponsible; as immoral as it is unintelligent’.

Strong words from the archbishop. But subsequent developments have shown such language to be fully justified. Two years further on, the crisis continues to deepen, is threatening the existence of the Euro, has brought Greece to the verge of bankruptcy and is putting immense strain on relationships within the EU.

The whole scenario is hugely complex and confusing for laypeople like myself. A handy volume of essays based on this consultation would be a welcome primer on the crisis, especially an evaluation in the light of biblical ethics. The pace of events has unfortunately quickly outdated some of the presentations, useful as they are for understanding the background and developments up to 2009.

The consultation was a British affair and understandably the book focuses on the British scene. However, as the archbishop represents a church with global reach, I had hoped for a broader perspective.

Ambitious plea

Nevertheless the Lambeth Palace initiative was laudable as a prophetic expression of the church. While Williams describes the book as ‘a modest collection of reflections on the disasters and follies of very recent times’, he adds his hope that it would be ‘an unashamedly immodest and ambitious plea for a renewal of political culture and social vision, a renewal of civic energy and creativity in our own country and worldwide’.

The nine chapters from economists, politicians, journalists and the archbishop himself address both economic issues and deeper questions concerning the kind of society we have become. After 30 years of rampant free market economics, we have seen governments having to step in with drastic Keynesian interventionist measures to rescue banks, financial institutions, personal savings and pensions, national economies, and now the Euro.

The nature and scale of this crisis is unprecedented, the book argues. The world’s financial system has gone through arguably the greatest crisis in the history of finance capitalism, wordwide in scale and personal in impact.

Elliot offers a very helpful overview of the development of the globalised economy following the collapse of communism, which allowed free movement of capital as digital technology created an unprecedented integrated market. The recent ‘near-death experience of the global economy‘ demanded a fundamental rethink, not just to prevent a future crisis, but also ‘to counter the threat of climate change, to divide the economic spoils more equitably, and to provide an alternative set of values’.

Wellbeing

Williams, who laments the sweeping aside of trust and personal relationships in the rush towards profit, anchors his observations in the parables of Jesus. More than once, Jesus used the world of economics as a framework–the parable of the talents, the dishonest steward, even the story of the lost coin. Economic relations reflect how we see our humanity.

Theology instructs all aspects of human life, especially a vision for shared wellbeing. An ethics-based economics promoted everyone’s wellbeing, as well as our fragile environment. Economics divorced from civic virtue, seen as ‘morally neutral’, undermines sustainable human society.

Other chapters in the book offer analyses of the crisis from a variety of perspectives and proposals for ethical and just economics. Zac Goldsmith’s contribution focuses on the alarming rate at which the ecosystems on which we depend are being damaged, a symptom of our dysfunctional relationship with the planet. Even without the current financial crisis, we face serious problems. Only at great peril do we ignore warnings from the Red Cross–that aid will not be able to keep pace with the impact of climate change–and from major financial institutions of economic disruption and social chaos for the same reason.

These issues are far too serious to be left only to economists and politicians. Archbishop Williams has initiated a vital debate that deserves to be picked up and sustained by disciples of Jesus in all walks of life, everywhere.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,

Great reading! Thanks.

One little correction to your piece: the interventions by the governments in the crisis have been anything but Keynesian. In fact, the problem at the moment is that not enough Keynesian anti-cyclical policies are being deployed. The austerity measures adopted by primarily European governments are creating a pro-cyclical (so enforcing the cycle) circle of problems. Cutting spending is reducing the economy, not stimulating it…