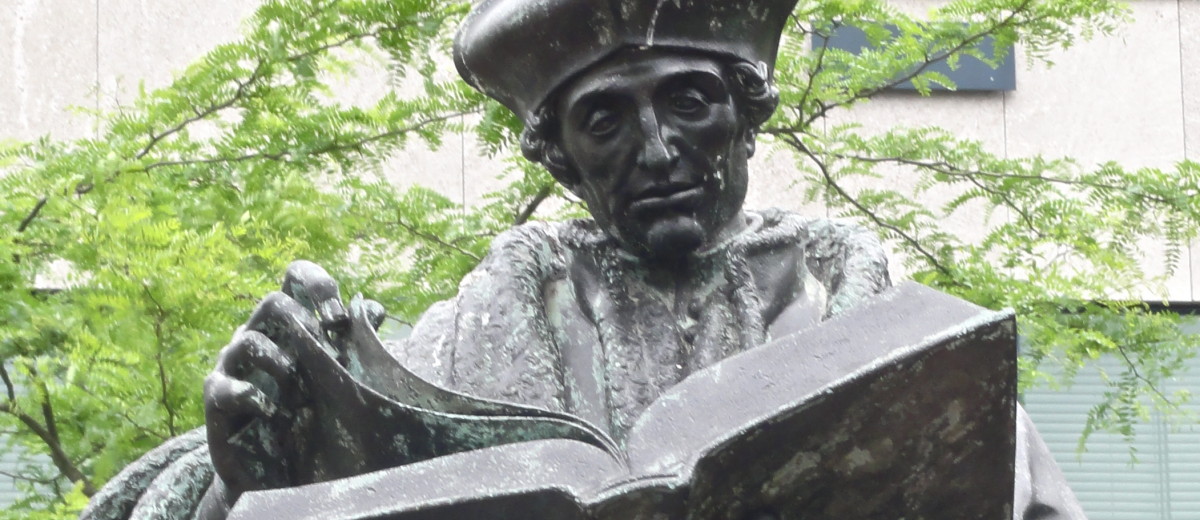

Five hundred years ago this week, a book destined to catalyse the reshaping of Europe came off the press in Basel. It was a bomb with a short fuse. The publication of this Greek-Latin New Testament was the crowning work of the great Renaissance scholar, Erasmus of Rotterdam.

For many today, the name Erasmus represents the EU student exchange programme (European Region Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students) encouraging students to study in another European country to get to know more cultures and become more European. One measure of its success is the birth of one million babies parented by Erasmus students since the scheme started in 1987.

Most students vaguely know Erasmus as the ‘humanist’ scholar who championed values of tolerance and freedom. Oh yes, and who also wrote that satire on church and society, In Praise of Folly.

Few, however, recognise him as a devout believer passionate about making the Bible accessible to all, urging princes, popes, kings and kaisers, as well as scholars, students, ploughboys and prostitutes, to follow the teachings of Jesus. For Erasmus was no humanist in the secular sense of excluding God and religion. Such ‘humanism’ didn’t exist in his day. The Christian Humanism of the Renaissance focused on Jesus the man, his teachings, relationships and suffering, rather than the rituals, pilgrimages and traditions of the Church developed over the centuries.

The Modern Devotion movement, spreading throughout Northern Europe from his native country of the Netherlands, stressed imitating Christ’s example. Hence the movement’s discipleship manual, The Imitation of Christ, by Thomas a Kempis, which the young Erasmus read in schools of the Brothers of the Common Life in both Deventer and Gouda. To live like Christ was to become truly human.

Ad fontes

As a Christian Humanist, Erasmus was concerned to return to the source of the Christian faith: Sed in primis ad fontes ipsos properandum, id est graecos et antiquos. (Above all, one must hasten to the sources themselves, that is, to the Greeks and ancients). Returning to the Gospels and Paul’s letters, as stressed by Geert Groote and other leaders of the Brothers, became a high priority for Erasmus.

His studies and lecturing took him to universities in Paris, Oxford, Leuven and Turin, then to Rome, Venice, back to England and finally to Basel and Freiburg. He wrote prolifically on many subjects. But his main passion was to produce a better Latin translation of the Bible than the official eleven-century-old Vulgate version by Church Father Jerome.

Consulting Greek manuscripts brought to the West after the fall of Constantinople, Erasmus persevered in translating the New Testament. A Greek New Testament had never been published before Novum Instrumentum came off Johannes Froben’s press on March 1, 1516, with Greek and Latin columns on each page.

Erasmus wrote: ‘I perceived that that teaching which is our salvation was to be had in a much purer and more lively form if sought at the fountain-head and drawn from the actual sources than from pools and runnels. And so I have revised the whole New Testament (as they call it) against the standard of the Greek original.’

All languages

For the fifty-year-old Erasmus, this was his opus magnum, a major step towards making the whole Bible accessible to all. In his preface he wrote: ‘I would that even the lowliest women read the Gospels and the Pauline epistles. And I would that they were translated into all languages so that they could be read and understood not only by Scots and Irish, but also by Turks and Saracens…Would that, as a result, the farmer sings some portion of them at the plow, the weaver hums some parts of them to the movement of his shuttle, the traveler lighten the weariness of the journey with stories of this kind!’

While Erasmus himself never translated into the vernacular languages of Europe, his vastly improved Latin and Greek translations directly triggered Luther’s German Bible in 1522, Tyndale’s English version in 1526, Lefèvre d’Étaples’ French translation in 1530, and later Dutch (1591) and Italian Bibles (1603). Most New Testament translations up until the 19th century were based on his work.

Erasmus changed the Vulgate’s rendering of Matthew 3:2—’be penitent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand’—into ‘repent,…’. Jerome’s translation had spawned the development of the Catholic doctrine of penance, and in turn the concept of indulgences, a practice opposed by both Erasmus and Luther.

Both men longed for the reform of the Church. While many said: ‘Erasmus laid the egg which Luther hatched’, Erasmus replied that the split-off Reformation Church was not the bird he had expected. That rupture, and all it would mean for the future, alarmed him.

For Luther and the Protestants, Erasmus remained too Catholic. For the Catholics, he was too Protestant. As we approach the 500th anniversary of the Reformation next year, he still has much to teach us.

Till next week,