The words ‘brew’ and ‘pray’ don’t really mix for people from my church background. Yet this past weekend, as honorarium for speaking at a open monastery day in the southern Netherlands, I was included in a ‘Brew and Pray’ day, mixing two centuries-old Benedictine traditions.

Perhaps it was God’s humour that a Baptist Kiwi should be asked to speak to Europeans in a monastery about the role of cloisters in shaping Europe’s identity. My church’s traditionally negative attitude towards both beer and monasteries probably developed on the one hand as a reaction to the abuse of drink among the working class in 19th century England, and on the other as a typically Protestant assumption that nothing much worth mentioning happened spiritually after Paul and before Luther.

As we approach the 500th anniversary of that great rupture we call the Reformation, we do well to ask, what positive elements did our Protestant forebears throw out with the bathwater?

Brewing is not actually what first comes to my mind. However, until relatively recently, drinking beer was far safer than drinking alternatives, including water. That’s why in the Dutch city of Utrecht, where there were 28 monasteries before the Reformation, there were also 24 breweries!

Significant role

Arthur Guinness, founder of the famous beer brand, was deeply influenced by the ministry of John Wesley and founded the first Sunday School in Ireland. His family motto was: Spes mea in deo (My hope is in God). Disturbed by widespread drunkenness, he believed God told him in prayer to ‘make a drink that will be good for men’. So he developed his dark stout beer containing so much iron that people felt full before they could drink too much. The alcohol level was lower than gin and whiskey. (Recent University of Wisconsin research has concluded that a pint of a Guinness a day actually bolstered health and was much better than the caffeine in coffee or high fructose corn syrup in soda.)

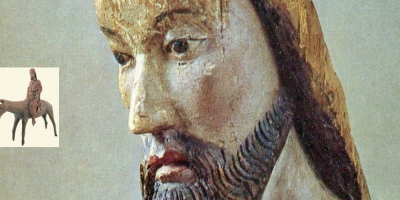

As I walked (ran?) my audience through twenty centuries of church history in less than an hour, I was reminding myself of the hugely significant role monastic communities played in developing Europe’s culture, society and cities; from the earliest desert communities, the Irish Celtic, Benedictine and Cistercian monasteries, the Franciscan and Dominican urban presence, to the houses of the Brothers of the Common Life in the Low Countries. They became the building blocks of the new order which emerged in Europe after the collapse of the Roman Empire. They modelled a lifestyle of covenant and commitment, based on the Great Commandment to love God and neighbour. They expressed the compassion and mercy Jesus spoke about in Matthew 25: to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, shelter the homeless, quench the thirsty, visit the prisoners and comfort the sick. They set up hospitals and guest houses for the sick, pilgrims and travellers, and provided the social welfare services in the emerging city states.

Rescuing civilisation

Combining prayer and work, ora et labora, they tamed wildernesses and drained swamps, built stone walls and dikes, created farms and gardens to bring order out of chaos, and taught the peasants to till the land and make it fruitful. They became the centres of education and scholarship, painstakingly copying and preserving the ancient manuscripts, rescuing civilisation from the onslaught of barbarianism and laying the foundations for the multiple Bible translations we now simply take for granted. They pioneered writing and styles of script, including our lower case letters, something the Romans never developed. Their scriptoria, libraries and books were to lead to the emergence of the first universities, staffed by scholar-monks and structured along monastic lines, reflected in the titles and gowns of professors and administrators in universities around the world today. The motto of Oxford University to this day is: Dominus Illuminatio Mea (The Lord is my light).

These communities became centres of art and music, as well as commerce and trade, bequeathing to the financial world the double-column entry system. (Hmm, was it the Franciscan Luca Pacioli in Milan in 1494, or Benedikt Kotruljević, in Dubrovnik, in 1458?) The father of the scientific method, Roger Bacon, was a Franciscan who transformed the methodology of experimental study, created the first scientific classification of nature, the elements and music, and whose study of light led to the invention of eyeglasses.

Not to mention the role of monasteries in the development of the beer and wine industries! Nor of their role in the expansion of the Christian faith as mission structures. For when Protestant rulers disestablished monasteries during the Reformation, sometimes overnight as in Amsterdam in 1578, they lost a powerful means of mission expansion for three whole centuries!

Perhaps this coming year we should take a humbler look at church history to see what else we have missed.

Till next week,