This past weekend 1700 years ago, a military battle took place just outside Rome the outcome of which profoundly shaped western history and still continues to influence our world. While not militarily strategic, the battle of Milvian Bridge led to consequences that for many seemed to be direct answer to prayer.

This past weekend 1700 years ago, a military battle took place just outside Rome the outcome of which profoundly shaped western history and still continues to influence our world. While not militarily strategic, the battle of Milvian Bridge led to consequences that for many seemed to be direct answer to prayer.

The early centuries of the church had seen intense periods of bloody persecution. While some church fathers saw martyrdom as a powerful witness (‘martyr’ means ‘witness’), and the ‘blood of the martyrs’ as ‘the seed of the church’, it was natural to pray for an end to the persecution. Many longed for a era of peace, the millennium, allowing the gospel to be spread without opposition.

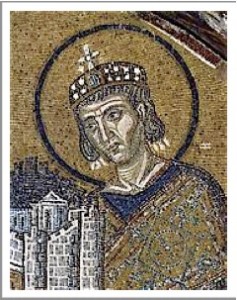

According to Eusebius, the first church historian, the battle of Milvian Bridge, in which Constantine defeated and killed his rival to the title of Roman emperor on 28 October 312, was an occasion of divine intervention in history.

The son of the western emperor Constantius (one of four co-emperors), Constantine was proclaimed as Augustus by his own troops in York when his father died in July 306. But this was not universally recognised across the empire. After several years of jockeying among the four contenders for supreme power, Constantine moved on Rome with his army of 100,000 soldiers to confront his brother-in-law, Maxentius.

Sign

They met on opposite sides of the Tiber River, just north of Rome. According to Eusebius, the battle marked the beginning of Constantine's conversion to Christianity. For there, he wrote, Constantine had a vision of God promising victory if he fought under the sign of the Chi-Rho, the first two letters of Christ's name in Greek. Constantine, the story goes, heard the words IN HOC SIGNO ERIS, meaning, In this sign you will conquer.

The battle ended in complete victory for Constantine after the bridge collapsed as the opposing army tried to retreat, tossing the soldiers in full armour into the river. Maxentius himself drowned, leaving the road to Rome open for the victorious Constantine to assume full imperial authority.

Eusebius and official church historians ever since have hailed this moment as one of the most significant turning points in church history.

Indeed, for many contemporary believers, it seemed as if the millennium had arrived! For the very next year, Constantine declared Christianity to be an official religion of the empire, with the Edict of Milan. Later it became the official religion. Nothing else would be tolerated! What an amazing turn-around!

Constantine’s decisive victory, the official line goes, led directly to the evangelization of the entire empire, and shaped a Europe which, over time, “gave rise to the values of human dignity, distinction and cooperation between religion and the state, and freedom of conscience, religion and worship.”

Definitions

To mark this 1700th anniversary, the Vatican has organised symposia with titles including: "Constantine the Great. The Roots of Europe". The Roman Catholic Church of course dates its official rise to power in the empire to Constantine’s conversion Whatever we think about the man, we cannot deny that his accession to the throne and the decisions he made profoundly shaped subsequent European history. He introduced laws abolishing crucifixion and Sunday trading, and made Easter an imperial celebration. He built the first St Peter's in Rome. He built a new eastern capital, modestly named Constantinople, resulting in a bi-polar Europe that exists till today. The fault-line between former Latin- and Greek-speaking halves helped define the First World War, the Cold War and the more recent Balkan Wars.

However, almost immediately after Constantine embraced the Christian faith, the definitions of ‘Christian’ and ‘church’ changed. It was no longer costly to declare oneself Christian; it was now fashionable, much like what happened in Russia 20 years ago when communism collapsed. Standards of spirituality dropped. The church soon became a powerful and rich institution, the ‘spiritual’ mirror of the empire.

Many seeking a purer faith joined communities in the desert, producing the monastic movement. Such communities based on covenant became the building blocks of the society that emerged after Rome’s collapse. They were the chief means through which Europe was evangelised. So even by provoking this reaction, Constantine’s ‘conversion’, however genuine it may or may not have been, had profound implications for Europe.

Constantine remains one of the most controversial yet significant figures in European history. It’s worth pausing to remember the impact of these events 1700 years ago.

Till next week.

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,