The Reformation, triggered 500 years ago next week by Martin Luther’s publication of objections to practices of his own Roman Catholic Church, is being commemorated in surprising places.

In Budapest, capital of a predominantly Catholic Hungary, 95 square-shaped concrete tablets representing Luther’s 95 Theses have been laid in Calvin Square, each featuring a pair of quotes from Reformers and prominent Hungarian authors.

On a visit to the city this past weekend, I also encountered large colour posters in bus shelters and metro stations announcing performances by the Hungarian State Opera telling the story of the Huguenots and the French Reformation.

Last month in the heart of traditionally-Orthodox Kyiv, a gathering of Protestant Ukrainians in Maidan Square, planned for about 5000, snowballed into a huge crowd including many non-believers. Estimates varied from 160,000 and 500,000 strong. President Petro Poroshenko had earlier signed an order to recognise the anniversary of the Reformation, to recognise ‘the enormous contribution of Protestant churches and religious organizations … and to express respect for their role in Ukrainian history.’

Some observe that Ukrainian officials are seeking outside their own tradition for the spiritual resources to help them reform the country. Fearing Russian Orthodoxy will only ‘pull the country backwards’, they have become aware of the Reformation’s influence on all of society, culture, economics and politics.

Ratings

For the Reformation led to profound changes in the societies where it took root, a fact largely forgotten or ignored in western nations. The long term effect can be seen in charts of global ratings measuring the strength of democracy, corruption and Gross National Product.

A click on each of these links will reveal a consistent pattern. Allowing for the distortion of oil-rich economies and off-shore banking havens in the GNP ratings, nations with Protestant backgrounds typically top the ranks, followed by Catholic and then Orthodox societies. Buddhist, Hindu, Moslem and animist societies lag well behind. Japan and Singapore are ‘exceptions that prove the rule’, having had strong American and British influence shaping their social institutions respectively.

Some would say that the high ranking of the Protestant-background nations is due to the ‘emancipation from religion’, i.e. secularisation, which first emerged in those nations. Indeed, the Reformation did produce the factors giving rise to secularism, for reasons we cannot explore here. Yet Harvard historian Niall Ferguson once lamented in the NY Times that ‘the stunning triumph of secularisation in Western Europe’ had produced a decline of the Protestant work ethic in Europe.

On the 500th anniversary of the start of this world-shaping movement, we should pause to ask what causal links can be demonstrated between the Reformation and economic growth, democratic stability, and social justice in Protestant-background countries. Would Ukraine’s leaders be wise to look to Protestant spiritual resources as they seek to move their nation into the future?

Firstly, the Reformation opened the path to freedom of religion, of conscience and of expression. Religious freedom reduces corruption once religious monopolies are broken. Encouraging tolerance and respect, it reduces conflict in society. Civil and human rights are promoted under conditions of religious freedom. Freedom of conscience also led to the value of the individual. The emphasis on each individual accepting responsibility for one’s own spiritual welfare contributed significantly to the development of human rights.

Entrepreneurship

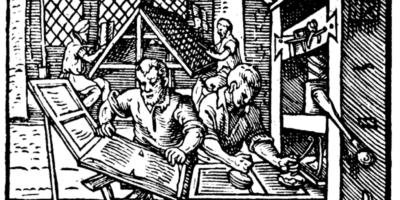

Secondly, the emphasis on reading the Bible daily led to literacy and better education. That in turn increased labour productivity, fostered technological innovation and economic improvement. Max Weber’s thesis that Protestants were generally more diligent in their work is often quoted as explaining the economic success of Protestant-influenced countries. Understanding work as worship, as Luther stated, gave Protestants higher motivation in their work productivity, and encouraged a spirit of entrepreneurship.

Thirdly, the recovery of the concept of the priesthood of all believers undermined traditional hierarchies and produced a stronger civil society. Alexis de Tocqueville used the phrase ‘the art of association’ to describe the Protestant America he observed almost two centuries ago where a strong spirit of voluntary cooperation has continued to shape community life.

Wherever the Reformation took hold, governmental structures were radically altered and contributed to the emergence of representative parliamentary government. In Geneva, where John Calvin replaced ecclesiastical hierarchy with elected elders, it was soon realised that what was good for the church was good for the state. The Geneva model was eventually adopted in Britain, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States, which in turn became models for democratic governments formed worldwide.

Yes, the Reformation also had its darker side, which we may address in a future blog. But politicians in Ukraine, and for that matter anywhere, should reflect seriously on the evidence of the charts linked above.

Till next week,