France has become the latest and biggest European country so far to adopt the ‘Nordic Model’ of combating prostitution by criminalising clients rather than prostitutes. While the controversial legislation took over two years to pass through parliament, the final vote earlier this month was overwhelmingly in favour: 64 for, 12 against, 11 abstentions.

Next to fines of up to €3750, offenders would have to attend courses describing the conditions under which prostitutes work. French Socialist MP Maud Olivier, who sponsored the legislation, said that 85% of prostitutes in France were victims of trafficking.

Sweden, in 1999, was the first country to criminalise clients rather than the prostitutes. After street prostitution dropped to half previous levels, Norway (2008) and Iceland (2009) followed their Nordic neighbour. In 2014, Northern Ireland became the first British country to adopt this model.

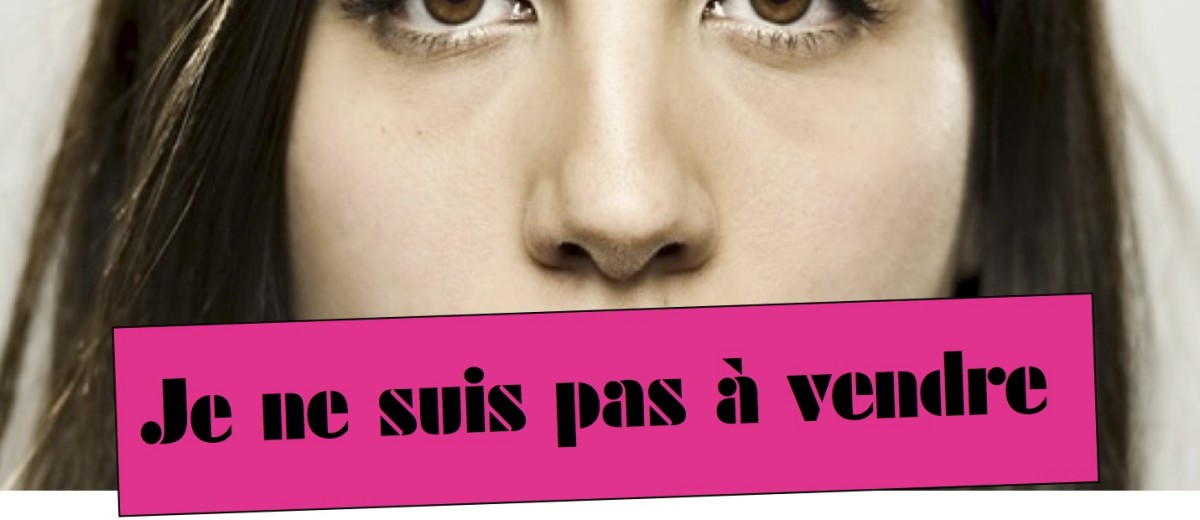

The new French law is in line with a 2014 European Parliament resolution calling on EU countries to reduce the demand for prostitution by punishing the clients. Prostitution violated human dignity and human rights, the resolution stated. It called on member states to find exit strategies and alternative sources of income for women who wanted to leave prostitution.

Mary Honeyball, the British Labour MEP who drafted the resolution, argued that legalisation of prostitution had been disastrous in the Netherlands and Germany. A more nuanced approach was needed, punishing men who treated women’s bodies as a commodity, without criminalising those driven into sex work. She called for ‘a strong signal that the European Parliament is ambitious enough to tackle prostitution head on, rather than accepting it as a fact of life.’

The Nordic Model recognised the connection between the prostitution market and sex trafficking. Demand for sexual services fueled sex trafficking; shrinking the market for prostitution reduced sex trafficking. A recent study of 150 countries, published by the London School of Economics, showed how legalized prostitution led to expansion of the prostitution market and increased human trafficking.

Pros and cons

Understandably the sex industry feels threatened. On the streets and in the media, sex workers and lobbyists claimed that the legislation made sex work more dangerous. One prostitute demonstrated with the banner, ‘Don’t liberate me, I’ll take care of myself’.

Maud Olivier anticipated this argument by asking parliament: ‘Is it enough for one prostitute to say she is free for the enslavement of others to be respectable and acceptable?’

Others argue that criminalising clients diminishes the likelihood of them reporting concerns about a sex worker’s well-being, and that sex workers have to risk more to protect buyers from prosecution. Prostitution will be pushed underground, they claim.

Scanning through media reports on the new French legislation, I read experts arguing various pros and cons in an apparent attempt at journalistic even-handedness. Yet I found no journalists asking what the Swedes would say after more than sixteen years of experience.

Kajsa Wahlberg, Sweden’s rapporteur on anti-human trafficking activities, has no doubts about the success of their model. Prostitution and trafficking has been reduced significantly. Violence to prostitutes has not increased. Nor has prostitution moved underground.

At a 2010 conference in The Hague, Wahlberg told Dutch officials that a Special Inquiry on the decade-long results of the legislation reported no evidence of increased violence or underground prostitution. Between 1998 and 2003, the number of prostitutes in the country dropped 40%. Male Swedish clients had dropped from 13.6 % in 1996 to only 7.8% in 2008.

Bad market

‘We don’t have a problem with prostitutes. We have a problem with men who buy sex,’ said Wahlberg. Without men who wish to purchase a sexual service, the prostitution industry and its networks could and would not continue to operate. The market would be closed down.

Wahlberg: ‘Criminals are businessmen; they calculate profits, marketing factors and risks of getting caught before investing time and money into selling women in a particular place. Our job is to do everything possible to create a bad market for traffickers. Prostitution activities are not and cannot be pushed underground. The profit of traffickers, procurers and other prostitution operators is obviously dependent on easy access for men to women.’

From wire-tapped conversations of organized crime networks, she added, police knew that these networks saw Sweden as a bad market, preferring countries where prostitution was legalized or tolerated.

Wahlberg told her audience in The Hague: ‘We want to create a society where the human rights of all women and girls are protected. I want to encourage other countries to follow suit–because then we will end the trafficking in human beings for sexual purposes.’

This is not just a task for police and politicians. At the State of Europe Forum in Amsterdam next month, Jennifer Tunehag of the European Freedom Network (EFN) will lead a workshop on trafficking in Europe today and what we in our churches and organisations can do to help end this modern slavery.

Till next week,