Germany and France have done it. So have Belgium and Britain. And even the United States. Amsterdam did it this week. But the Netherlands? Not yet.

Saying sorry is something we all have to learn. Teaching children to say that word requires patience. Coaxing national governments to do the right thing can be like urging stubborn children who invent all sorts of excuses to avoid that word.

This week, on the anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Surinam in 1863, the mayor of Amsterdam, Femke Halsema, officially apologised for her city’s two centuries of active engagement in the slave trade.

‘On behalf of the city’s administration, I apologise for the active involvement of the Amsterdam city council in the commercial system of colonial slavery and the worldwide trade in enslaved people,’ Amsterdam’s first female mayor told the crowd gathered in a city park on the annual Keti Koti (broken chains) ceremony commemorating the end of slavery. ‘It is time to embed the great injustice of colonial slavery into the identity of our city, through broad and unconditional recognition.’

Golden?

Used to basking in the glory of the Golden Age of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when Amsterdam was the world’s richest and most powerful city, Amsterdammers are now becoming more aware of the dark side of their city’s past prosperity. The Rijksmuseum, for example, no longer uses the term ‘Golden Age’.

A decade ago, Amsterdam’s 400-year old unique canal district was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site with its grandiose mansions built by prosperous city merchants. Amsterdam was once the world’s ‘central warehouse’ where merchandise from all over the world was stored, traded and distributed.

Yet the shadow side is that such luxurious mansions were built on human trafficking. The canal district was home to many slave traders: city fathers and administrators, who doubled as directors of the West Indies Company (WIC), the East Indies Company (VOC) or of the Surinam Society. All of Halsema’s mayoral predecessors in that period were engaged in the slave business, as Amsterdam was co-owner of the Surinam Society with the WIC. At its height in the 1770s, slavery generated over 10% of the gross domestic product of the province of Holland and about 5% of the national GDP.

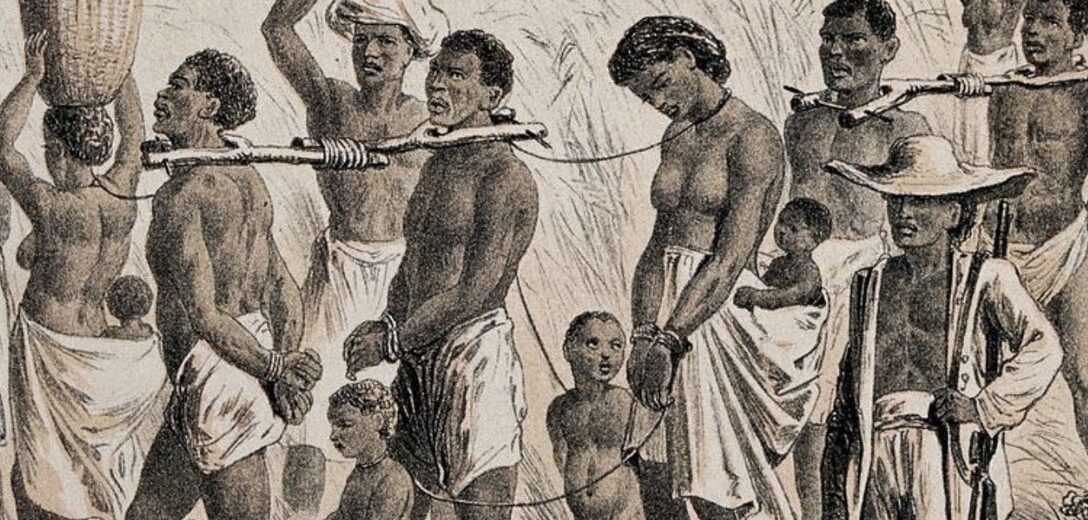

Some 600,000 slaves were transported like animals on Dutch ships to the Americas from west Africa. They suffered inhumanly crowded conditions of heat and excrement, many dying during the one to three month voyage. Those who survived were branded with logo of the WIC. When emancipation finally came in 1863, the slave owners, businesses and banking institutes were generously compensated for – yet not a cent for the slaves.

Amsterdam’s apology this week followed the earlier example of London and Liverpool, which Rotterdam, Utrecht and The Hague are each seriously considering to imitate. Last year the ChristenUnie and another coalition party last year pushed for a national apology.

But prime minister Mark Rutte – who is unmarried and has never had to teach his children to say sorry – sees no point in apologising. His excuse is that it risks polarising the Dutch population. The unspoken fear is of opening a Pandora’s box to demands for more compensation, echoing Amsterdam’s resistance to the original emancipation based on financial considerations,

Suffering

This despite a report from a commission set up by the home affairs ministry advising that the Netherlands apologise for its slavery past, and recognise slavery and the slave trade as crimes against humanity. As the legal successor to the former Netherlands, it is up to the current cabinet to apologise for ‘directly or indirectly allowing’ slavery and the slave trade, the report read. ‘It is not about designating individuals as guilty, but about recognition by the state of the Netherlands of the suffering caused by slavery.’

Further recommendations from the report were for an annual national day of remembrance on July 1, the day when slavery was abolished in 1863, the establishment of a national museum of slavery and that the country’s slavery past be taught more comprehensively in schools.

Rutte however still has the support of a small majority of the Dutch population who argue that today’s generation cannot be held responsible for the wrongs of past generations. Yet others point out that apologies have been offered for Dutch assistance to the Nazis in the Holocaust, and for the excess and violence of Dutch soldiers during Indonesia’s war of independence. Without saying sorry, they stress, the roots of racism and discrimination will not properly be addressed.

Meanwhile, to create more consciousness of this black page of Dutch history, the city is offering a free book on Amsterdam’s slavery past, while the Rijksmuseum is hosting a major exhibition on slavery.

The Netherlands was one of the last western nations to abolish slavery. Sadly, it will be one of the last to say sorry.

Till next week,