The New Year is the time for making resolutions and setting goals. So, here’s my first resolution, which in turn will lead to goals for the coming year… and years to come.

Sitting on my desk has been a business card of an elder of an evangelical church where I sometimes speak. He first wrote to me with a question over a year ago. I have always intended to respond to his question, but two Christmases have now gone by…

So, its high time for a response to his query, as follows:

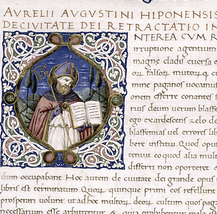

Augustine argues in Civitate Dei (City of God), as consolation for the fall of Rome, that we await a heavenly, spiritual kingdom, not an earthly, worldly one. Jesus also said: my Kingdom is not of this world.

Augustine argues in Civitate Dei (City of God), as consolation for the fall of Rome, that we await a heavenly, spiritual kingdom, not an earthly, worldly one. Jesus also said: my Kingdom is not of this world.

The realisation of Kingdom values in this world’s politics is a question that concerns the validity of Christian politics. Is the Kingdom of God present when her principles of righteousness are implemented in society, even if the King is not himself recognised?

Jesus gave hope: ‘the Kingdom is near’. But he also gave conditions: ‘repent!’

Did not the Kingdom of God in power begin with a recognised King? Was not Daniel’s message that the kingdom of his exile would be replaced by Jesus’ Kingdom?

Jesus did not speak out about the political situation of his own time, the Roman Empire, did he?

Such thoughts strongly dictate the views of many (evangelical) Christians about Europe today. What is your answer to these ideas?

These questions deserve more space than the rest of this page offers, of course! But let me try to sketch a response.

Paradox

Augustine wrote to correct the idea many believers of his time had, that once Constantine had embraced Christianity a hundred years earlier, the Millennium was being ushered in and with it the Kingdom. Constantine had seemed to many a wonderful answer to prayer. The persecution had stopped and God’s Kingdom and the Roman Empire now went hand in glove.

Until the Barbarians appeared at the gates of Rome, that is. Now Augustine wrote to warn against the idea that God’s Kingdom would come like a worldly empire, fully present on earth.

It is one extreme to say that the Kingdom is all present. Yet it is another to say it is all future. The paradox of the Kingdom is that it is ‘already…but not yet’. Jesus not only said the Kingdom was near, but that it was here! He spoke of the Kingdom advancing forcefully already in his day (Mt 11:12). He told John the Baptist’s disciples to look at the signs as evidence that the Kingdom was coming.

But he also said his kingdom was not of this world, implying that it embodied different values. It could not be advanced purely by worldy means, by military conquest for example.

True, Jesus never took on the Roman Empire directly, but he did confront the local political powers. The soft powers of his Kingdom were truth and love, powers which did eventually win over Rome…and the Barbarians.

The Bible Jesus read was the Old Testament. And there is much about politics in that part of the Bible: about principles of nationhood with Moses and statehood under Samuel. Joseph, Daniel, Nehemiah and Esther are all examples of God’s agents in politics. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks calls the Bible ‘a forgotten political classic’. The 17th century European fathers of freedom and democracy–Milton, Hobbes, Locke and the Pilgrim Fathers–were in dialogue not with Aristotle’s Republic or Plato’s Politics, he writes, but with the Hebrew Bible. Hobbes quoted it 657 times in one book alone! ‘We have forgotten how significant the Bible was in shaping the idea of a free society at the birth of modernity,’ writes Sacks.

The Bible gives us the vision of human dignity on which our concept of human rights is based. It champions freedom from evil, tyranny and slavery. It has inspired Western civilisation’s meta-narrative of hope. And it espouses a view of limited politics, differentiating between society and the state; where areas of society are none of the state’s business–unlike the Greek view in which the people served the state.

Paul in the New Testament writes about the believer’s attitude to government and calls rulers (including pagan Roman emperors) ‘God’s deacons’ (Roms 13:4); an echo of Isaiah’s reference to the pagan King Cyrus as God’s ‘shepherd’. (Is. 44:28)

The Bible is more political than we sometimes realise.

On Earth

What did Jesus mean by ‘the Kingdom’, and what would that look like? It was his main topic of teaching and preaching, mentioned well over 100 times in John’s gospel alone–unlike ‘the church’ which is mentioned only in two verses in all the gospels! The best definition comes from the Lord’s Prayer: ‘May your Kingdom come, (in other words) may your will be done…’

So where God’s will is being done, whether people are aware of it or not, whether the King is recognised or not, his Kingdom is coming in some measure. That may be in our schools, businesses, parliaments, homes, churches, clubs, streets, public squares, universities–you name it! Where is it to come, according to this prayer? ‘…on earth–in Europe–as it is in heaven’!

Yes, the coming of the Kingdom demands repentance. Britain repented from its slave trade under Wilberforce’s influence. Men and women were freed and the Kingdom advanced in some degree throughout the British Empire.

Repentance is turning away from evil to do what is right. Our responsibility as God’s people is to be salt and light in our societies, urging ourselves and others to do God’s will in every sphere of life. We are to proclaim the good news of the Kingdom, seek His Kingdom first, and pray for his Kingdom to come… in Europe and everywhere else on earth.

That should keep us busy in 2011–and for the rest of our lives!

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,