With the approach of Easter, concert halls, cathedrals and churches all across Europe have been resonating with the genius of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St Matthew Passion, often considered the greatest musical work ever composed.

Last Wednesday, March 21, Bach’s birthday was celebrated by radio programmes the world over (‘Happy Bach Day’) and by thousands of musicians playing Bach freely in public spaces.

Bach wrote no less than five Passions, but only those based on St Matthew and St John have survived. The Passions belonged to a centuries-old tradition of chanting the Gospel accounts of Christ’s final suffering and death, recorded as early as the fourth century.

Just as the Gospels themselves are Passion narratives with extended introductions, Bach’s Passions are part of a series of cantatas, which in turn belong to the yearly cycle of church music. Following Luther’s declaration, ‘The cross only is our theology’, Bach’s music made the cross central.

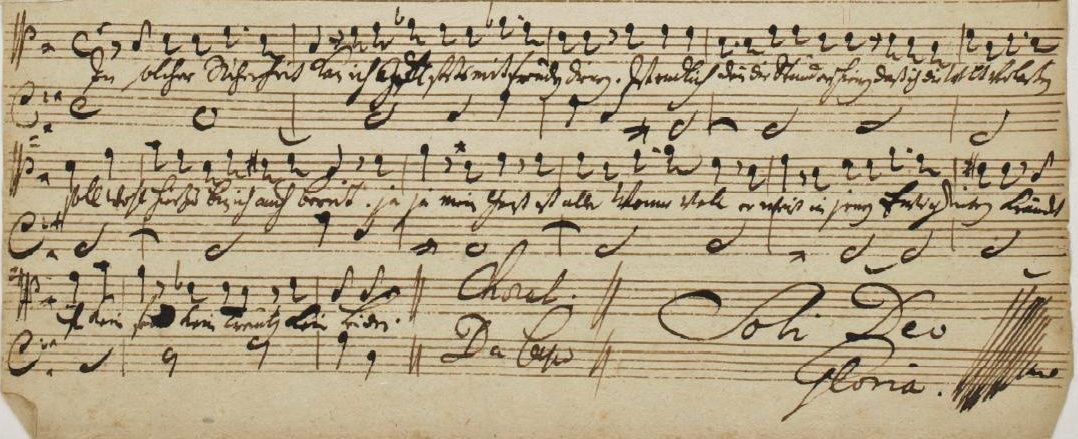

From his handwritten manuscripts, it is clear how much Bach personally believed in the Gospel. He often wrote abbreviations on his musical scores such as ‘S.D.G.’ (Soli Deo Gloria – Glory to the only God), ‘J.J.’ (Jesu Juban – Help me Jesus), ‘I.N.J.’ (In Nomine Jesu – In the name of Jesus). He urged his pupils to commit their talents to the Lord Jesus Christ in order to become great musicians. Music, he believed, was an act of worship.

His library contained over eighty books on the Christian faith, including many of Luther’s writings. Clearly his personal faith was the source of inspiration for his almost superhuman and unparalleled musical achievements.

Bach is held to be the father of classical music. His development of the fugue – and thus contrapuntal music – led to concertos, sonatas, quartets and symphonies. His teaching notebooks and violin books became the basis for music theory and practice ever since. He pioneered the use of all five fingers on the keyboard, including the thumb. The Baroque era of music climaxed in Bach’s work and laid the foundation for all music that followed. He profoundly influenced the works of others including Beethoven, Haydn, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Chopin, Wagner and Brahms.

Inspiration

It is impossible to think of the development of western music without Johann Sebastian Bach, and, even more so, without the profound influence of the Bible and the story of Jesus Christ. Why did western music develop so differently from that of other cultures?

While Greek and Roman cultures have helped shape western art, literature and drama, we know little about their music. Jewish worship music however was the inspiration of early Christian music. The Bible contains many descriptions of the use of music in worship in both Old and New Testaments. The Psalms are a collection of worship songs often with instructions to the director of music, even designating the tune (e.g. Psalm 75).

The Psalms directly inspired the liturgy of the early church and the emergence of Gregorian music in the Middle Ages. It was an eleventh-century Benedictine monk, Guido of Arezzo, who invented musical notation using a four-line staff on which to write the pitch of the note. This enabled music to be recorded and passed on without depending on human memory. This one invention was as crucial to the development of music as writing was to literature. To help his students memorise the notes of the scale, c-d-e-f-g-a, Guido gave the notes names from the first syllables of the phrases of a Christian song focused on St John, as follows:

UT queant laxis REsonare fibris MIre gestorum FAmuli tuorum SOlve pollutis LAbiis reatum Sancte Iohannes.

Here is the origin of the ‘do-re-mi’ song made famous by the Von Trapp family of The Sound of Music film. Over time DO replaced UT and TI was added after LA.

Harmony

Notation freed western music to develop with written scores, order, logic and rules. Polyphony (different melodies playing simultaneously) and harmony led to new expressions and new techniques in church music. Choirmasters at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris pioneered further developments in musical notation of rhythm as well as pitch. The motet (from the French ‘mot’ for ‘word’) spread throughout Europe in the thirteenth century, introducing four-part harmony – soprano, alto, tenor and bass.

While secular music began to flourish in the following centuries, the foundations had been shaped by church music. Gutenberg’s invention of the moveable type printing press not only enabled widespread distribution of the Bible. It also made musical scores more readily accessible. It helped spread Luther’s teachings and catalyse the Reformation in which music was to play a central role.

Asking ‘Why should the devil have all the good music?’, Luther adapted popular drinking songs to teach basic Christian doctrines. Two centuries later, much of Bach’s work involved setting Luther’s Bible translation to music; most notably the St Matthew Passion, which by taking chapters 27 and 28 of the first gospel is retelling the story of Jesus’ death and resurrection to millions this week.

Till next week,