As we approach Easter, one of the greatest musical works ever composed will be performed by countless choirs and orchestras to sold-out audiences in churches and concert halls across Europe.

As we approach Easter, one of the greatest musical works ever composed will be performed by countless choirs and orchestras to sold-out audiences in churches and concert halls across Europe.

For the performance of Johan Sebastian Bach’s St Matthew’s Passion is one of the highlights of the European social calendar. In Holland, for example, leading members of the political establishment will converge on the historic town of Naarden, outside Amsterdam, and file into the St Jans Basilica for the traditional event under its magnificent painted barrel ceiling depicting corresponding scenes from Old and New Testaments.

In Bath, England, a traditional Good Friday performance always followed the Palm Sunday rendition by the Old Bach Society in London enabling the choir to travel westward for a repeat concert.

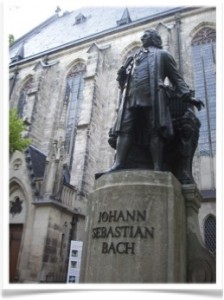

But to experience something of the original impact of this unsurpassed musical liturgy, St Thomas’ Church in Leipzig is the place to be. One Dutch visitor who witnessed the event there last year said that although he had heard the Matthëus Passion some sixty times in his life, the Leipzig concert was the most beautiful musical experience of his life.

On Good Friday, 1727, the St Matthew’s Passion was performed by Bach for the first time in the Thomaskirche. Bach was city director of choral music (meaning he was responsible for the weekly music in the services of Leipzig’s four main churches), as well as being cantor of the Thomas School for boys (meaning giving singing and music lessons to over 50 boys).

Unparalleled

Bach composed a new cantata for every Sunday, to be sung alternatively in the churches of St Thomas and St Nicholas, and for each feast day, around sixty a year! He wrote five yearly cycles, making some 300 cantatas, of which some 200 still exist. Other Baroque composers may have written more, but Bach’s work was unparalleled in depth, subtlety and theological richness expressed in the counterpoint of text and music.

Of four, maybe five, Passions written by Bach, only St Matthew’s and St John’s remain, each with different theological emphasis. They were all part of the annual cycle of cantatas, rather than stand-alone pieces. As the Passion narrative in the Gospels are part of the whole story of Christ’s life on earth, so too Bach’s Passions belong to a bigger picture. Yet for Bach, as for Luther and for Paul (We preach Christ crucified–I Cor. 1.23), the cross was at the centre of the gospel story.

Descriptions of chants of the Passion story during Holy Week go back to the 4th century. The practice of chanting the whole story from one of the gospels developed throughout Christendom in the Middle Ages. During the Renaissance, harmonisations were introduced. Luther, asking why the devil should have all the good music, encouraged the narratives to be put to music. In the 17th century, musical settings expanded to include poetic verses called ‘madrigal’ texts, under the influence of operatic styles.

While following this tradition, Bach however anchored his texts to the Bible as he put Matthew’s version of the Passion story to music with two antiphonal choirs, a third boy soprano choir, two orchestras and even two organs, as well as the soloists of the main characters.

To enthralled audiences throughout Europe every year, Bach continues to urge all who hear to consider the guiltless Lamb of God who died out of love for us, the guilty. St Matthew’s Passion is a reminder of the profound impact firstly of the ‘greatest story ever told’ and of how deeply embedded this story remains in European culture, despite secularism’s inroads.

Luther’s shadow

Bach’s link with Luther began the moment he was born in Eisenach, literally under the shadow of Wartburg Castle, where Luther translated the German New Testament while in hiding. Bach attended the same school as Luther in Eisenach, and grew up schooled in the Reformer’s theology. Bach’s cantatas are described as musical sermons based on Luther’s theology, encouraging appropriate responses.

This summer again, as part of our Summer School for European Studies, we visit the Wartburg, Eisenach, Leipzig and many other places where we see the impact of ‘the greatest story ever told’ on art, music, language, literature, education, family, science, politics… You could still join us. (see www.schumancentre.eu/sses)

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,