A stone’s throw from the apartment where we stayed during a conference last week in the heart of the beautiful French city of Lyon was a street once ominously called Rue Maudicte, ‘street of the accursed’.

A stone’s throw from the apartment where we stayed during a conference last week in the heart of the beautiful French city of Lyon was a street once ominously called Rue Maudicte, ‘street of the accursed’.

Since renamed, this was the street where a wealthy merchant named Peter Waldo had lived in the twelfth century before his expulsion from the city following his radical conversion and equally radical ministry.

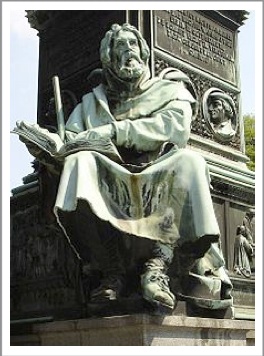

Waldo, active a generation before Saint Francis, could be called a grandfather of the Reformation. He has a place of honour on the Monument to the Reformers in Worms, Germany, where Luther was tried more than three centuries later (see photo).

For Waldo fathered a movement that was forced by persecution to spread across much of Europe, scattering seeds of reform that were in time to sprout into the Reformation itself. Today the followers of ‘Valdensius’ form the oldest non-Catholic religious body in Italy, the Waldensian Church in Piedmont.

Most of what we know is gleaned from Inquisition records telling us about a movement called the Poor of Lyon which emerged around the year 1170. The leader was a clothier and merchant, a man of some learning, ‘by the name of Valdensius or Valdensis after whom his followers took their name’.

Presumption

‘Infatuated with himself,’ so the Inquisitors reported, ‘he usurped the prerogatives of the Apostles by presuming to preach the Gospel in the streets, where he made many disciples, and involving them, both men and women, in a like presumption by sending them out, in turn to preach. These people, ignorant and illiterate, went about through the towns, entering houses and even churches, spreading many errors about.’

Because of this ‘presumptuous appropriation of a task which did not pertain to them,’ went the report, ‘they were excommunicated and expelled from their country.’

Waldo seems to have held a prominent position in the city before several events combined to bring him to renounce his lavish lifestyle and wealth. A friend’s sudden death at a banquet confronted him with ultimate reality: was he ready to face eternity? Seeking advice from a theologian friend at the cathedral, he was struck by Jesus’ instruction to the rich young ruler in Matthew’s gospel to sell all his goods and give the poor.

Waldo’s response was wholehearted. To the scoffers who gathered at his house as he distributed his possessions, he said, ‘Citizens and friends, I am not out of my mind, as you seem to think. This act I do for myself and for you: for me, so that if from now on I possess anything you may indeed call me a fool; for you, in order that you too may be led to put your hope in God and not in riches.’

Modelling their lifestyle on the early Christians, Waldo and his followers drawn from all sectors of society, including priests and scholars, committed themselves to lay preaching, voluntary poverty and faithful adherence to the Bible. Before giving all his wealth away, Waldo commissioned a translation of the New Testament into the local Franco-Provençal language, the first such translation in a vernacular language other than Latin.

Rather than set up a new religious order, the Waldensians saw themselves as a lay society, a community of men and women living in society and carrying out their vocation in the city.

Expulsion

At first the pope welcomed a Waldensian delegation to Rome in 1179, even accepting a copy of their translated New Testament. The welcome soon cooled however with the Third Lateran Council that same year. Unable to control the lay activities of the Poor, the local church leadership expelled them from Lyon.

They first relocated in Languedoc in southern France, where by 1184, they were branded as self-taught babblers, drifters, spongers and imposters, and then excommunicated.

Crusades against ‘heresy’ resulting from the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 eventually pushed the Waldensians out of southern France. Many crossed the Alps into Lombardy of northern Italy where they found like-minded dissidents and settled in communities of the Poor, which centuries later connected with Calvin’s Reformation in Geneva.

Yet others pushed on into central and northern Europe, to Switzerland, Bavaria, Brandenburg, Erfurt, Austria, Bohemia and Hungary, reaching Poland and Flanders in the north. Often itinerating as peddler and traders, they shared everywhere their most precious ware, the Gospel, and seeded these regions with the ideas of the Reformation.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,